Evaluation of the Intelligence Collection and Analysis Program: Introduction and part 1 findings

Acronyms and abbreviations

- AOC

- Agency Operations Committee

- BLMB

- Business Line Management Board

- BSO

- Border services officer

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CAS

- Corporate Administrative System

- CHS

- Confidential Human Source

- CPC

- Canadian Police College

- CSIS

- Canadian Security Intelligence Service

- DND

- Department of National Defence

- FINTRAC

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- FMM

- Functional Management Model

- FTE

- Full time equivalent

- GTA

- Greater Toronto Area

- HRB

- Human Resources Branch

- HQ

- Headquarters

- IA

- Intelligence analyst

- ICAP

- Intelligence Collection, Analysis and Production

- ICES

- Integrated Customs Enforcement System

- IID

- Intelligence and Investigations Directorate

- ILO

- International liaison officer

- IO

- Intelligence officer

- I&E

- Intelligence and Enforcement Branch

- ITPS

- Intelligence Targeting Policy and Support

- JFO

- Joint Force Operations

- KPI

- Key performance indicator

- LEA

- Law enforcement agencies

- MOU

- Memorandum of understanding

- NDC

- National Document Centre

- NTC

- National Targeting Centre

- NTS

- National Training Standard

- ORS

- Occurrence Reporting System

- PCO

- Privy Council Office

- PMEC

- Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee

- PMF

- Performance Measurement Framework

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- RDG

- Regional director general

- SCIDA

- Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act

- SOR

- Southern Ontario Region

- TBML

- Trade based money laundering

- VP

- Vice-President

Executive summary

The evaluation examined the relevance and performance (effectiveness and efficiency) of the Intelligence Collection and Analysis Program ("the program") from 2016 to 2017 to 2020 to 2021; in accordance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results. The scope of the evaluation was approved by the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee (PMEC) on . The evaluation was undertaken between and . While the National Targeting Centre (NTC) is an important part of the intelligence function of the agency, its processes were not evaluated because targeting has been identified for an upcoming standalone evaluation.

Program description

The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA or "the agency") facilitates legitimate travel and trade across the border while identifying and mitigating safety and security threats. The program governs the intelligence function across the agency and develops tools for frontline officers to assist in identifying people, goods, shipments and conveyances that may be inadmissible or pose a risk to the safety and security of Canada. The program collects information and develops intelligence products via multiple channels.

Intelligence products (tactical, operational and strategic), as well as the intelligence partnerships in which the agency engages, are intended to drive immediate, intermediate, and ultimate program outcomes as per the program's logic model (Annex B).

Evaluation methodology

Data collection and analysis for this evaluation were conducted between June and ; both qualitative and quantitative research methods were used. The evaluation team conducted interviews with key stakeholders within the agency; reviewed key documentation; performed benchmarking of performance measurement approaches of intelligence activities through a review of national and international literature; reviewed operational, performance, human resources and financial data; and obtained the views of external law enforcement partners (both domestic and international) through questionnaires.

Significant data limitations were faced in the course of this evaluation, as detailed in the findings below.

Evaluation findings

Relevance

The activities undertaken by the program were found to be relevant to agency operations and conducted within the CBSA's legislative parameters and mandate. The CBSA has legislative authority for intelligence collection. In areas where the CBSA does not have legislative authority (e.g., terrorism or organized crime), it assists other law enforcement agencies in such investigations by providing intelligence support where a border nexus exists.

While program activities are aligned with Government of Canada and CBSA priorities, the evaluation identified an opportunity to explore better alignment of intelligence activities to other business line priorities within the agency. The CBSA intelligence branch and its external partners perform complementary work while respecting the scope of their own mandates.

Effectiveness

The program's performance measurement and data challenges hindered meaningful reporting on program outputs and outcomes, and thus its effectiveness. The program has not yet implemented a Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) due to the challenges associated with measuring the outcomes of intelligence activities, as experienced by other similar intelligence organizations. Data limitations were also encountered and prevented an assessment of the program's impacts on preventing fraudulent immigration, human smuggling and trafficking, and other areas where the program plays an important role. While it was difficult for the evaluation to fully assess program effectiveness, stakeholder perceptions and limited data suggest that the program makes an important contribution to agency operations.

The extent to which the program's intelligence products adequately inform key decision makers of threats and trends and support intelligence-based decisions could not be fully determined. However, stakeholders expressed general satisfaction with intelligence products, such as strategic threat profiles, target profiles, lookouts and bulletins.

The evaluation draws on examples of intelligence-led seizures and stakeholder perceptions to illustrate the value of the program to disrupting criminal activity. According to the Integrated Customs Enforcement System (ICES) data, the value of intelligence-led commercial seizures was consistently higher than that of border service officer (BSO)-led seizures, which is indicative of intelligence and intelligence products making a positive contribution in the commercial stream to keeping inadmissible goods from entering Canada. Data limitations prevented an assessment of other important contributions the program makes to areas such as fraudulent immigration, human smuggling and trafficking.

Program management felt that the FB-04 classification of the intelligence analyst (IA) position poses challenges in terms of attracting candidates with the right skills, and would like to increase recruitment from other groups and classifications in order to yield applicants with the specialized skill sets and knowledge required for the IA position. In addition, there were challenges with IAs and intelligence officers (IOs) accessing the training they need, although the impact on program operations is unknown. There are low training completion rates for some core intelligence courses. The program relies on external providers for core training, and there were perpetual challenges with trying to obtain seats on intelligence training courses offered by the Canadian Police College (CPC) and the Privy Council Office (PCO). The Human Resources Branch (HRB) is undertaking efforts to offset some training gaps; however, it is not clear if these plans will sufficiently fill the gap. Lack of training could pose risks to the agency, and therefore a recommendation was made by the evaluation team to improve training access and delivery.

In terms of governance, the evaluation found that oversight by the functional authority and communication and collaboration between headquarters (HQ) and regions needs improvement. Under the Functional Management Model (FMM), new governance bodies were introduced to ensure effective horizontal communication and coordination, but have yet to be used effectively to hold meaningful conversations on program performance and accountability. Although the FMM is supposed to lead to "managing people and priorities more strategically, for better workload balance and results", an optimum regional resource allocation model also has yet to be established.Footnote 1 A recommendation was made for the program to develop and implement a PMF, and to use it as a tool for increasing horizontal reporting and accountability from program stakeholders under the FMM.

According to external partners, the program's activities and outputs make a positive contribution to their ability to achieve their mandates. The CBSA's participation in Joint Force Operations (JFOs) appears to be beneficial, and is seen by internal and external stakeholders as valuable for strengthening partnerships and cultivating relationships that allow for information-sharing between intelligence partners. Both the program and external partners have expressed a desire for the CBSA to able to proactively disclose immigration-related information, including known criminal activity, which it cannot do currently due to the Privacy Act. While the legislated restriction to immigration information-sharing is outside the control of the agency, a review of the Privacy Act is currently underway by the Department of Justice which could result in allowing the proactive disclosure of immigration-related criminal information.

Efficiency

The lack of usable performance data resulted in the inability to fully assess the extent to which the program is administered efficiently. Nevertheless, available data suggests that resources are generally aligned to traveller and commercial volumes, and with the use of proxy measures, the evaluation also found some evidence of return on investment. From 2016 to 2017 to 2020 to 2021, the agency's investment in the program yielded a return ranging from 240 to 430% based on only the top 10 intelligence-led seizures per year, and 390-750% based on all intelligence-led seizure values.

Finally, there is a perception that the program lacks the technological capacity needed for efficient and effective operations. Many regional employees indicated they do not have access to basic tools to conduct analyses and investigations or to the agency's secure network. Systems were felt to be outdated and data analytics capabilities lacking. The evaluation did not independently perform a review of IT systems and tools; however, the program has documented an assessment of data needs versus existing tools which showed that system gaps exist. Given the agency's modernization priority to leverage technology to optimize the power of data analytics, the program is encouraged to develop an information technology roadmap with a view to improving data reliability, storage, access, extraction and analytical capabilities within the program.

Recommendations

The recommendations, as indicated above, are as follows:

- Recommendation 1

- The Vice President (VP) of HRB, in consultation with the VP of the Intelligence and Enforcement Branch (I&E), should develop a roadmap to further advance the development and delivery of core training to intelligence analysts and officers so as to improve access and ensure training needs are met.

- Recommendation 2

- The VP of I&E should update and implement its Performance Measurement Framework, and use it as a tool for increasing horizontal reporting and accountability from Intelligence Program stakeholders (including the regions) under the CBSA's new Functional Management Model.

- Recommendation 3

- The VP of I&E should articulate the data/IT business requirements for the Intelligence Program and engage with the Chief Data Office and the Information, Science and Technology Branch (ISTB) to conduct an options analysis to determine appropriate technology solutions.

Introduction

Evaluation purpose and scope

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the Canada Border Services Agency's (CBSA or "the agency") Intelligence Collection and Analysis Program ("the program"). In accordance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results, the main objective of the evaluation was to examine the relevance and performance (effectiveness and efficiency) of the program for the five-year period of 2016 to 2017 to 2020 to 2021.

The scope of the evaluation was approved by the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee (PMEC) on , as part of the CBSA's 2021 Risk-Based Audit and Evaluation Plan. The following section outlines areas that were in and out of scope for this evaluation. The National Targeting Centre's (NTC) processes were not evaluated because targeting has been identified for an upcoming standalone evaluation. While the NTC processes were scoped out, the evaluation acknowledges that the outputs of the NTC are central to the intelligence function of the agency and its contributions cannot be easily separated from the results achieved by the program.

Scope of the evaluation of the program

In scope:

- Intelligence-related activities completed over the last five fiscal years (2016 to 2017 to 2020 to 2021), and whether they fall within the CBSA's mandate

- Achievement of outcomes related to the program

- Assessment of process efficiency and utilization of resources

- Assessment of specific measurement and reporting challenges of the program

- GBA+ analysisFootnote 2

Out of scope:

- Assessment of the performance and efficiency of partners and decision-makers external to the agency

- The quality of analysis underpinning CBSA intelligence products

- The specific performance/functioning of targeting activities and the NTC

- Assessment of the job performance and/or quality of the products produced by the Confidential Human Source (CHS) Program or other intelligence collectors (e.g., the International Liaison Officer (ILO) network)

- Assessment of the specific roles and responsibilities (job descriptions) of operational staffing positions (intelligence officers (IOs), intelligence analysts (IAs), intelligence desk managers), as this work is already being pursued by the program via an independent consultant

According to the Treasury Board's 2016 Policy on Results ("the policy"), evaluations are to consider using relevance, effectiveness and efficiency as primary issues. The policy also provides departments and agencies the flexibility to focus evaluation scope on program areas of highest priority. The evaluation team developed evaluation questions that focused on the following:

- Program's ability to align its risk and threat priorities with the priorities of the Government of Canada and the CBSA

- Program's ability to inform key decision makers of threats and trends, and support intelligence-based decisions

- Program's ability to lead or contribute to the disruption and/or mitigation of border-related threats

- Effectiveness of the existing tools and systems in supporting the operation of the program

- Extent to which program processes are efficient and resources are used optimally

Program description

The program is represented in the CBSA's Program Inventory within the Departmental Results Framework under the "Border management" core responsibility area. The program supports the Government of Canada's commitment to provide greater security and prosperity for Canadians. The CBSA accomplishes this by facilitating legitimate travel and trade across the border while identifying and mitigating safety and security threats. The program governs the intelligence function across the agency and develops tools for frontline officers to assist in identifying people, goods, shipments and conveyances that may be inadmissible or pose a risk to the safety and security of Canada. The program collects information and develops intelligence products via multiple channels, including: border services officers (BSOs); CBSA's ILOs, who collect information abroad that can then be distilled into intelligence products; Joint Force Operations (JFOs) to which CBSA is a party; surveillance and CHS; agency and partner databases; open sources; and information-sharing with other government departments and law enforcement agencies (LEAs). The program leads the national collection of intelligence and analysis production on:

- contraband issues, such as drug trafficking, firearms smuggling, trade-based money laundering (TBML)

- internal conspiracy and national security issues, such as immigration fraud, human smuggling, human trafficking and serious inadmissibility on grounds of national security or war crimes/human rights violation

The products created by the program fall into one of three general categories:

- Tactical intelligence products, which are developed to plan and prepare for specific, ongoing operations (e.g., alerts, timelines and lookouts)

- Operational intelligence products, which are devised to plan and prepare for future operations (e.g., operational plans, intelligence advisories and briefs)

- Strategic intelligence products, which are designed to help develop and implement overall program strategy or policy and for longer-term strategic planning (e.g., strategic intelligence assessments)

These outputs, as well as the intelligence partnerships in which the agency engages, are intended to drive immediate, intermediate, and ultimate program outcomes as per the program's logic model.

Logic model

At the time of the evaluation, the program was undertaking a review of its key performance indicators (KPIs) as part of an exercise to update its Performance Information Profile and did not have a Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) in place. A logic model for the program is included in Appendix B and identifies the following expected outcomes:

- Immediate outcome

- Timely, relevant and actionable intelligence production to identify threats and heighten situational awareness

- Intermediate outcomes

-

- Tactical and operational decision makers make informed enforcement-related decisions

- Strategic decision makers make informed planning, prioritization and management decisions, with a focus to the allocation of agency resources and efforts dedicated to the highest risks and threats to Canada and Canadians

- Ultimate outcome

- Intelligence contributes to the identification, mitigation and neutralization of risks and threats to the safety, security and prosperity of Canadians and Canada

Program management structures and key stakeholders

Under the CBSA's new Functional Management Model (FMM), the Intelligence and Investigations Directorate (IID) within the Intelligence and Enforcement Branch (I&E) is accountable for the delivery of the program and acts as the functional authority, playing a role in strategic intelligence for the agency. Meanwhile, the CBSA's Regional Intelligence Units interpret direction provided by IID to actively collect, analyze, and produce intelligence products according to regional context.

The IID is divided into four divisions: Intelligence Collection, Analysis and Production (ICAP); Intelligence Targeting Policy and Support (ITPS); Criminal Investigations; and the NTC. The evaluation focused on the first two divisions (as described below), as the latter two were recently, or will soon be, explored via other audits and evaluations and were out-of-scope of this project.

Intelligence Collection, Analysis and Production (ICAP) Division

The ICAP's role is to form a national picture of various threats based on intelligence gathered and reported by the regions and by IAs at HQ, and to disseminate this information. Additionally, ICAP forecasts future threats to inform decision-makers, both at the operational level (e.g., how will an ongoing threat such as increased firearms smuggling evolve over the next six months?) and at the strategic level (e.g., based on the available intelligence, what immigration fraud threats are likely to emerge over the next three years?).

Intelligence Targeting Policy and Support (ITPS) Division

The ITPS is responsible for overall program management, including setting policy and providing oversight, as well as reporting on results as required. The division consists of five units:

- Program Management

- Compliance and Oversight

- Partnerships

- Operational Support

- National Document Centre (NDC)Footnote 3

Importantly, within the Operational Support Unit, the Intelligence and Targeting Operational Centre manages requests for information and disseminates intelligence products, and can therefore be viewed as the program's information-sharing hub.

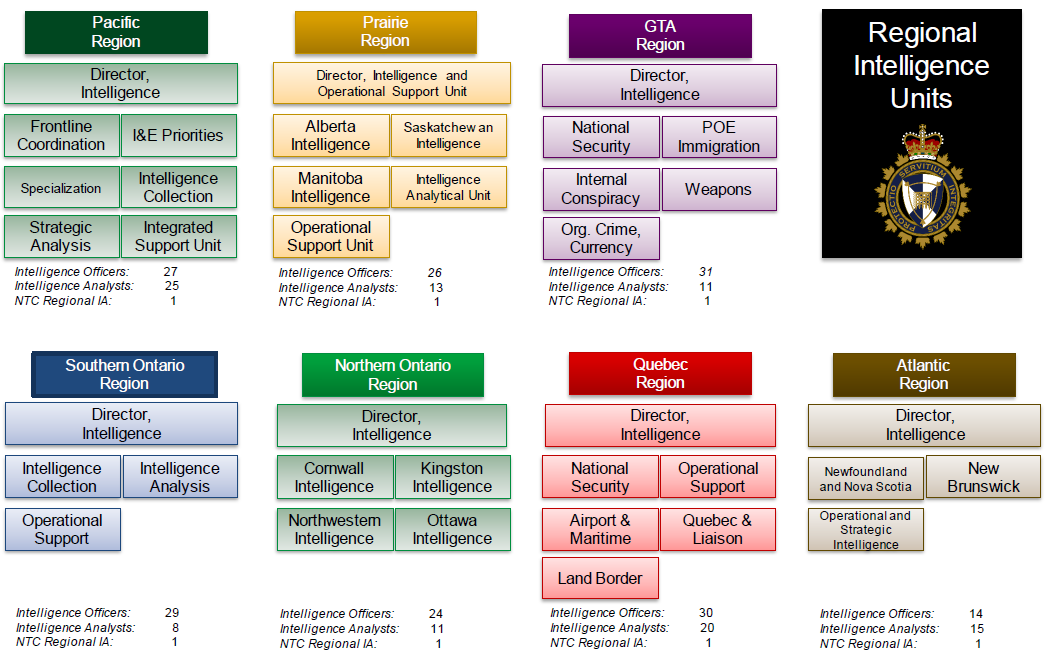

CBSA regions

Each CBSA region has a dedicated Regional Intelligence Unit headed by a Director of Intelligence and Enforcement. The subunits differ from region to region (see Figure 1Footnote 4). A-base funding is allocated by each respective region while B-base project funding is allocated by HQ. Resource allocation does not follow a uniform approach and each region sets its own resourcing levels.

Figure 1: Text version

Figure 1: Regional intelligence units

Pacific Region:

- Director, Intelligence

- Frontline Coordination

- I&E Priorities

- Specialization

- Intelligence Collection

- Strategic Analysis

- Integrated Support Unit

Number of employees:

- 27 intelligence officers

- 25 intelligence analysts

- 1 NTC regional IA

Prairie Region:

- Director, Intelligence and Operational Support Unit

- Alberta Intelligence

- Saskatchewan Intelligence

- Manitoba Intelligence

- Intelligence Analytical Unit

- Operational Support Unit

Number of employees:

- 26 intelligence officers

- 13 intelligence analysts

- 1 NTC regional IA

GTA Region:

- Director, Intelligence

- National Security

- POE Immigration

- Internal Conspiracy

- Weapons

- Org. Crime, Currency

Number of employees:

- 31 intelligence officers

- 11 intelligence analysts

- 1 NTC Regional IA

Southern Ontario Region:

- Director, Intelligence

- Intelligence Collection

- Intelligence Analysis

- Operational Support

Number of employees:

- 29 intelligence officers

- 8 intelligence analysts

- 1 NTC regional IA

Northern Ontario Region:

- Director, Intelligence

- Cornwall Intelligence

- Kingston Intelligence

- Northwestern Intelligence

- Ottawa Intelligence

Number of employees:

- 24 intelligence officers

- 11 intelligence analysts

- 1 NTC regional IA

Quebec Region:

- Director, Intelligence

- National Security

- Operational Support

- Airport and Maritime

- Quebec and Liaison

- Land Border

Number of employees:

- 30 intelligence officers

- 20 intelligence analysts

- 1 NTC regional IA

Atlantic Region:

- Director, Intelligence

- Newfoundland and Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick

- Operational and Strategic Intelligence

Number of employees:

- 14 intelligence officers

- 15 intelligence analysts

- 1 NTC regional IA

Other key stakeholders and clients

The program works closely with partners within and outside of the agency, both as clients (those who use the intelligence produced) and sources of intelligence. Internally, the program serves anyone from BSOs at the frontline to senior officials and policy-makers in different business lines throughout the agency. The program works with CBSA ILOs and CHSs. Externally, intelligence staff work in JFOs with other LEAs, including provincial and municipal police services. They work closely with other government departments and agencies such as Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), the Department of National Defence (DND) and the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), among others. International partners include B5 and M5 partners (Australia, New Zealand, the United States and the United Kingdom).

Program expenditures

Program expenditures remained relatively stable over the review period (Figure 2). CBSA's Corporate Administrative System (CAS) figures included expenditures for the eManifest projectFootnote 5 as well as those of the International Program. After removing those amounts, a refinement of expenditures shows the program spent between $41 million and $53.3 million (including salary, operations and maintenance, and capital expenditures of HQ and regions) between 2016 to 2017 and 2020 to 2021.Footnote 6

| Fiscal year | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS program expenditures | 70.5 | 65.1 | 79.9 | 74.3 | 82.9 |

| Refined program expenditures | 43.4 | 41.8 | 53.3 | 45.3 | 52.1 |

Evaluation methodology

Data collection and analysis for this evaluation were conducted between June and ; both qualitative and quantitative research methods were used. The evaluation team conducted interviews with program officials at all levels in HQ and the regions and with key stakeholders within the agency; reviewed key documentation; performed benchmarking of performance measurement approaches of intelligence activities through a review of national and international literature; reviewed operational, performance, human resources and financial data; and sought the views of external law enforcement partners (domestic and international) through questionnaires. Two separate surveys of intelligence users were planned (one of frontline personnel and one of senior program management); however, due to resourcing and time constraints, these surveys were not conducted, thus restricting the GBA+ analysis planned for this evaluation.

Performance measurement and data limitations for the program were significant and, in many areas, undermined the evaluation's ability to determine the performance and contributions of the program. This will be discussed further in section Performance measurement and data limitations.

Evaluation findings – relevance (alignment and priorities)

Finding 1: Program activities were relevant to agency operations and conducted within the CBSA's legislative parameters and mandate.

The Canada Border Services Agency Act (2005) provides the CBSA with legislative authority to deliver integrated border services that support national security and public safety priorities and facilitate the free flow of persons and goods. The main statutes that facilitate the CBSA's work are the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2001) and the Customs Act (1985).

The CBSA's legislative authority for intelligence collection is derived from subsection 31(2) of the Interpretation Act (1985), which states that "where power is given to a person, officer or functionary to do or enforce the doing of any act or thing, all such powers as are necessary to enable the person, officer or functionary to do or enforce the doing of the act or thing are deemed to be also given."Footnote 7 Pursuant to subsection 32(2) of the Interpretation Act, the program is part of the program delivery chain that supports the CBSA's enforcement mandate. To this end, CBSA intelligence activities support the prosecution of offences under the Customs Act and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act with respect to identifying and interdicting people and goods that are not authorized to enter or remain in Canada.

The CBSA derives lawful authority from its statutory law enforcement mandate to conduct both covert surveillance and operations involving CHSs, particularly where the use of such techniques is related to the administration and enforcement of the Customs Act and Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, and not for some other unrelated purpose. When legislative authority is not granted to the agency to investigate certain areas (e.g., terrorism or organized crime) the CBSA can assist other authorized law enforcement agencies by providing intelligence support where a border nexus exists.

Finding 2: While program activities are aligned with Government of Canada and CBSA priorities, there is an opportunity to explore better alignment of intelligence activities to other business line priorities.

The program supports the Government of Canada's priority to protect the safety and security of Canadians both at home and abroad. Based on a review of priorities and interviews with key stakeholders, there is general consensus that intelligence activities are in line with both Government of Canada and CBSA priorities. The evaluation reviewed ministerial news releases and announcements on issues pertaining to border intelligence and found that while new areas of subject matter often emerge, these new areas still fall into existing program priorities. Stakeholders suggested that this continued alignment with ministerial direction makes it easier to adapt to emerging issues.

Concerns were raised regarding the lack of alignment of program priorities with those of other CBSA programs/divisions (namely the Criminal Investigations Division, Travellers Branch and Commercial and Trade Branch). Interviewees suggested that this has hindered the program's ability to provide assistance to other parts of the agency as resources are assigned based on priorities, leaving no room to work on non-priority issues. These concerns were echoed by stakeholders who expressed a need for the program to play a larger role in areas beyond immigration and customs (such as commercial and trade).

Finally, the regions also expressed some challenges with aligning their own emerging priorities to national intelligence priorities, which had an impact on regions' ability to assign resources. For example, automobile theft and exportation was a priority in two regions. While the first region was unable to align the issue with a national priority and thereby assign resources to it, the second was able to make a link to the TBML priority and thus devote resources to it. HQ interviewees suggested that priorities set by the functional authority are meant to be broad enough to allow the regions flexibility to implement actions based on regional needs, but regions sometimes misinterpret HQ priorities. This could be indicative of miscommunicated priorities rather than a lack of alignment per se.

[redacted]

The challenge in reconciling intelligence priorities within the agency could be linked to the new FMM (which is in the early stages of steady state), with program areas continuing to adapt to the new structure. FMM challenges, along with an associated recommendation, are further explored in section FMM and the Intelligence Program.

Finding 3: The CBSA intelligence branch and its external partners perform complementary work while respecting the limits of their own mandates.

Under the Public Safety Canada portfolio, the CBSA is required to work with its intelligence partners in a cohesive and integrated way to promote Canada's security. Stakeholders confirmed that the CBSA Intelligence Program and its LEA partners, both domestic and international, perform complementary and integrated intelligence work. While there is a certain degree of overlap that exists, internal and external program stakeholders agreed that the CBSA conducts intelligence activities that are unique to its own mandate. The one exception observed by the evaluation is the recent work of the RCMP at ports of entry, as outlined in the draft RCMP 'Border Integrity Program' (a strategy developed to increase RCMP domain awareness in "the land, air, and maritime domains of Canada's borders, specifically between the ports of entry, at the ports of entry and across the Arctic"). While the RCMP has jurisdiction for criminal activity taking place between ports of entry, the CBSA is responsible for anything occurring at the port of entry. This may be an area requiring close collaboration with the RCMP to ensure that no duplication of efforts arise in the future, and could be examined in future evaluations.

Evaluation findings – effectiveness

Performance measurement and data limitations

Finding 4: The program's performance measurement and data challenges prevented meaningful reporting on program outputs and outcomes, and thus effectiveness.

The program has not yet implemented a Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) due to the challenges associated with measuring the outcomes of intelligence activities. At the time of the evaluation, ITPS had collected limited data on program outputs and was in the process of reviewing and developing its performance indicators; baselines have yet to be established.

A benchmarking exercise of domestic and international performance measurement practices in the field of intelligenceFootnote 8 indicated that the program faces performance measurement challenges similar to those of other intelligence organizations, including:

- attribution (measuring direct impactFootnote 9 and the intangible nature of preventionFootnote 10)

- It is difficult to determine the exact impact that intelligence outputs have on results, such as the number of seizures made or the number of illicit incidents that were prevented. The program focuses much of its work on the prevention and disruption of criminal activity, both of which are difficult to measure and to accurately attribute.

- dataFootnote 11

- Collecting data that directly links to outcomes is inherently a challenge for intelligence organizations. Due to the nature of intelligence activities, it is sometimes difficult for staff working the strategic and planning side of an organization to examine any area involving operationally sensitive data that was collected on a "need-to-know" basis. Data that is unreliable or incomplete for varying reasons (e.g., data input errors or absence of an adequate system to collect the data) presents further challenges to the program's ability to measure outcomes.

- type of measures usedFootnote 12

- In the absence of relevant measures, process-based measures can be used to assess effectiveness of program delivery; however, these will only link the process to outputs rather than to the program outcomes (e.g., mitigation and neutralization of risks and threats), limiting the ability to assess the extent to which the program is contributing to its expected results.

In addition to the performance measurement challenges outlined above, the evaluation also experienced numerous data issues which prevented an assessment of program effectiveness. When data was available, it was often incomplete, under-reported or misreported – a challenge that affects the program but is not necessarily within the control of the program, as multiple stakeholders across the agency are responsible for data entry into the various CBSA systems.

Due to data limitations, the evaluation was not able to determine the effectiveness of the program at addressing internal conspiracies and national security issues or combatting contraband issues (notably firearms and TBML). It was not possible to determine the effectiveness of the program at preventing human trafficking and human smuggling due to a lack of data and challenges in determining the contribution of intelligence when data is available.Footnote 13

Similarly, on the international front, it was not possible to quantify the program's contributions to agency efforts to "push the border out" from working with partners to both intercept illicit contraband or inadmissible persons prior to their arrival at POEs, as well as assisting partners in intercepting similar threats arriving at their borders from Canada. Future performance measurement needs to be reflective of, and effectively track, the wide range of intelligence work undertaken by the program.

The evaluation relied mostly on an analysis of drug seizure data to provide anecdotal examples of program contributions, but even then experienced challenges. The reliability of Integrated Customs Enforcement System (ICES) seizure data was poor and determining intelligence-led seizures in ICES required numerous assumptions. The way in which data is inputted by BSOs into ICES varies and the necessary oversight does not always exist to ensure consistency in data entry. This makes it challenging when trying to identify the potential intelligence-related impact. For example, the three largest valued seizures taken from ICES for the evaluation reporting period were entered as being worth billions of dollars instead of in the range of hundreds or thousands of dollars. Data entry issues could potentially be caused by keying errors or varying assumptions of what constitutes "value".

Three examples provided in the table that follows highlight the challenge of reporting on the value of intelligence-led seizures. In 2018 to 2019, a major seizure of 1,500 kg of an MDMA (ecstasy) precursor was entered as $140 million, which represents the value of the potential MDMA that could be produced using that precursor chemical (and not the actual value of the precursor substance). In comparison, in , an intelligence-led seizure saw 1,500 kg of a fentanyl precursor seized. This seizure prevented the production of over 2 billion doses of fentanyl with an estimated street value of up to $40 billion. However, in ICES, this seizure was assessed at $3 million. These examples illustrate the difficulty in having the dollar value of intelligence-led seizures accurately recorded in CBSA systems.Footnote 14 It is also important to note that there is a non-financial (socio-economic) cost avoidance from seizures that is not captured in agency reporting, including cost-avoidance related to crime, healthcare and justice.

| Year | Intelligence-led seizure | Financial value | Non-financial value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 to 2019 | 4,000 kg PMK (MDA (ecstasy precursor) | Prevents the production of 25 million doses of MDMA (ecstasy) valued at $140 million | At minimum, a reduction in illicit toxicity deaths, strains on the healthcare system and criminal justice systems and potential to export outside of Canada |

| 2020 to 2021 | 1,000 kg opium | $10 million | |

| 2020 to 2021 | 1,500 kg 4-Piperidone (fentanyl precursor) | Prevents the production of over 2 billion doses of fentanyl valued at $40 billion | |

| Source: ICES, | |||

In addition, BSOs are required to identify the cause for a resultant referral in ICES through a drop-down menu, thereby asking the BSO to attribute the seizure to either themselves, intelligence or other drivers (targeting, detector dog, etc.). The fact that only one option can be selected from the drop-down menu likely contributes to the underreporting of intelligence-led seizures in ICES, as intelligence products eventually make their way into a BSO's training and intuition, so the distinction between what was intelligence-influenced (and what was not) becomes less clear over time. A review of the referral and sub-referral types available in ICES to allow multiple attribution options to be selected by BSOs could increase the accuracy of intelligence-led reporting (e.g., allowing a BSO to attribute the resultant to themselves as the first selection and to an intelligence brief as the second selection from the drop-down menu). In addition, a clear definition and methodology in the program's PMF as to how ICES seizures are attributed to intelligence would be beneficial.

The challenges with performance measurement and data limitations have prevented the program from knowing if it is delivering on the results expected. At the time of the evaluation, a review of the program's KPIs was underway that included the establishment of baseline indicators for performance metrics and future performance reporting. Alternate performance reporting strategies can be found in Appendix C.

Intelligence-based decisions

Finding 5: The extent to which the program's intelligence products adequately inform key decision makers of threats and trends, and support intelligence-based decisions could not be fully determined; however, stakeholders expressed general satisfaction with intelligence products.

The data limitations described in section Performance measurement and data limitations restricted the evaluation's complete assessment of the value-added of intelligence products to agency decision makers. Regardless, interviews with senior agency officials in different program areas pointed to a general satisfaction with intelligence products received, even when program contributions to other areas of the agency were not always clear. It was also difficult to assess the extent to which the intelligence products were timely and relevant, although program staff (HQ and regional managers) indicated that the limited feedback they received was always positive. The program recently launched a survey tool to receive prompt feedback on ICAP products from the different program areas it serves, which is a first step in informing future assessments of the value of intelligence products. Additionally, there is an opportunity for the program to use future iterations of this survey to seek additional feedback on how to further address client needs.

Another issue raised in the course of this evaluation was the extent to which intelligence products are being actioned, both tactically at the front line, or more strategically in influencing agency decisions in program and policy areas. Given the program's challenges with performance measurement and attribution, the evaluation was unable to provide an assessment in this regard. The program has, however, identified this as an area of concern and is developing an "Intel-to-Action" initiative which is expected to strengthen the use of certain intelligence products originating from the ICAP unit in HQ by following up with internal and external stakeholders on actions taken as a result of those intelligence products. This initiative remains in the planning phase and has not yet been rolled out.

Disrupting border-related threats

Finding 6: While stakeholders felt that the program disrupts criminal activity, the extent of program contributions was difficult to assess.

While there was general consensus from various stakeholders that program activities lead to the disruption of criminal activities, there is currently no way to measure the extent to which this takes place nor its impact. Nonetheless, there are examples of intelligence-led seizures (i.e., seizures in ICES attributed to intelligence products) that have prevented a high value of inadmissible goods from entering Canada.Footnote 15 Figure 3 below illustrates the 10 highest valued ICES seizures annually from 2016 to 2017 to 2020 to 2021 and their source (BSO-, targeting- or intelligence-led). Based on this data, the majority (60%) of the highest value seizures for the agency in this period were intelligence-led.

| Intelligence | Target | BSO | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 14 | 18 | 8 |

Source: ICES,

Another example of program contributions to disrupting criminal activity can be found in Figure 4 below, which illustrates the trend in intelligence-led seizures in the commercial stream relative to BSO-led seizures. While intelligence-led seizure volumes reflect a trend similar to BSO-led seizure volumes over time, the value of intelligence-led commercial seizures is consistently higher. This is indicative of intelligence and intelligence products making a positive contribution within the commercial stream to keeping inadmissible goods from entering Canada.

| Year | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligence seizure value (Value $100,000) | 92 | 1,121 | 2,043 | 556 | 845 |

| BSO seizure value (Value $100,000) | 95 | 163 | 153 | 353 | 146 |

| Intelligence volume of seizures | 160 | 64 | 107 | 351 | 73 |

| BSO volume of seizures | 282 | 262 | 449 | 519 | 251 |

Source : ICES, accessed

Finally, Figure 5 and Figure 6 below present evidence of positive program contributions in terms of specific drug seizures. Analysis of intelligence vs. BSO-led seizures for cocaine and heroin indicated that, in general, the program contributes to a higher value of drug seizures through intelligence-led actions compared to BSO-led enforcement alone. While the number of intelligence-led seizures is much smaller, the value of intelligence seizures is comparable or in some years significantly greater than the value of BSO-led seizures.

| Year | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligence cocaine seizures value (Value $100,000) | 1,594 | 2,480 | 942 | 668 | 756 |

| BSO cocaine seizures value (Value $100,000) | 665 | 776 | 857 | 482 | 402 |

| Intelligence cocaine seizures volume | 235 | 245 | 106 | 98 | 79 |

| BSO cocaine seizures volume | 382 | 439 | 556 | 426 | 319 |

Source : ICES, accessed

| Year | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligence heroin seizures value (Value $100,000) | 252 | 250 | 341 | 229 | 0 |

| BSO heroin seizures value (Value $100,000) | 179 | 238 | 153 | 240 | 222 |

| Intelligence heroin seizures volume | 29 | 21 | 25 | 15 | 0 |

| BSO heroin seizures volume | 183 | 194 | 146 | 121 | 197 |

Source : ICES, accessed

A regional breakdown of the number and value of intelligence-led seizures by drug type is suggestive of a pattern of importation of illicit goods across the country, which is heavily influenced by traveller and commercial traffic patterns and large urban population centres that offer markets for illicit goods. Figures 7 and 8Footnote 16 illustrate the program's contributions by region for cocaine and fentanyl seizures respectively, displaying the variances in intelligence-led seizures across regions. Greater Toronto Area (GTA), Southern Ontario Region (SOR) and Quebec had the highest values of cocaine seizures, while fentanyl seizures, were mostly concentrated in Pacific and GTA, with a small amount in Quebec.

| Regions | ATL | NOR | QUE | GTA | SOR | PRA | PAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine seizure value (in $ millions) | 55 | 15 | 175 | 206 | 118 | 54 | 20 |

| Volume of seizures | 28 | 9 | 80 | 291 | 84 | 202 | 69 |

Source : ICES, accessed

| Regions | ATL | NOR | QUE | GTA | SOR | PRA | PAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value of fentanyl seizures (Value $10,000) | 0 | 0 | 5.0 | 63.2 | 0 | 0 | 327.6 |

| Volume of seizures | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 18 |

Source : ICES, accessed

[redacted]

Recruitment, classification and training

Finding 7: The FB-04 classification of the IA position poses challenges in terms of attracting candidates with the right skills.

Within the program, both IAs (non-uniformed) and IOs (uniformed) are classified at the FB-04 group and level. While this classification may be appropriate for IOs given the operational nature of the position, management questioned whether the classification of IAs as FBs is aligned with the expectations of the role, given that the IA role is less operational and more analytical in nature.

Currently, the primary group from which the agency recruits IAs is from the BSO (FB-03) pool. While non-FB employees can apply to the FB-04 IA position, interviewees suggested that the majority of applicants come from the BSO pool. While vacancy rates do not point to concerns with the ability to fill positions, program management indicated that the FB-03 pool may not necessarily comprise a diverse group of individuals with the right skills and experience for the IA position. Interviewees felt that while the BSOs bring front line operational experience, the candidates applying do not always have the required analytical skills. External recruitment would also provide an opportunity to bring a greater diversity of perspectives, ideas, skills, disciplines, and experience to the IA workforce.

[redacted]

In addition, recruitment from the BSO pool has historically had known negative downstream impacts on the availability of regional resources, for which HRB is currently seeking a solution. A force generation review is currently being undertaken by HRB. The initial phase of this review will focus on ensuring sufficient capacity of BSOs for the regions and will eventually assess the downstream impacts of drawing on the FB-03s to fill FB-04 positions. A classification review initiative is also underway by HRB, which will eventually review all FB positions in the agency to determine the appropriateness of the FB classification.

Program management expressed an interest in increasing recruitment from other groups and classifications to better align the applicants with the specialized skill sets and knowledge sought in the IA position. For example, employees in the Economics and Social Science Services (EC) group (within and outside the CBSA) may have the desired analytical-based skill sets and could potentially be recruited to fill existing IA vacancies; however, the FB classification is not necessarily attractive to employees in the EC group.

To explore the challenges with recruiting from outside the FB-03 group, the evaluation compared the CBSA's IA classification and career progression to that of similar organizations with IAs. Other federal intelligence partners (such as the RCMP and DND) also have IAs in civilian and non-uniformed positions, but classify them as ECs, with levels ranging from junior to senior (EC-04 to EC-06, respectively). Such an approach provides for career progression, allowing IAs to progress from junior to more senior positions. In contrast, all IAs in the CBSA are at the FB-04 level. In addition, CBSA IAs are paid a maximum of $93,000Footnote 17 annually due to only having one group and level, compared to $116,000 annually (maximum) for experienced RCMP/DND IAs at the EC-06 level. It is therefore apparent why those in existing EC positions may be less likely to apply to the CBSA IA position.

A recent report on culture in the I&E Branch identified IAs as one of the few FB groups in the agency to be overrepresented by women (women occupy 68% of IAs positions, compared to 34% of other FB positions in the agency).Footnote 18 Applying the gender lens lends itself to a GBA+ observation whereby lower comparative pay rates and obstacles to career progression for the IA position primarily affect women.

Summary of challenges recruiting externally for the intelligence analyst position (FB-04)

- Limited recruitment

- Reliance on FB-03 pool does not give consideration to other groups with analytical skills

- Difficulty attracting other groups (e.g., ECs) to FB positions

- Fewer benefits

One level = no career progression

- Less pay

CBSA IA (FB-04) salary caps at $93,000, RCMP/DND senior IAs (EC-06) salary caps at $116,000

Aside from recruitment challenges, concerns surrounding the retention of IAs were raised by interviewees. Current IAs have expressed frustration with the financial implications of the recent changes to the FB Collective Agreement (). Under the new FB Collective Agreement, IOs (uniformed) are eligible for shift differentials, regular overtime, and are granted a $5,000 annual meal allowanceFootnote 19 which is not offered to IAs (non-uniformed). Additionally, as non-uniformed positions, IAs are not armed while both IOs and intelligence managers are, resulting in a potential roadblock for IAs wishing to progress to an intelligence manager position.Footnote 20 In the opinion of program management, the recent financial disadvantages experienced by IAs compared to their IO colleagues, compounded by the lower pay and fewer opportunities for advancement compared to IAs in other departments/agencies, could further exacerbate the loss of IAs to other similar departments such as the RCMP, CSIS and DND. Data, however, does not indicate any concerns with attrition to OGDs in recent years, with the average OGD attrition rate being 0.6% for IAs during 2016 to 2017 to 2020 to 2021. Footnote 21

Finding 8: Access to training is insufficient to support the intelligence analyst and officer functions.

Training was identified by interviewees as one of the major challenges faced by the program and confirmed by the evaluation through document review and data analysis. Gaps were documented in the 2021 to 2022 I&E integrated business plan and again in the upcoming fiscal year plan, indicating that training challenges persist. While insufficient data exists to measure the overall impacts of training gaps on program operations, program management stated that new recruits often work for seven or more months without formal intelligence training. This has contributed to newer staff at both operational and management levels not having a clear understanding of intelligence work and their roles and responsibilities therein.Footnote 22 Furthermore, there is a perception that training is one factor impacting collaboration and communication between IAs and IOs, as there is a perceived misunderstanding of each other's roles within the intelligence collection and analysis process. Interviewees believe this could initially be addressed during training and then further socialized through other mechanisms.

The main challenge appears to be training availability. While the National Training Standard (NTS) lists all mandatory, core and function-specific training for IOs and IAs that is required to perform their current roles, interviewees stated that staff often encounter challenges with finding available training seats. This is because some core training historically has only been available through external providers, such as the Privy Council Office (PCO) and the Canadian Police College (CPC), which provide training to numerous intelligence organizations and law enforcement agencies (including other areas within CBSA) whom all vie for limited seats. For example, the agency does not have a formal partnership with the CPC for their intelligence training, and therefore priority is often given to the policing community. In addition, seats allocated to the CBSA for the PCO 'Entry level course for Intelligence Analysts' must be shared with other program areas such as Security Screening who also rely on the same course offering for their core training.

Difficulties in obtaining seats on training courses offered by CPC and PCO were confirmed by the evaluation through document reviewFootnote 23 and training data analysis, which showed low training completion rates for some core intelligence courses. Table 2 below identifies overall completion rates for the intelligence-specific courses listed under the existing NTS for all current IAs and IOs hired from February 2005 (when the data collection began) to .Footnote 24 It should be noted that courses listed under the current NTS were introduced at various times and some IAs/IOs may have been deemed by management to have sufficient experience in lieu of certain training. That being said, completion of CPC training is only 6% for IAs and 12% for IOs. Less than half of active IAs and IOs have completed the PCO training (a foundational course for IAs and a competency-specific course for IOs), but this is generally in line with the overall rate of completion for internal CBSA training courses for IAs and IOs.Footnote 25

| CBSA Courses | PCO Course | CPC Courses | All NTS Training | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligence analysts | 41% | 32% | 6% | 37% |

| Intelligence officers | 56% | 49% | 12% | 54% |

| Source: CAS, up to | ||||

Not ensuring available training poses a risk to the agency in terms of liability (e.g., officers being called to testify in court) and could cause employee performance issues, as employees are not being set up to succeed in their jobs. HRB has begun exploring alternate training options to offset external training that is difficult to access,Footnote 26 including external training and has indicated tentative plans to develop semi-annual blocks of internal CBSA training for IAs/IOs to ensure that new recruits receive some training in a timely manner after joining. It is unclear if these plans are being developed in collaboration with program staff and/or if they will sufficiently fill the gap.

Some regions indicated that they had developed or contracted their own training to fill gaps, which raises concerns about the standardization of training across the agency as well as the contracting of external (non-CBSA) trainers who may not be sufficiently certified. In addition, the ongoing pandemic has increased challenges for both in-person training and mentorship of new employees, which has been relied upon in place of training according to program staff.

[redacted]

Given the potential risks, a recommendation is being made by the evaluation to explore the development of further training solutions to improve access to training. By providing training internally, HRB could explore options for a complete induction program for new IOs and IAs offered at different times of the year based on recruitment patterns. For example, the CBSA's International Program requires ILO recruits to attend a three-week induction training block before starting their position. The program could benefit from a similarly dedicated program which could offer consistent and complete training for new intelligence personnel. Such a solution for the program would need to consider the current model used by the CBSA where IOs and IAs are recruited and on-boarded individually at different times throughout the year (not as a collective cohort).

Recommendation 1: The VP of HRB, in consultation with the VP of I&E, should develop a roadmap to further advance the development and delivery of core training to intelligence analysts and officers so as to improve access and ensure training needs are met.

FMM and the Intelligence Program

Finding 9: Oversight by the functional authority and communication and collaboration between HQ and regions need improvement.

The CBSA's new FMM has recently been implemented and some aspects of the reorganization are still being ironed out. Looking at the impact of the FMM on the program provides an opportunity to make necessary adjustments, as needed, during the early stages of steady state.

Reporting relationships: HQ and regions

HQ

- President (AOC)

- VP, I&E (AOC, BLMB)

- DG, Intelligence (BLMB)

- Intelligence

Regions

- E/VP (AOC)

- RDG (AOC, BLMB)

- Regional director

- Intelligence

With that in mind, the evaluation identified some challenges that could be negatively impacting communication and oversight for the program. Interviews with key program stakeholders suggested that the regions and HQ are still in some ways working in silos, with isolated reporting relationships, despite the new FMM model's intent to enable HQ and the regions to "work together more effectively."Footnote 27 As the reporting relationships show, the regions report to their respective regional directors general (RDGs) and up to the Executive Vice-President, while the functional authority for the program (DG, IID) reports to the VP.

The FMM introduced a number of governance bodies to ensure effective horizontal communication and coordination, including the Intelligence and Enforcement Business Line Management Board (BLMB) and the Agency Operations Committee (AOC). Footnote 28 The program indicated that they have not maximized the use of these (or other) bodies as a means to promote regional accountability, including performance reporting. Meaningful conversations on program performance and accountability have not been held at BLMB and AOC meetings. Program stakeholders interviewed for the evaluation continue to view collaboration, communication and reporting between HQ and the regions as limited.

At the working level, sentiments varied from region to region. Some regions reported having very positive relationships with HQ and stated that the newly established Intelligence Desk ModelFootnote 29 allowed for monthly calls, check-ins, and increased direction from desk heads at HQ. Other regions reported that they have no communication from HQ and feel that HQ does not have a clear understanding of regional operations and the support required. Personal relationships were often relied upon to maintain lines of communication. Some HQ staff also expressed a lack of clarity/oversight on regional operations, with a desire to improve the relationship moving forward.

Another challenge to the program is the inconsistent allocation of resources across regions due to the absence of a regional resource allocation model. Under the FMM, senior leaders are supposed to "have more accountability over a specific area of responsibility" and an improved "ability to manage people and priorities more strategically, for better workload balance and results."Footnote 30 However, within the program, regional intelligence resources are still allocated by respective RDGs without much accountability reporting to HQ. [redacted]

| Region | ATL | QUE | NOR | GTA | SOR | PRA | PAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligence analyst | 14 | 18 | 7 | 13 | 8 | 13 | 29 |

| Intelligence officer | 14 | 36 | 19 | 29 | 31 | 25 | 29 |

Source : CBSA CAS data

Implementing performance reporting from the regions could allow HQ to better identify the optimal resource allocation model and thus provide more oversight over, and direction to, the regions. It would also improve communication, collaboration and priority setting for the program. In addition, the program could benefit from conducting threat risk assessments by region or mode to determine how best to use resources.

As the FMM remains relatively new in the agency, some of these challenges may be alleviated by encouraging the program's functional authority to establish and communicate expectations for the regions to report on operational performance.

Recommendation 2: The VP of I&E should update and implement its Performance Measurement Framework, and use it as a tool for increasing horizontal reporting and accountability from Intelligence Program stakeholders (including the regions) under the CBSA's new Functional Management Model.

External partnerships

Finding 10: According to external partners, the program's activities and outputs make a positive contribution to achieving their mandates; the CBSA is limited by law in how much information it can share with external partners.

The CBSA actively engages with domestic and international partners, including Border 5 and Migration 5 countries, to exchange intelligence-based information that supports effective delivery of its programs. Information-sharing with partners is done in accordance with a written agreement such as a memorandum of understanding (MOU). In the course of the document review, existing MOUs were found to be up to date and relevant to the program's priorities as they pertained to sharing information with the external organization in support of national safety and transnational criminal activities.

The program's contributions to external partnerships were mostly categorized by interviewees as very effective. The perception from CBSA IOs was that successful partnerships were often based on long-standing relationships that developed over years, as trust-building in the intelligence community was central to opening lines of communication. Questionnaire feedback received from domestic and foreign law enforcement partners on their relationship with the CBSA's program was overwhelmingly positive. The RCMP, FINTRAC, Sûreté du Québec and the United States Department of Homeland Security's Immigration and Customs Enforcement all reported excellent working relationships with the program. They indicated that the intelligence products they received, and the overall relationship with the program, were invaluable.

[redacted]

Finding 11: The CBSA's participation in JFOs appears to be beneficial, and is seen as valuable for strengthening partnerships and cultivating relationships that allow for important information-sharing between intelligence partners.

As an extension of partnerships with LEAs, program staff participate in JFOs in support of the CBSA's mandate and priorities, guided by the principles of cooperation, recognition of respective expertise and the effective, efficient use of Government of Canada resources. Overseen by ITPS, JFOs are ongoing or regularly occurring activities lasting over six months with international or domestic law enforcement partners, designed to reach well-defined objectives that relate to a CBSA Integrated Enforcement and Intelligence Priority.Footnote 31 Through participation in a JFO, CBSA officers may be embedded full-time or part-time within another agency.Footnote 32

[redacted]

Data analysis did not provide conclusive evidence on the value of CBSA participation in JFOs. Figure 10 below illustrates the number of JFOs by region and the resulting CBSA arrests effected, lookouts and targets issued, as well as case files opened for the period of 2017 to 2018 to 2020 to 2021. While it is difficult to determine the value of the CBSA's participation in a JFO based on these factors, the data indicated that the impact of participation varies considerably. [redacted] had the most active JFOs and reported the largest number of arrests and lookouts/targets issued, compared [redacted] which had the lowest participation in JFOs and the fewest resulting impacts. [redacted] had the largest number of lookouts/targets per JFO. [redacted] reported the most open case files, but with relatively fewer arrests and lookouts/targets issued.

| Region | ATL | QUE | NOR | GTA | SOR | PRA | PAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrests effected | 13 | 3 | 123 | 1,449 | 71 | 690 | 56 |

| Lookouts/Targets issued | 714 | 114 | 289 | 1,051 | 307 | 825 | 473 |

| Case files | 109 | 82 | 1,595 | 1,171 | 331 | 966 | 336 |

| JFOs | 19 | 8 | 23 | 48 | 17 | 37 | 17 |

Source: CBSA Joint Force Operations Deck 2021, ICAP

Feedback from external partners on the CBSA's participation in JFOs was very positive and the relationships created through these operations were viewed as important by stakeholders for continued information-sharing. That being said, program managers were more critical of the time and financial investment in JFOs compared to operational staff who saw immense value in the relationships built by JFOs. IOs highlighted that investments in JFOs are required before the value becomes evident. IOs expressed that there are often links to the border that arise months or years into an operation, and without a CBSA presence, the necessary border-related evidence would not be collected by external partners. Several regions felt that the true value of JFOs lies in strengthening partnerships and cultivating relationships that allow for important information to be exchanged.

- Date modified: