Audit of harassment management: Section 1

Introduction

1. Harassment and violence is defined as “any action, conduct or comment, including of a sexual nature, that can reasonably be expected to cause offence, humiliation or other physical or psychological injury or illness to an employee, including any prescribed action, conduct or comment.” When allowed to persist, harassment and violence may have adverse effects on the mental health and engagement of employees as well as the quality of their work.

2. Prevention and resolution of harassment and violence in the workplace is an essential component of effective people management in an organization. Misunderstandings and interpersonal conflicts are inevitable in a complex and demanding work environment that brings together diverse people and where collaboration is essential to success.

3. In , Bill C-65, an Act to amend the Canada Labour Code was enacted by the Government of Canada, to create a more robust approach to addressing harassment and sexual violence in the workplace.

4. The Workplace Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations (the regulations) will help departments better prevent, respond to, and provide support to those affected by harassment and violence in the federal public service.

5. Police, security, and correctional officers are among the occupational groups that tend to be at a higher risk of workplace violence. Footnote 1

6. The regulations require the following activities:

- development of a comprehensive prevention policy

- identification of risk factors that contribute to harassment and violence in the workplace, and developing and implementing preventive measures to mitigate these risks

- development and completion of mandatory harassment and violence prevention training by all employees

- development of a resolution process for employees to report and resolve a workplace harassment and/or violence incident in a timely manner

7. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's (TBS) Directive on the Prevention and Resolution of Workplace Harassment and Violence came into effect . The objective of the directive is to prevent occurrences of workplace harassment and violence by providing healthy, safe and respectful workplace, that is free from all forms of harassment and violence, and to ensure that organizations respond appropriately and without delay to a notice of occurrence of harassment or violence.

8. The new regulation and directive stipulate that the harassment complaint process is “employee driven,” whereby, if the principal party requests an investigation, the agency must investigate.

Significance of the audit

9. The Office of the Auditor General (OAG) conducted an audit of Respect in the Workplace in , and found that the agency's approach to dealing with harassment in the workplace did not do enough to promote and maintain a respectful workplace.

10. The agency's Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) 2020 results highlighted that: Footnote 2

- 16% of employees identified as a victim of harassment in the past 12 months

- approximately 12% of employees did not file a harassment complaint following an incident due to the fact that they “did not know what to do, where to go, or whom to ask”

These results underscored the agency's need to focus on the management of harassment.

11. Since the regulations came into force on , the agency was required to quickly implement processes to adhere to the requirements.

12. CBSA's Code of Conduct sets out the standards for interacting with others, making decisions and working in a professional and values-based environment.

13. The agency created the National Integrity Centre of Expertise (NICE) in to centralize CBSA's management of harassment and workplace violence.

14. Other internal and external stakeholders involved in the management of harassment include: Footnote 3

- Access to Information and Privacy

- Procurement

- Occupational Health and Safety

- Policy Health and Safety Committee Members

- CBSA Management

- Labour Program

- Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer

15. The audit objective is to assess whether the CBSA's key processes to manage harassment and violence promoted a workplace free of harassment and violence in compliance with the TBS Directive, the Canada Labour Code and associated regulations.

16. The scope period for the audit was , to .

17. The audit scope included:

- the design of the agency's harassment and violence complaint process, including the intake of complaints, its triage, analysis, investigations and closure to ensure that the process is clear, coordinated, well-communicated and consistent with the TBS Directive, the Canada Labour Code and associated regulations

- the effectiveness of the agency's prevention measures to foster a workplace free of harassment and violence

18. The audit scope excluded:

- the harassment complaint process, conclusions and recommendations under the former TBS Policy on Harassment Prevention and Resolution Policy (i.e., prior to )

- the effectiveness of the harassment and violence complaint resolution processes

19. Audit methodology:

- Interviewed key stakeholders, held focus groups and consulted other government departments

- Resolution/complaint process walkthrough (4 files)

- Reviewed supporting documents

- Surveyed agency employees

- An Internal Audit Division survey was distributed through the CBSA’s internal daily newsletter from to .

Topics included:

- Communication and prevention

- Training

- Harassment incidents

- Quality of services from NICE

- Other recourse options

Survey response rate:

- Respondents (complete responses): 652

- Headquarter respondents: 36%

- Regional respondents: 64%

- Total agency employees: 16,000

- Response rate: 4%

- Analyzed 652 completed survey responses

Refer to Appendix A for further details on key risks; refer to Appendix B for further details on the lines of enquiry and audit criteria for this Audit Engagement. Refer to Appendix D for further details on the survey.

Statement of conformance

20. This audit engagement conforms to related Treasury Board's Policy and Directive on Internal Audit and the Institute of Internal Auditors' (IIA) International Professional Practices Framework. Sufficient and appropriate evidence was gathered through various procedures to provide an audit level of assurance. The agency's internal audit function is independent and internal auditors performed their work with objectivity as defined by the IIA's International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing.

Audit opinion

21. The agency has developed a harassment and violence policy that is mostly aligned with the TBS Directive and the Canada Labour Code regulations; however, some updates are required to the policy to ensure that all aspects are covered. A workplace assessment was not fully completed; its completion will ensure that the agency is shifting its focus from being reactive (i.e., responding to harassment complaints received) to being proactive in reducing and/or preventing harassment incidents in the workplace. Additional opportunities exist to improve the tracking of training for managers, who play a key role in fostering a harassment free workplace.

22. Overall, the harassment complaint resolution process is well designed; however, challenges in the process that impact the agency's ability to adhere with regulated timeframes should be addressed. These improvements will strengthen the agency's harassment management process and support its efforts in promoting a harassment free workplace.

Key findings

23. The CBSA Workplace Harassment and Violence Prevention (WHVP) Policy has been established in accordance with the regulations. However, some processes related to workplace assessment and preventive measures have not been documented.

24. The agency is addressing the OAG's findings from the Respect in the Workplace audit, by developing and implementing the Respectful Workplace Framework (RWF).

25. A workplace assessment, which is required by the regulations, was not completed. As a result, an inventory and the assessment of the effectiveness of preventive measures was not completed. Available data, such as harassment and grievances numbers, was not yet leveraged to monitor the effectiveness preventive measures.

26. The agency is not monitoring and tracking whether all managers have taken the mandatory harassment training.

27. Although measures were in place to prevent harassment, some survey respondents felt senior management had not done enough to promote a workplace free of harassment including reducing the fear of reprisal when reporting incidents to NICE and other recourse mechanisms in the agency.

28. The resolution process is mostly designed in accordance with the regulations, however the agency has challenges adhering to the regulated timeframes for key stages of the process.

Summary of recommendations

29. The audit makes four recommendations:

- Update the WHVP Policy to fully align with the regulations

- Complete a workplace assessment

- Create new and promote existing preventive tools and measures including reprisal mechanisms, as well as ensure mandatory training for managers is monitored

- Strengthen the resolution process by offering more support to advisors and streamlining the process to meet the timeframes identified in the regulations

Audit findings

The audit resulted in the findings below.

Prevention policy

30. This policy aims to prevent workplace harassment and violence from happening; respond to situations in which harassment or violence have occurred; and, most importantly, support victims of harassment and violence.

31. A comprehensive set of policies, guidelines, and procedures that is aligned with the regulations and applicable directives is essential to direct agency's initiatives to foster a respectful workplace and address workplace harassment and violence incidents.

32. We expected that the CBSA Workplace Harassment and Violence Prevention (WHVP) Policy was developed in alignment with the regulations and directives.

CBSA Workplace harassment and violence prevention policy

33. The CBSA WHVP Policy was jointly developed with Applicable Partners (Customs and Immigration Union, Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada and Canadian Association of Professional Employees).

34. The policy is made available to employees on CBSA's intranet pages (Atlas, Apollo) and was communicated to employees via the CBSA Daily newsletter.

35. Consistent with the regulations, the CBSA WHVP Policy requires the agency to:

- develop a workplace assessment and identify workplace risks

- provide mandatory training

- implement a complaint resolution process

36. The CBSA WHVP Policy, procedures to resolve complaints, and the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, were mostly aligned with the regulations, TBS Directive and other applicable guidance. However, the following areas were not addressed in the policy:

- The regulations require the agency to review and update the workplace assessment every 3 years and/or after a Notice of Occurrence has been received by NICE Footnote 4

- This requirement has not been included or addressed in the CBSA WHVP Policy

- There is a lack of clarity on process details, and the roles and responsibilities for developing and implementing preventive measures to address the workplace risks within 6 monthsFootnote 5

- The agency and the applicable partners (including unions) have not jointly developed or identified a list of qualified individuals who may act as an investigatorFootnote 6

These audit observations are elaborated throughout the report.

37. To ensure that it is well situated to prevent harassment from occurring and help employees who have experienced harassment, the agency should ensure that the CBSA WHVP Policy includes all requirements and related processes from the regulations.

Recommendation 1: The Vice-President (VP) of Human Resources Branch (HRB) in collaboration with applicable partners, should ensure the CBSA Harassment and Violence Prevention Policy is updated to align with the regulations and the TBS Directive, by:

- incorporating process details on the workplace assessment and the implementation of preventive measures

- clearly documenting the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders

- developing and documenting a list of qualified investigators

Management response: Agreed. The VP of HRB will engage the Policy Health and Safety Committee (PHSC) concerning the need to add the above mentioned content to the CBSA Harassment and Violence Prevention Policy and will take action to update the Policy.

Completion date:

Prevention and assessment of harassment

38. Harassment is normally a series of incidents but it can be one severe incident that has a lasting impact on the individual. Source: Canadian Human Rights Commission, What is Harassment.

39. When people work together, conflicts and misunderstandings are inevitable but should not be allowed to escalate to the point of harassment. Workplace harassment, if left unresolved, it can escalate to physical violence. Footnote 7

40. The most effective way to address workplace harassment and violence is to prevent such an occurrence from happening in the first place. Managers play a critical role in setting the tone at the top, by ensuring they:

- foster a harassment and violence free workplace Footnote 8

- promote respectful working relationships amongst their employees

41. 89% of survey respondents (at all levels of management) indicated their role and responsibilities regarding incidents of harassment or violence in their workplace are clear to them.

42. We expected the agency has established and implemented processes to assess its workplaces, identify risks related to harassment and violence, and develop, implement and communicate effective preventive measures to address the risks.

Existing measures to prevent harassment

43. Since the OAG Respect in the Workplace report, Footnote 9 the agency has been working to develop and implement a comprehensive strategy to foster a respectful workplace culture free of incivility and harassment. This strategy, known as Respectful Workplace Framework (RWF), Footnote 10 focusses on enhancing preventive measures, improving response mechanisms and restoring the workplace if harassment and discrimination occurs.

44. Through the development and implementation of the RWF, the agency has dedicated resources to undertake initiatives that may contribute to the prevention of harassment and violence in the workplace. Some of these initiatives completed thus far include:

- character based leadership development training

- the creation of the National Integrity Centre of Expertise Footnote 11

45. The RWF's expected outcome: all CBSA employees, regardless of identity factors, are valued and treated with dignity and respect. CBSA, and Canada, benefit from employees' full inclusion and participation in the workplace.

46. Furthermore, through the framework, the agency is developing strategies to promote diversity and inclusion, implement an Anti-Racism strategy and mental health support strategy, and provide resources and training to prevent workplace harassment and violence.

47. The agency communicates these initiatives and the importance of workplace culture through the CBSA Daily, on Atlas, as well as solicits direct feedback from employees through pulse check/culture surveys. For example, the HRB reminds employees via the CBSA Daily, that they are guided by the agency's shared values of Integrity, Respect, and Professionalism as described in the CBSA Code of Conduct.

48. 496 (77%) survey respondents expressed that there are gaps, which if addressed, could help improve the effectiveness of preventive measures. Areas for improvement suggested by the respondents include effective leadership and soft skill training with focus on early intervention or identification of inappropriate workplace behaviours.

49. 51% of employees disagreed versus 61% of managers agreed: that senior management has implemented sufficient preventive measures to reduce occurrences of harassment and violence in the workplace. There is a discrepancy in how these groups view the agency's efforts to prevent harassment.

Workplace assessment

50. In order to prevent workplace harassment and violence incidents, the regulations require the agency to develop a workplace assessment, Footnote 12 which is the identification of risk factors, internal and external, in the workplace that may contribute to risks (including harassment and violence), an assessment of those risks, and the implementation of preventive measures to address the risks.

51. The agency's Occupational Health and Safety Program (OHS) and the Policy Health and Safety Committee (PHSC) collaboratively identified preliminary risks that could contribute to workplace harassment and violence. These risks were documented in Appendix B of the CBSA WHVP policy.

However, additional work is needed to identify interpersonal risk factors amongst colleagues and/or psychological risks.

Additionally, the likelihood and impact of these risks have not been assessed and preventive measures to mitigate the risks have not been identified.

52. We observed there was a lack of clarity in the CBSA WHVP Policy regarding the roles and responsibilities for the development of the workplace assessment because during early stages of this audit, OHS and NICE were unclear who was responsible for the assessment.

53. OHS, through its Hazard Prevention Plan, completes Job Hazard Analyses, where it identifies and assesses some harassment related risks and hazards. Through the job hazard analyses, the agency implements controls to protect employees against these hazards, and provide the necessary training and guidance to employees exposed to those hazards.

Given the interrelated nature of the work done by NICE and OHS, there is opportunity to collaborate using the existing hazard prevention plan to meet the harassment prevention requirements.

54. Additionally, the agency has access to data sourcesFootnote 13 where information related to harassment and violence is available, for example: PSES results, internal pulse checks/culture surveys, wellness scorecards, harassment and violence complaints received, etc. This information could be leveraged to inform risks or the effectiveness of preventive measures in the development of the workplace assessment.

Without effectively using available harassment and violence related data, the agency may not be able to proactively identify hotspots in its workplace and implement preventive measures.

How employees and management feel about existing preventive measures

55. The new regulations requiring that if an employee requests an investigation it must be undertaken have resulted in an increase in case load of approximately 60% since . Previously, an assessment would have been undertaken to determine whether an investigation was warranted. NICE resources have been prioritized to develop a new resolution process and respond to approximately 150 complaintsFootnote 14. As a result, NICE has not focussed on prevention.

56. However, governance records and communications via CBSA intranet and internal emails show that the agency is taking preventive actions to reinforce a zero tolerance policy on harassment and violence through its various strategies and initiativesFootnote 15.

More than half of the managers (62%) who responded to the survey agreed that agency management has been committed to efforts in promoting a harassment free workplace.

57. Despite the agency's efforts, 51% of employees who responded to the survey have expressed negative satisfaction with senior management's commitment to promoting a workplace free of harassment and violence.

The agency should create more awareness and continue to promote its initiatives to employees.

Fear of reprisal

58. 296 (45%) of respondents shared they have either been a victim or a witness of workplace harassment or violence between to . However, only 24 (8%) of these submitted a complaint to NICE. The rationale most frequently provided for not submitting a formal complaint included:

- not believing it would make a difference

- fear of reprisal

- not believing the incident would be kept confidential

59. Our observations related to reprisal are consistent with OAG’s Respect in the Workplace audit, which identified that agency employees had “serious or significant concerns about organizational culture, and that they feared reprisal if they made complaints of harassment, discrimination, or workplace violence violence…”

60. The agency’s 2020 PSES resultsFootnote 16, also highlighted that 55% of employees who faced harassment and did not file a complaint or grievance, did not do so due to a fear of reprisal. More than half of the respondents (56%) also expressed they didn’t feel senior management implemented measures to address concerns of reprisal.

61. In response to the OAG and PSES results, as well as the new regulations, the agency has created a confidential complaint disclosure procedure (through NICE)Footnote 17. Given that this process was recently developed, the full benefits associated with it may not yet have been realized. Additional promotion of the role of NICE and how it can help protect employees from reprisal, will help promote greater awareness of measures the agency has taken.

62. Without a process to assess risks related to harassment and violence in its workplace, the CBSA is less prepared to ensure that the correct preventive measures are in place to protect employees.

63. By preventing harassment from occurring and reducing the fear of reprisal, the agency can improve culture, morale, wellness and productivity; as well as decrease turnover and absenteeism rates.

Recommendation 2: The VP of HRB should ensure that a workplace assessment is completed as required by the regulations.

Management response: Agreed. The VP of HRB will engage the Policy Health and Safety Committee (PHSC) concerning the obligation for the agency and the applicable partners to jointly carry out a work place assessment and will ensure it is reviewed every three years.

Completion date:

Training

64. As of , CBSA employees are required to complete new mandatory harassment training based on their role, available through the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS). Three courses are available:

- WMT101 - Preventing Harassment and Violence in the Workplace for Employees: every CBSA employee must complete this course, no matter their position

- WMT102 - Preventing Harassment and Violence in the Workplace for Managers and Health and Safety Committees: CBSA employees who fall under the following categories must complete this course:

- have a direct report (supervisors, managers, executives)

- are a member of a Workplace Occupational Health and Safety Committee

- are an Occupational Health and Safety Representative

- WMT103 - Preventing Harassment and Violence in the Workplace for Designated Recipients: CBSA employees who work at NICE

Employees are required to retake the course(s), every three years.

65. We expected the agency has established and communicated mandatory training requirements, and monitors completion of each mandatory training course.

Sufficiency and tracking of training

66. Agency management and the unions agreed that the CSPS courses were sufficient to address the requirements under the regulations and as such, an in-house course was not developed. 82% of survey respondents found the CSPS training was relevant.

67. 80% of survey respondents found the CSPS training clearly outlined their roles and responsibilities related to preventing harassment and workplace violence. 67% of survey respondents found the CSPS training provided information on how to report an incident (WMT101 training). However, respondents suggested in addition to the CSPS training, the agency could supplement materials/tools with CBSA specific examples and/or context; including details on where to report an incident within the agency.

68. We reviewed the training courses and found they were relevant and addressed the requirements in the regulations.

69. We held focus groups with NICE advisors who indicated that dedicated training on having difficult conversations would help them better manage stressful discussions with their clients.

70. The completion of WMT101, the harassment course for all employees, is monitored and tracked by the Training and Development Directorate. As of , there was an 80.2% completion rate. The agency does not monitor and track training completion for managers and workplace occupational health and safety committee members (WMT102). A list of all job position titles (managers/supervisors) with direct reports and a list of employee names who are members of the committee were not available to track completion rates. NICE monitors completion of the training for its advisors (WMT103).

71. Given the importance of management in fostering a harassment free workplace, it is imperative they all receive the necessary training. Without being able to track and monitor training completion rates for managers, the agency is unaware of those who have not taken mandatory training.

Recommendation 3: The VP of HRB should strengthen the agency’s efforts in fostering a workplace culture free of harassment and violence by:

- developing and communicating harassment prevention and resolution awareness materials and tools

- identifying and promoting existing preventive measures, accountabilities and mechanisms to prevent reprisal to all CBSA employees

- monitoring the completion rate for WMT102 Manager training course

- empowering managers to take appropriate action to resolve conflict and incidents of workplace harassment and violence

Management response: Agreed. In the context of the agency’s broader framework for the development of a healthy & respectful workplace culture, free of harassment and violence, the VP of HRB will continue to support the agency’s efforts under the Respectful Workplace Framework and will clarify expectations of the WHVP program to guide the related service offering.

Completion date:

Resolution of harassment incidents

72. The regulations state that an employer must attempt to resolve all occurrences of harassment and violence of which they have been informed. This resolution process is driven by an employee (principal party) submitting a Notice of Occurrence. The regulations describe the steps of the resolution process, including expected timeframes that must be respected.

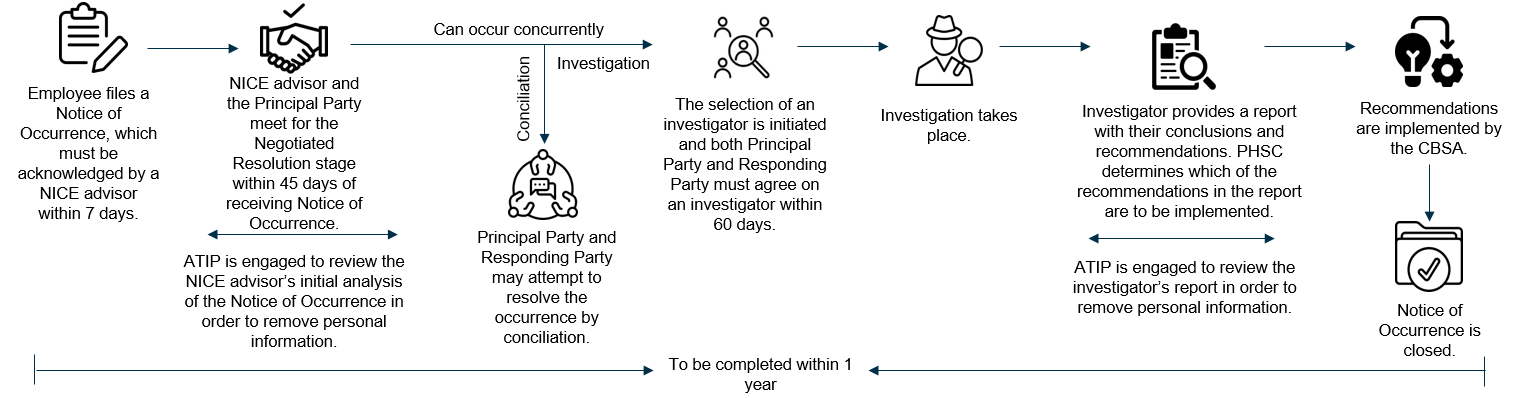

73. NICE centrally manages the intake and processing of a harassment and/or violence complaint received. The process involves several stakeholders including, management, Informal Conflict Management System (ICMS), procurement, security, Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP). The key stages of the resolution process are as follows (refer to Appendix C for more details on the resolution process):

Figure 1: Resolution process

Text description: Figure 1

Resolution process

The resolution process is fully described in the body of the content in Appendix C.

74. We expected the agency had designed a harassment complaint resolution process in alignment with the regulations, TBS directives and agency policies, and responded to occurrences in a timely manner.

Resolution process

75. NICE developed a resolution process flow chart that was available to all employees on the intranet.

76. 21 out of 24 (88%) survey respondents indicated there were gaps in the NICE resolution services. 59% of respondents who have accessed NICE services expressed the process to report an incident to NICE was not clear.

77. Some opportunities for improvement with NICE services raised by survey respondents were:

- Clarifying how the regulations define harassment and the final outcome of the NICE process. Some respondents expressed their Notice of Occurrence was not accepted since it did not meet the definition of harassment but did not understand why.

- Clearly explaining the other resolution mechanisms available (such as ICMS, conciliation, or negotiated resolution) to resolve a harassment complaint, other than an investigation. The other mechanisms may provide faster resolution for the parties involved.

- The regulations allow the principal party the flexibility to pursue multiple avenues of resolution. Conciliation and an investigation can occur concurrently. The regulations allow this in order to let the principal party determine which path(s) is most effective at reaching a resolution.

78. We reviewed four complaintsFootnote 18 to assess whether the agency’s complaint resolution process contained all key aspects of the regulations and the TBS Directive. We found that:

- the resolution process is mostly designed to align with the requirements in the regulations, TBS Directive and other applicable guidance

- the investigation steps contain elements of procedural fairness

- appropriate measures have been taken to ensure privacy and confidentiality of the occurrence and parties involved

- templates and tools are available for the purposes of conducting the resolution in a fair, consistent and objective manner

- NICE advisors provided monthly updates to the principal party

- 67% of respondents agreed they received regular updates on their case

79. In fiscal year 2022 to 2023, NICE prioritized streamlining the resolution process and explored the ability to use a risk based approach to managing cases. Some elements of process changes have been documented in the next section.

Timeframes

80. The regulations stipulate timeframes for specific stages of the resolution process. We analyzed harassment complaint data for all Notices of Occurrence received within the audit scope period and observed that the resolution process does not adhere with some timeframes. Specifically, the regulations require that:

- Notice of Occurrence be acknowledged within 7 days of receipt. Cases meeting: 86%

Negotiated resolution be attempted within 45 day. Cases meeting: 39%

We found many factors made it difficult for NICE to conduct the initial meeting for negotiated resolution within the 45 days. The main reasons were:

- the principal party went on extended leave due to personal reasons

- due to factors such as caseload, NICE advisors did not schedule meetings with the principal party in a timely manner

- ATIP did not review the Notice of Occurrence within their service standards causing delays

Selecting an investigator within 60 days. Cases meeting: 69%

The 32 active cases that exceeded the one year requirement were in the investigation stage (largest amount of cases at any stage). This was because:

- A qualified list of investigators was not established as allowed by the regulations. Instead, NICE selected investigators from the existing PSPC standing offerFootnote 19. Developing a dedicated list could help speed up the selection and procurement of a qualified investigator.

- CBSA’s procurement processes required that NICE wait until security clearances for an investigator were re-verified. However, CBSA Procurement and Security has recently issued a new directiveFootnote 20, which is expected to expedite the selection of an investigator.

- Notice of Occurrence must be closed within 1 year: cases meeting: 64%

- Challenges in holding a negotiated resolution meeting and delays with selecting an investigator have impacted the agency’s ability to complete a Notice of Occurrence within a year.

- While this is not required by the regulations, ATIP would review both a preliminary investigation report and the final investigation report to ensure proper vetting. Due to capacity and other priorities within ATIP, NICE faced delays receiving completed ATIP reviews in a timely manner.

- In summer 2022, NICE has streamlined this process by requiring only the final investigation report to undergo ATIP review. Removing unnecessary review within the process will help accelerate timelines.

81. We also observed that some experienced NICE advisors may manage upwards of 20 cases at any given time, which they explained may contribute to delays with meeting mandated timelines. Additionally, some advisors expressed feeling overworked and burnt out due to the case volumes.

82. It is important to note that some challenges – i.e. if principal party goes on extended leave - are not within NICE’s control and as such may continue to impact their ability to meet the one year timeline for closing a Notice of Occurrence.

- As stipulated in the regulationsFootnote 21, NICE maintains the rationale for delays within their files.

83. 79% of survey respondents who have accessed services offered by NICE expressed their case is (or was) not handled in a timely manner.

84. Challenges and delays may reduce the employees’ confidence in the resolution process, and may impact their morale and productivity.

85. Additionally, delays will impact the agency’s ability to implement corrective measures and restore the work environment.

86. Unaddressed harassment incidents in the workplace are damaging to the agency’s workplace culture and its reputation and can also result in additional costs due to potential lawsuits or sanctions from the Labour program.

Recommendation 4: The VP of HRB should improve the resolution process by:

- Addressing the bottlenecks and delays in the process to ensure it is aligned with the timeline requirements included in the regulations; and

- Providing the appropriate support to advisors to better equip them to have difficult conversations with clients.

Management response: Agreed. The VP of HRB will take action to improve the efficiency of the WHVP resolution process to ensure the agency’s compliance with the legislated timelines (section 15 to 34 of the regulations) and foster early resolution.

The VP of HRB will also explore/leverage innovative learning opportunities, business models and work organization to better support advisors managing cases, promote expertise development and improve staff retention.

Completion date:

Conclusion

87. The agency has taken steps to address most of the requirements under the regulations related to the prevention of harassment and violence in the workplace for example by designing a resolution process for reporting harassment incidents.

88. While progress has been made, opportunities exist to further improve how the agency promotes its efforts in fostering a respectful workplace and ensuring it is fully compliant with the regulations. These include:

- promoting the existing preventive measures and other procedures in place, such as the anonymous procedures to report harassment incidents, so more employees are aware they can report harassment without the fear of reprisal

- completing a workplace assessment in order to have a full picture of all harassment risks and to understand where additional preventive measures may be needed

- addressing challenges in the resolution process that cause delays in meeting required timeframes

89. Overall, the agency should ensure the outcome of its actions yield positive results that showcase to the employees, the agency’s commitment to building a healthy, respectful and safe workplace.

Page details

- Date modified: