Canadian Red Cross

Immigration Detention Monitoring Program (IDMP)

Annual Monitoring Activity Report

Monitoring Period 2019-2020

This document is also available in PDF (838 KB)

Contents

List of Abbreviations

- ATD

- Alternatives to Detention

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CRCS

- Canadian Red Cross Society

- DLO

- Detention Liaison Officer

- GTA

- Greater Toronto Area

- IDMP

- Immigration Detention Monitoring Program

- IHC

- Immigration Holding Centre

- IRPA

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- NGO

- Non-Governmental Organization

- PCF

- Provincial Correctionnal Facility

- UNHCR

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Executive Summary

Within the Canadian Red Cross Society (CRCS), detention monitoring is administered by the Immigration Detention Monitoring Program (IDMP) in accordance with the Contract between the CRCS and the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) encompassing the extended contract period from June 28, 2017 to July 15, 2020, inclusive.

Pursuant to this agreement, CRCS monitoring activities focus on the following areas of detention of people under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA):

- The treatment by facility staff, contractors and other detainees;

- The conditions of detention – the state of the detention environment (e.g. facility, lighting, food, recreation, well-being of detainees in that environment);

- The legal guarantees and procedural safeguards – ability to exercise their human rights, access to procedural safeguards (e.g. the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, effective legal remedies, protection from arbitrary detention); and

- The ability to contact and maintain contact with family.

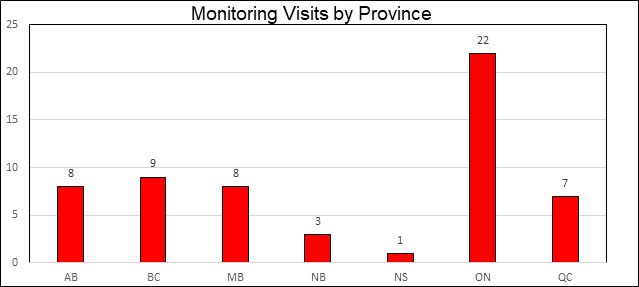

This report highlights the observations and recommendations of the CRCS following a total of fifty one (51) planned visits and seven (7) visits in response to notifications to twenty-five (25) detention facilities holding persons detained under the IRPA between April 2019 and March 2020. Findings, observations and recommendations are grouped into the following six themes:

- Treatment: impact of co-mingling in provincial correctional facilities (PCFs);

- Conditions of detention: detention of vulnerable persons and people in long-term detention;

- Conditions of detention: access to healthcare, including mental health care services;

- Conditions of detention: religious, cultural, educational and leisure activities;

- Legal guarantees and procedural safeguards: access to information; and

- Family contact.

Based on findings and observations, the CRCS makes the following main recommendations to the CBSA within this report:

- Further expand the availability of alternatives to detention (ATDs) and offer ATDs adapted to a larger variety of specialized needs;

- Facilitate voluntary transfers of detained individuals from PCFs to immigration holding centres (IHCs), including across provinces or regions, considering proximity to family;

- Avoid placing vulnerable persons in detention; when detention under the IRPA is deemed necessary, to the maximum extent avoid using PCFs to hold vulnerable people;

- Ensure that persons detained under the IRPA have access to adequate health care, including mental health care services, regardless of their place of detention;

- Ensure that people detained for immigration reasons have access to leisure, cultural and educational activities regardless of their place of detention;

- Ensure that persons detained under the IRPA have adequate access to information; including to interpretation services;

- And finally, allow regular and meaningful contact between detained individuals and their families and friends.

Introduction

The CRCS provides independent monitoring of detention under the IRPA to promote a protective environment in which people detained for immigration reasons are treated humanely and where their human rights and inherent dignity are respected, in accordance with international and domestic standards. During visits to places of detention, the CRCS monitors and assesses the conditions of detention and treatment of people, held administratively under the IRPA in federal government-run IHCs, detention facilities under the management of provincial authorities, or other municipal correctional facilities Footnote 1. In accordance with an agreement between the CRCS and the CBSA, this report reflects CRCS Immigration Detention Monitoring Program activities carried out between April 2019 and March 2020.

A total of fifty eight (58) site visits were conducted during the monitoring period, including those in response to a notification of an event, involving a person detained under the IRPA. The CRCS acknowledges CBSA representatives and staff in the visited facilities for facilitating access to individuals detained therein.

On March 11, 2020 the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic and it remains an emergency of international concern. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, COVID-19 poses a serious health threat to people in Canada, with the situation continuing to evolve daily. The CRCS acknowledges that preventative measures to limit the potential spread of COVID - 19 in detention facilities are necessary; however, some of these measures have the potential to impact the ability to meet the minimum standards for people being held under administrative detention. Since the reporting period for this document ended on 31st March 2020, the CRCS did not have enough time to obtain a broad understanding of the measures being taken to prevent and respond to COVID-19 cases in immigration detention, nor the impact of these measures on detained people for the period reported. Therefore, findings and recommendations on this subject will not be included in this report.

During visits to places of detention, the CRCS took a system-wide approach focussing on four assessment categories:

- 1. Treatment

- 2. Conditions of detention

- 3. Legal guarantees and procedural safeguards, and

- 4. Family contact

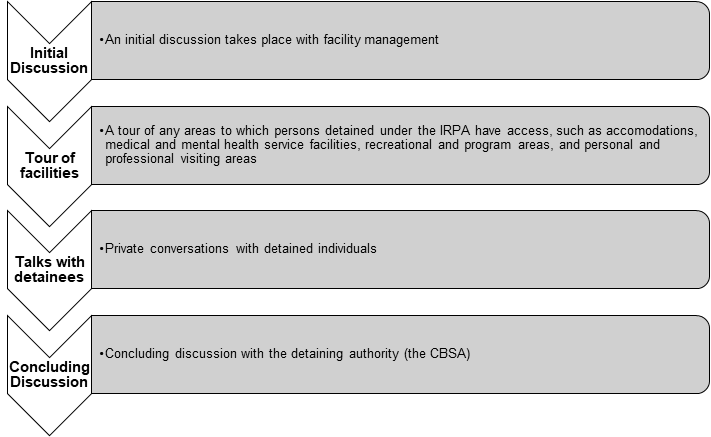

Visits follow a standard procedure that includes the following steps:

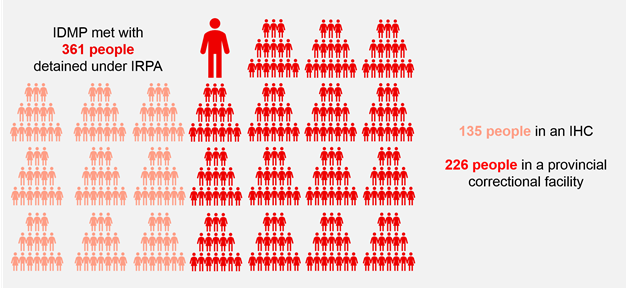

Over the course of the reporting period, the CRCS team conducted 361 interviews with individuals detained under the IRPA in IHCs and PCFs, with the highest number of interviews taking place in Ontario, followed by Quebec, British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

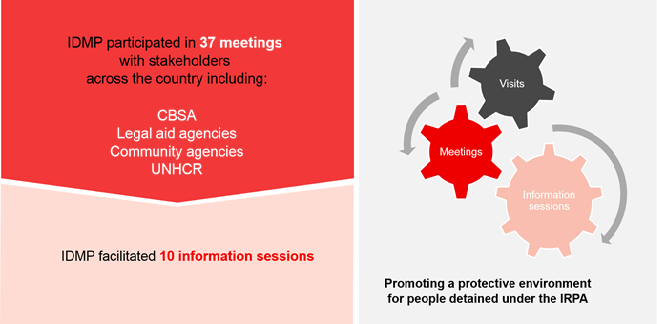

During the reporting period and in order to promote a protective environment for people detained under the IRPA, the CRCS carried out 10 information sessions on its mandate for the detaining authority staff and personnel in direct contact with persons detained under the IRPA. Moreover, the CRCS held 37 meetings with stakeholders, including regional CBSA representatives, personnel of provincial correctional services, United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), provincial legal aid agencies and local NGOs supporting persons detained under the IRPA.

Main Findings

Following CRCS IDMP activities carried out between April 2019 and March 2020, the CRCS highlights the following findings and recommendations Footnote 2:

I. Co-mingling in provincial correctional facilities.

In line with its administrative nature, detention for immigration reasons must not be punitive. The use of correctional facilities, including but not limited to prisons, jails, and facilities designed or operated as prisons or jails, should be avoided since these environments expose people detained for administrative reasons to policies and procedures designed to manage people within the criminal justice system. Given the administrative nature of immigration detention, people detained under the IRPA and held in correctional facilities should be separated from people who are being held under the Criminal Code – which is a well established principle under international law. Conditions of their detention should be minimally restrictive and non-punitive, and they should be subject to treatment and conditions in line with the administrative nature of their detention Footnote 3.

During the period under review, nearly 2000 people detained for immigration reasons were held in provincial correctional facilities Footnote 4. In all but one correctional facility visited, co-mingling between people detained under the IRPA and those detained under the Criminal Code – whether at the cell-level or the unit-level – continued to be a common practice. The following consequences of co-mingling on individuals detained under the IRPA were observed:

- Being subject to procedures designed for people held under the Criminal Code, such as strip-searches and disciplinary measures; being subject to lockdowns and placement in units with very restrictive conditions, such as high security or segregation units, which are not appropriate for people in administrative detention, resulting in limited time outside their cells, reduced and irregular access to open air, telephones, showers and other basic services;

- Being witness or subject to threats and physical violence and feeling unsafe and frustrated for being held in a criminal facility when they are not currently held under the Criminal Code;

- Placement of more people in a cell than what it is designed to hold (triple bunking in a cell designed for two or double bunking in a cell for one), also noting that efforts were made in some facilities to reduce the length and the frequency of the practice.

Nonetheless, with the implementation of the National Immigration Detention Framework, the CRCS acknowledges that the CBSA is taking concrete steps to reduce its reliance on PCFs, such as:

- The opening of an enhanced security area in the Toronto IHC which can accommodate 20 males and eight females with more complex profiles who would otherwise be held in a PCF;

- The continued practice of holding people detained for immigration reasons with more complex profiles in the Laval IHC, reducing the numbers of those held in a PCF;

- Finally, the opening of a new IHC in Surrey, British Colombia, which, coupled with broader use of ATDs and continued use of a dedicated unit in Fraser Regional Correctional Centre, represents an opportunity to end the practice of co-mingling in the Pacific Region.

To further CBSA efforts, the CRCS recommends the following:

- (i) Further expanding the availability of specialized ATDs which are equipped to respond to a larger variety of specialized needs of migrants Footnote 5;

- (ii) Facilitating voluntary transfers of detained individuals from PCFs to IHCs, including across provinces or regions, and considering proximity to family (in cooperation with other authorities involved such as IRB and criminal courts);

- (iii) Continue to improve the detention placement assessment process determining if a person with a criminal past is eligible to be placed in an IHC, taking into account all available factors that can lead to a more precise assessment of their current behavior and level of risk Footnote 6.

Finally, the CRCS recommends that the CBSA, in all instances where it places a person in a PCF, ensure the individual is held in a specialized unit where they are entirely separated from the population being held under the Criminal Code, while also avoiding situations of solitary confinement to achieve that separation. In addition, conditions in these units, as well as access to activities and services, must meet the minimum standards for people held under administrative detention.

II. Detention of vulnerable people and people in long-term detention.

Responding to the needs of vulnerable people is at the core of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement’s mandate. All individuals placed in detention face some level of vulnerability since they depend on the detaining authority to respond to their basic needs. The CRCS believes that the detention of the most vulnerable persons Footnote 7 should be avoided since it can have serious negative effects on their physical and mental health Footnote 8. Moreover, in all cases of detention for immigration reasons, the length of detention should be limited in time and the decision to detain should be re-evaluated regularly. Considerations should include the necessity, reasonableness and proportionality of detention taking into account the cumulative negative effect on the individual’s wellbeing and, when applicable, the best interests of directly impacted children Footnote 9.

The CRCS acknowledges the efforts made by the CBSA in addressing the detention of vulnerable people, including the roll-out of Community Case Management and Supervision program. Nonetheless, the CRCS continued to observe vulnerable individuals in immigration detention in all regions, including people with mental health issues; people fleeing conflict and other situations of violence; those at risk of violence due to their gender, sexual orientation or gender identity; and others. These individuals are at a higher risk of suffering a serious negative impact in detention. In addition, some of these individuals were detained in provincial correctional facilities.

The CRCS also observed that children – including of nursing age – continued to be present in immigration detention, notably in the Laval IHC, which has a detrimental impact on their wellbeing. The CRCS recognizes the efforts made by the facility staff to respond to the needs of those children, but reiterates that given their level of vulnerability and their developmental needs, it is not in the best interest of the child to be placed in a detention facility. In an overwhelming majority of cases, family unity outside detention would be in the child’s best interest Footnote 10.

The CRCS acknowledges that the average and median length of detention have been reduced; moreover, the number of individuals detained for more than 99 days has steadily decreased in recent years Footnote 11. However, during its visits, the CRCS IDMP continued observing individuals detained for immigration reasons for several months, even years. Some of those detained for these long periods of time had additional vulnerabilities, such as requiring mental health support, and they feared the negative effects of their detention would continue after they were no longer detained. Also, some individuals detained for long periods of time mentioned their relationships and links to the community had been severed.

The CRCS encourages the CBSA to further expand the availability of ATDs in all regions to be able to offer them to a greater number of vulnerable individuals. As well, it is recommended to offer ATDs adapted to a greater diversity of people with specialized needs, such as ATDs offered by organizations with expertise in providing trauma-informed medical and mental health care – considering that such an investment will permit detaining authorities to safeguard the wellbeing of eligible individuals. Among others, the CRCS recommends investing in the further development of ATDs for families with children, in order to maintain family unity outside detention; individuals with physical and mental health needs, including continued care outside detention; and individuals whose detention is long-term.

The CRCS recommends that people detained under the IRPA be provided with information to better understand the avenues available to them in pursuing ATDs, both through the CBSA ATD programs and through other avenues.

The CRCS considers the use of PCFs to hold people in immigration detention, and especially the most vulnerable, to be problematic and that it should be avoided. In addition to the reasons outlined above, the CRCS also notes that the resources required to identify and perform ongoing evaluations of vulnerable persons’ unique needs were limited in the visited PCFs, including reduced interaction with CBSA officers. Moreover, the PCFs visited by the CRCS offer limited care and support to people detained under the IRPA who have specialized needs, such as individuals with prior trauma or those requiring mental health support.

III. Access to healthcare.

Detention can damage a person’s overall wellbeing and exacerbate existing mental and physical health issues. Accordingly, when detention under the IRPA is deemed necessary, detained individuals should receive a medical examination by a qualified healthcare professional as soon as possible following their admission, as well as regular medical treatment and services throughout their detention Footnote 12. Full access to the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP) or an equivalent program is essential regardless of the place of detention.

The CRCS recognizes the CBSA’s willingness to address issues related to the provision of healthcare during detention at IHCs: people detained herein expressed having timely access to the IFHP and its supplemental coverage, including mental health services and support.

However, access to healthcare for people held for immigration reasons in PCFs varied greatly from one institution to another. In our observation, access to health care was dependant on provincial coverage; the capacity to access services covered by the IFHP supplemental coverage; visits by CBSA detention liaison officers (DLOs) or officers with DLO-like functions, who help detained people access health care services; and structural issues such as understaffing in the facilities and high turnover of medical personnel. In many PCFs, specialized mental health care was particularly difficult to obtain and the services available were often limited to crisis intervention. In some provincial correctional facilities, individuals with mental health needs were placed in a segregation unit which does not respond to the underlying needs and poses the risks of exacerbating their mental health condition due to isolation, highly restricted movement and limited access to services and social interaction.

Medical examinations by qualified medical personnel at admission were not provided in one of the provincial correctional facilities visited, which created a public health risk and also led to interruptions of treatment.

The CRCS recommends that the CBSA, regardless of the place of detention, provides people detained under the IRPA with full and timely access to the services covered by the IFHP or equivalent coverage. Special attention should be given to the most vulnerable individuals, including those diagnosed with mental health conditions and those who have declared a need for mental health support. Moreover, it would be important to consider extending this coverage to people under ATDs.

IV. Conditions of Detention: religious, cultural, educational and leisure activities.

The absence of purposeful activity is a damaging aspect of detention, it increases hopelessness, and has significant negative impacts on a person’s wellbeing; these impacts are exacerbated when the detention is prolonged. Under international law Footnote 13, detained individuals should have the right to activity and leisure, as well as access to educational programs, respecting the non-criminal status of people in immigration detention.

During the period in review, some detained individuals at IHCs and PCF reported having access to activities, while others held in some PCFs visited reported not having enough information about how to access activities or not being eligible given their status, as most programs are reserved for convicted individuals.

The CRCS recommends that the CBSA ensures people detained for immigration reasons have access to leisure, cultural and educational activities regardless of their place of detention. Access to such activities are highly encouraged in a detention context as they are important for an individual’s wellbeing, including personal development, physical and mental health, and social and cultural inclusion. Moreover, they can contribute to reducing the negative effects of detention by relieving stress and promoting positive interactions with others.

V. Access to information.

People detained under the IRPA should be able to obtain information related to their administrative process and their rights, such as the right to legal representation. Upon admission, individuals detained for immigration reasons should be provided with information on the place of detention where they are held, available activities and services and how to access them Footnote 14. This includes information on medical care; complaint mechanisms; policies on the use of phones and how to request mobile or international calls; procedures and schedules for family visits, as well as the rules and disciplinary measures in the holding facility. When needed, a qualified and impartial interpreter should convey this information and be readily available at key moments during the immigration detention process Footnote 15.

The level of information that people detained under the IRPA possessed depended on the region in which they were held, the type of facility and the frequency of contact with CBSA personnel. Transmission of information to individuals detained at IHCs was facilitated by the constant presence of CBSA officers permitting a regular and direct contact between the CBSA and the people detained.

In provincial correctional facilities, the sharing of information varied greatly. People held in correctional facilities who were regularly visited by CBSA staff, such as DLOs, tended to have the basic information they required. Moreover, the development of facility specific documentation in certain regions, such as in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), greatly helped the provision of information on obtaining services. However, individuals in PCFs who had not had the opportunity to meet with DLOs or other CBSA officers with similar functions reported having difficulty accessing services such as medical care, overseas calls and calls to mobile phones; in some cases they were not aware that certain services were available to them.

Depending on the facility, professional interpretation services were not always available for people detained who were not proficient in the language the interactions were conducted. Lack of interpretation was frequently reported, for example, during medical examinations and the admission process.

The CRCS understands the CBSA intends to supplement the briefing material package for people detained under the IRPA. Considering that various factors, including literacy and stress, impact the capacity of a detained person to absorb information, the CRCS recommends complementing the existing system with additional means of sharing information in various languages and formats. This should include having verbal, written or recorded audiovisual materials readily available or presented regularly.

The CRCS strongly urges the use of professional interpretation services during key moments of detention, including facility orientations, and particularly for medical or mental health consultations or any other interaction of a confidential or decisive nature. Unit staff in provincial correctional facilities should have access to interpretation services, such as a service available by phone, for day-to-day communication with people detained under the IRPA.

Given the support DLOs can offer, and recognizing on-going CBSA efforts in the matter, the CRCS recommends to continue expanding the implementation of the initial meeting with these officers, or other officers carrying out DLO functions, as well as holding regular meetings throughout detention with all people detained under the IRPA and held in provincial institutions, regardless of whether they had previous interaction with other CBSA officers.

VI. Ability to contact and maintain contact with family.

People detained for immigration reasons must be allowed contact with family and friends on a regular basis, regardless of where they are being held. Contact can be in the form of verbal and written communication and in-person visits. This right is guaranteed under international and national legal frameworks Footnote 16. Regular, meaningful contact contributes to reducing the stress of family separation and the impact of detention. It also helps individuals gather the documents required to regularize their immigration status or prepare for their removal from the country.

Telephones in IHCs are accessible and permit free local calls and calls to mobile phones. Long distance national calls and international calls are also possible with calling cards available for purchase; however, international calls can be very expensive. For people not being able to afford calling cards, the CBSA facilitates exceptional free national long distance calls and international calls or, in the case of the Laval IHC, a local NGO offers free calling cards to individuals with less resources.

The CRCS IDMP observed that maintaining family contact in PCFs was more complicated, barriers included:

- Limits on the types of calls permitted within the facility (e.g. only collect calls to landlines);

- The cost of calls - international calls being particularly expensive or even not possible to most countries from the phones in the living units in some facilities;

- Automated phone services in a language not spoken by the caller or the recipient;

- Automatic call cut off after 15/20 minutes depending on the province;

- Dynamics inherent to criminal detention hampering access to the telephones in the units; and

- Limited time out of cells in high security and segregation units affecting detained people’s ability to access telephones.

The CRCS acknowledges the work that the CBSA has undertaken to address gaps restricting detained people’s ability to maintain contact with their family. In certain GTA provincial correctional facilities, the CBSA has put in place measures such as bringing a cellphone inside the facility to offer calls to people held under the IRPA, or having a CBSA staff member permanently present in the correctional facility offering free telephone calls to people detained for immigration reasons. Moreover, some correctional facilities can support making calls through social workers or the chaplaincy, although the process is not always widely known, and calls are not offered systematically.

In-person contact visits were allowed at the Laval IHC. The renovated Toronto IHC and the new IHC in Surrey both have infrastructure permitting these types of visits, however the extent of their availability was not defined when the present report was being drafted. Contact visits for people held under the IRPA were not allowed in all the PCFs visited by the IDMP. The CBSA facilitated contact visits with family members during in-person hearings, but these were offered at the CBSA’s discretion and were not regular.

The CRCS recommends that the CBSA considers solutions to allow all people detained under the IRPA, regardless of the facility in which they are held, to maintain regular contact with family and friends, taking advantage of new technologies when possible, while putting in place adequate measures to protect confidentiality. This includes making local, long-distance and international calls to landlines and mobile phones. The CRCS also recommends that people detained under the IRPA be adequately informed of available opportunities to communicate with family and friends.

While long term solutions are being developed, the CRCS encourages the CBSA to continue working with PCFs to implement interim solutions to problems related to phone calls.

Finally, contact visits, particularly in instances where family separation has resulted from a parent or guardian being detained under the IRPA, should be made possible on a regular basis, regardless of a person’s place of detention, and when applicable, in accordance with the best interests of the impacted children.

Conclusion

The CRCS is an independent, neutral and impartial humanitarian organization. Its mandate, defined in Canadian law and in the Statutes of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, is to prevent and alleviate human suffering. The CRCS methods in detention monitoring are based on best practises and processes of the International Committee of the Red Cross, who have been working to secure humane treatment and conditions of detention for people deprived of their liberty for over a century. As part of the Movement-wide response to humanitarian consequences caused by migration, the CRCS started detention monitoring activities in 1999 and acts according to its fundamental principles, providing unbiased observations and recommendations to the Canadian authorities with the aim to safeguard rights and improve the conditions of detention for people detained under the IRPA.

CRCS detention monitoring is administered by the IDMP in accordance with the Contract between the CRCS and the CBSA encompassing the period from June 28, 2017 to July 15, 2019 and extended to July 15, 2020 inclusive. This report presents the CRCS observations and recommendations on immigration detention following 58 visits to 25 facilities between April 2019 and March 2020.

Both the findings and the recommendations made in this report are aimed at improving the conditions of detention for people detained for immigration reasons in a number of areas, including but not limited to:

- Treatment: impact of co-mingling in PCFs;

- Conditions of detention: detention of vulnerable persons and people in long-term detention;

- Conditions of detention: access to healthcare, including mental health care services;

- Conditions of detention: religious, cultural, educational and leisure activities;

- Legal guarantees and procedural safeguards: access to information; and

- Family contact.

Based on findings and observations from CRCS IDMP activities carried out between April 2019 and March 2020, the CRCS makes the following main recommendations:

- Further expand the availability of ATDs and offer ATDs adapted to a larger variety of specialized needs;

- Facilitate voluntary transfers of detained individuals from PCFs to IHCs, including across provinces or regions, considering proximity to family;

- Avoid placing vulnerable persons in detention; when detention under the IRPA is deemed necessary, to the maximum extent avoid using PCFs to hold vulnerable people;

- Ensure that persons detained under the IRPA have access to adequate health care, including mental health care services, regardless of their place of detention;

- Ensure that people detained for immigration reasons have access to leisure, cultural and educational activities regardless of their place of detention;

- Ensure that persons detained under the IRPA have adequate access to information; including to interpretation services;

- And finally, allow regular and meaningful contact between detainees and their families and friends.

The CRCS stands ready to discuss the findings made in this report with the CBSA and to provide objective feedback and advice on how to increase the protective environment within immigration detention in Canada.

Relevant standards

- ATP

- United Nations (UN) Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Anti-Trafficking Protocol) (2000)

- ACHR AP

- Organization of American States (OAS) American Convention on Human Rights Additional Protocol in the area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1988)

- BPP

- UN Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (1988)

- BR

- UN Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the “Bangkok Rules”) (2010)

- CMW

- UN Convention for the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (1990)

- CRC

- UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989)

- GCM

- Global Compact For Safe, Orderly And Regular Migration (2018)

- GCR

- Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Part II: Global compact on refugees (2018)

- ICCPR

- UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966)

- PBPPDLA

- OAS/Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) Principles and Best Practices on the Protection of Persons Deprived of Liberty in the Americas (2008)

- RPJDL

- UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (1990)

- SMR

- UN General Assembly, UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules): resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 8 January 2016, A/RES/70/175

- UNHCR-DG

- UNHCR Guidelines on the Applicable Criteria and Standards relating to the Detention of Asylum-Seekers and Alternatives to Detention (2012)

- Date modified: