Statement of reasons—Expiry review determination: Carbon Steel Welded Pipe (CSWP1 2024 ER)

Concerning an expiry review determination under paragraph 76.03(7)(a) of the Special Import Measures Act respecting carbon steel welded pipe originating in or exported from China.

Decision

Ottawa,

On July 18, 2024 pursuant to paragraph 76.03(7)(a) of the Special Import Measures Act, the Canada Border Services Agency determined that the expiry of the Canadian International Trade Tribunal’s order made on March 28, 2019, in Expiry Review No. RR-2018-001:

- is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of dumping of such goods originating in or exported from China and

- is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of subsidizing of such goods originating in or exported from China

On this page

Executive summary

[1] On February 19, 2024, the Canadian International Trade Tribunal (CITT), pursuant to subsection 76.03(3) of the Special Import Measures Act (SIMA), initiated an expiry review of its order made on March 28, 2019, in Expiry Review No. RR-2018-001, concerning the dumping and subsidizing of carbon steel welded pipe (CSWP) originating in or exported from the People’s Republic of China (China).

[2] As a result of the CITT’s notice of expiry review, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), on February 20, 2024, initiated an investigation to determine, pursuant to paragraph 76.03(7)(a) of SIMA, whether the expiry of the order is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of dumping and/or subsidizing of the goods.

[3] The CBSA received responses to the Canadian producer expiry review questionnaire (ERQ) from Welded Tube of Canada Corporation (Welded Tube)Footnote 1, Evraz Inc. NA Canada (Evraz)Footnote 2, Atlas Tube Canada ULC (Atlas)Footnote 3, DFI Corporation (DFI)Footnote 4, and Nova (collective response from Nova Tube Inc. (Nova Tube) and Nova Steel Inc. (Nova Steel))Footnote 5. The submissions made by Atlas, DFI, and Nova expressed an opinion that the continued or resumed dumping and subsidizing of CSWP from China is likely if the CITT’s order expires.

[4] The CBSA received a response to the Canadian importer ERQ from Forest City Models and Patterns Limited (Forest City)Footnote 6, a plastic molding manufacturer located in Thorndale, ON.

[5] The CBSA did not receive any responses to the exporter ERQ or the foreign government ERQ.

[6] Nova and DFI both provided a case brief to the CBSA in support of their position that continued or resumed dumping and subsidizing of CSWP from China is likely if the CITT’s orders expires.Footnote 7 Atlas did not submit case briefs, and instead provided a letter of concurrence where they supported the continuation of the CITT’s order.Footnote 8 No other party provided a case brief to the CBSA and no party provided a reply submission in response to Nova’s or DFI’s case brief.

[7] The analysis of information on the administrative record indicates a likelihood of continued or resumed dumping into Canada of CSWP from China should the CITT’s order expire. This analysis relied upon the following factors:

- Commodity Nature of CSWP

- Global Steel and Welded Pipe Market Conditions

- Economic Outlook in China

- Excess Production Capacity of Steel and CSWP in China

- Attractive Canadian Market

- Inability of Chinese Exporters to Sell to Canada at Non-dumped Prices While the CITT Order was in Effect

- Imposition of Anti-dumping Measures by Authorities of Jurisdictions other than Canada concerning Welded Pipe from China

- China’s Proclivity to Dump Steel Products

[8] The analysis of information on the administrative record indicates a likelihood of continued or resumed subsidizing into Canada of CSWP from China should the CITT’s order expire. This analysis relied upon the following factors:

- Imposition of Countervailing Measures on Other Pipe, Tube and Steel Products from China by Canada

- Imposition of Countervailing Measures concerning CSWP from Jurisdictions Other than Canada

- Continued Availability of Subsidy Programs for CSWP Producers/Exporters in China

[9] For the foregoing factors, the CBSA, having considered the relevant information on the record, determined on July 18, 2024, pursuant to paragraph 76.03(7)(a) of SIMA that the expiry of the order in respect of CSWP is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of dumping and subsidizing of the goods from China.

Background

[10] On January 23, 2008, following a complaint filed by ArcelorMittal/Mittal Canada Inc., the CBSA initiated investigations pursuant to subsection 31(1) of SIMA, into the alleged dumping and subsidizing of CSWP originating in or exported from China.

[11] On July 21, 2008, pursuant to subsection 41(1) of SIMA, the CBSA made final determinations respecting the dumping and subsidizing of CSWP originating in or exported from China.

[12] On August 20, 2008, pursuant to subsection 43(1) of SIMA, the CITT found that the dumping and subsidizing of CSWP originating in or exported from China had caused injury to the domestic industry in Canada.

[13] On February 14, 2011, the CBSA concluded a re-investigation to update the normal values, export prices and amounts of subsidy in respect of CSWP originating in or exported from China.

[14] On August 19, 2013, the CITT determined that the expiry of its finding would cause material injury to the domestic industry. Therefore, the CITT continued its finding made in Inquiry No. NQ-2008-001.

[15] On March 28, 2019, the CITT determined that the expiry of its order would cause material injury to the domestic industry. Therefore, the CITT continued its order made in Expiry Review No. NQ-2018-001.

[16] On February 19, 2024, the CITT initiated an expiry review of it’s order pursuant to subsection 76.03(3) of SIMA.

[17] On February 20, 2024, the CBSA initiated an expiry review investigation to determine whether the expiry of the order is likely to result in continued or resumed dumping and/or subsidizing of the subject goods.

Product definition

[18] For purposes of this expiry review investigation “CSWP” is defined as:

Exclusions

- carbon steel welded pipe in nominal pipe sizes of 1 inch, meeting the requirements of specification ASTM A53, Grade B, Schedule 10, with a black or galvanized finish, and with plain ends, for use in fire protection applications

- carbon steel welded pipe in nominal pipe sizes of ½ inch to 2 inches inclusive, produced using the electric resistance welding process and meeting the requirements of specification ASTM A53, Grade A, for use in the production of carbon steel pipe nipples and

- carbon steel welded pipe in nominal pipe sizes of ½ inch to 6 inches inclusive, dual-stencilled to meet the requirements of both specification ASTM A252, Grades 1 to 3, and specification API 5L, with bevelled ends and in random lengths, for use as foundation piles

[19] For purposes of this expiry review investigation, CSWP also refers to goods produced in Canada that meet the above product definition.

Additional product information

[20] CSWP, also commonly referred to as standard pipe, covers a wide range of pipe products generally used in plumbing and heating applications for the low-pressure conveyance of water, steam, natural gas, air, and other liquids and gases. CSWP, or standard pipe, may also be used in air conditioning systems, in sprinkler systems for fire protection, as structural support for fencing, as piling, as well as for a variety of other mechanical and light load-bearing applications.

[21] The size of CSWP is generally specified by two values: a nominal pipe size (NPS) and a schedule. The NPS relates roughly to the inside diameter of the pipe while the schedule relates to the wall thickness. For a given NPS, the wall thickness will increase as the schedule number increases. For example, CSWP with an NPS of 1 inch (NPS 1) and made to ASTM A53, Schedule 40 requirements will have an outside diameter of 1.315 inches and a wall thickness of 0.133 inch while the same pipe meeting the requirements of ASTM A53, Schedule 80 will have an outside diameter of 1.315 inches and a wall thickness of 0.179 inch.

[22] Although CSWP is generally produced to industry standards such as ASTM A53, ASTM A135, ASTM A252, ASTM A589, ASTM A795, ASTM F1083, Commercial Quality and AWWA C200-97, it may also be produced to foreign standards such as BS1387 or to proprietary specifications as is often the case with fencing pipe. While standard pipe may be manufactured to any of the standards mentioned above, the ASTM A53 specification is the most common as it is considered to be the highest quality and is suitable for welding, coiling, bending and flanging.

[23] Standard pipe may be sold with a lacquer finish, or a black finish as it is sometimes referred to in the industry. It may also be sold in a galvanized finish which means it has been treated with zinc. Both types of finish are intended to inhibit rust although the galvanizing process will deliver a superior result. Galvanized pipe will sell at a premium to black standard pipe because of this, and the fact that zinc costs much more than lacquer.

Classification of imports

[24] The subject goods are normally imported into Canada under the following tariff classification numbers:

- 7306.30.00.42

- 7306.30.00.43

- 7306.30.00.44

- 7306.30.00.45

- 7306.30.00.46

- 7306.30.00.47

- 7306.30.00.49

- 7306.30.00.52

- 7306.30.00.53

- 7306.30.00.54

- 7306.30.00.55

- 7306.30.00.56

- 7306.30.00.57

- 7306.30.00.59

- 7306.30.00.62

- 7306.30.00.63

- 7306.30.00.64

- 7306.30.00.65

- 7306.30.00.66

- 7306.30.00.67

- 7306.30.00.69

[25] Prior to January 1, 2022, the subject goods would have been normally imported into Canada under the following tariff classification numbers:

- 7306.30.00.10

- 7306.30.00.20

- 7306.30.00.30

[26] These tariff classification numbers may also include non-subject goods, and subject goods may also fall under additional tariff classification numbers.

Period of review

[27] The period of review (POR) for the CBSA’s expiry review investigation is January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2023.

Canadian industry

[28] The single largest producer of CSWP in Canada is Nova of Montréal, Québec. Other companies, such as Atlas, Evraz, Welded Tube, and DFI may produce small quantities of CSWP on an irregular basis.

Nova Tube Inc. and Nova Steel Inc.

[29] Nova Tube and Nova Steel are subsidiaries of Novamerican. Nova Tube focuses on pipe and tubular product while Nova Steel specializes in other steel products. Nova has production facilities in both Montréal (Saint-Patrick) and Baie-D’Urfé, Québec. These facilities can produce CSWP in sizes ranging from ½ inch to 7 inches. Nova provides hydrostatic testing, end finishing, cutting, galvanizing, painting, varnishing and distribution services for CSWP.

Canadian market

[30] The apparent Canadian market for CSWP during the POR is indicated by volume and value in Table 1 and by percentage in Table 2 below.

| 20201 | 20211 | 20221 | 2023 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | Value | Volume | Value | Volume | Value | Volume | Value | |

| Canadian productionFootnote 9 | 38,285 | 44,933,076 | 37,129 | 67,426,206 | 42,468 | 87,590,151 | 44,311 | 82,200,218 |

| China | 225 | 355,245 | 34 | 52,328 | 46 | 91,914 | 152 | 191,493 |

| Other countriesFootnote 10 | 79,673 | 119,416,047 | 139,191 | 283,902,726 | 170,890 | 308,415,630 | 92,830 | 222,951,933 |

| Total imports | 79,897 | 119,771,292 | 139,225 | 283,955,054 | 170,935 | 308,507,544 | 92,982 | 223,143,425 |

| Apparent Canadian market | 118,182 | 164,704,368 | 176,354 | 351,381,261 | 213,404 | 396,087,694 | 137,293 | 305,343,643 |

| 1These years do not include DFI’s information due to issues with confidentiality. | ||||||||

| 20201 | 20211 | 20221 | 2023 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | Value | Volume | Value | Volume | Value | Volume | Value | |

| Canadian Production | 32.4% | 27.3% | 21.1% | 19.2% | 19.9% | 22.1% | 32.3% | 26.9% |

| China | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other countries | 65.3% | 70.7% | 76.7% | 78.8% | 76.9% | 74.1% | 67.6% | 73.0% |

| Total imports | 67.6% | 72.7% | 78.9% | 80.8% | 80.1% | 77.9% | 67.7% | 73.1% |

| 1These years do not include DFI’s information due to issues with confidentiality. | ||||||||

[31] Based on information on the administrative record, the total apparent Canadian market increased in volume and value between 2020 and 2022.

[32] The Canadian producers’ share of the apparent market decreased in 2021 and 2022 by both value and volume. However, during 2023, their market share recovered to near 2020 levels.

[33] The market share of CSWP from China remained relatively flat for the entire POR. Imports of CSWP from other countries increased slightly in 2021 and 2022 before dropping back down to 2020 levels.

Enforcement data

[34] In the enforcement of the CITT’s order during the POR, as detailed in Table 3 below, the CBSA assessed a total amount of anti-dumping and countervailing duties of $1.53 million on subject imports from China. The total value for duty of subject imports during the POR from China was approximately $690,979. As a percentage of the total value for duty, the combined anti-dumping and countervailing duties assessed during the POR were equal to 221.4%. The quantity of subject goods, on which anti-dumping and countervailing duties were assessed was roughly 456 MT.

| Country | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 680,215 | 145,600 | 215,093 | 489,246 |

Parties to the proceedings

[35] On February 20, 2024, the CBSA sent a notice concerning the initiation of the expiry review investigation and ERQs to known Canadian producers, importers and exporters. The Government of China (GOC) was also sent an ERQ relating to subsidy.

[36] The ERQs requested information relevant to the CBSA’s consideration of the expiry review factors, as listed in subsection 37.2(1) of the Special Import Measures Regulations (SIMR).

[37] Five Canadian producers, Welded Tube, Evraz, Atlas, DFI, and Nova participated in the expiry review investigation and responded to the ERQs.Footnote 12 One importer, Forest City responded to the CBSA’s ERQ.Footnote 13 No response was received from exporters or the GOC.

[38] Nova and DFI provided case briefs to the CBSA in support of its position that continued or resumed dumping and subsidizing of CSWP from China is likely if the CITT’s order expires.Footnote 14 Atlas submitted a letter of concurrence in support of the continuation of the CITT’s order.Footnote 15

[39] No other party provided a case brief or reply submission.

Information considered by the CBSA

[40] The information considered by the CBSA for purposes of this expiry review investigation is contained in the administrative record. The administrative record includes the information on the CBSA’s exhibit listing, which is comprised of the CBSA exhibits and information submitted by interested parties, including information which the interested parties feel is relevant to the decision as to whether dumping and subsidizing are likely to continue or resume absent the CITT order. This information may consist of expert analysts’ reports, excerpts from trade magazines and newspapers, orders and findings issued by authorities of Canada or of a country other than Canada, documents from international trade organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) and responses to the ERQs submitted by Canadian producers, exporters, importers and governments.

[41] For purposes of an expiry review investigation, the CBSA sets a date after which no new information submitted by interested parties will be placed on the administrative record or considered as part of the CBSA’s investigation. This is referred to as the “closing of the record date” and is set to allow participants time to prepare their case briefs and reply submissions based on the information that is on the administrative record as of the closing of the record date. For this investigation, the administrative record closed on April 10, 2024.

Position of the parties: Dumping

Parties contending that continued or resumed dumping is likely

Nova

[42] Nova made representations through its case brief in support of its position that dumping from China is likely to continue or resume in the event the present order expires. Accordingly, Nova argues that the measures should remain in place.

[43] The main factors identified by Nova can be summarized as follows:

International market conditions

- Global economic conditions

- Global steel market outlook and weak demand

- Global excess capacity

- Global CSWP price volatility

CSWP pricing in the Canadian market

- Pricing of Chinese imports of CSWP in the Canadian market

China’s economic conditions and the CSWP market

- China’s economic conditions

- Steel and CSWP production and overcapacity in China

- China’s steel and CSWP demand

- China’s pipe and HRC prices

- China’s propensity for dumping

- China’s export orientation

International market conditions

[44] Nova submits that international market conditions make it likely that China will export large volumes of CSWP to Canada at low prices over the next 2 years. The international market is volatile and this situation is expected to continue for the next 12 to 24 months.Footnote 16 Global steelmaking capacity continues to grow resulting in both volume and price pressure on steel markets and producers worldwide. Nova argues that the high levels of excess steel capacity, paired with weak economic conditions, falling demand, and declining prices will further incentivize CSWP producers to increase production and to export more goods overseas. Nova further argues that the Red Sea Crisis which disrupted shipping to Europe will lead CSWP producers in China to look to other markets (e.g. Canada) that do not involve shipping through the Red Sea.Footnote 17 These developments are further explained below.

Global economic conditions

[45] Nova cites that the World Bank anticipates economic recovery to be soft following the COVID-19 pandemic, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict, and a rise in global inflation.Footnote 18

[46] Nova notes that the World Bank expects global inflation to remain high beyond 2024. The World Bank projects world GDP growth to remain slow following the initial post-COVID-19 Pandemic recovery. Global GDP growth is forecasted to slow to 2.4% in 2024 and 2.7% in 2025. The World Bank further states that the period from 2020 to 2024 is the weakest start to a decade for global growth since the 1990s.Footnote 19

Global steel market outlook and weak demand

[47] Nova reports that the global steel market was thrown into uncertainty in 2020 caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nova further reports that global inflation and the Russia-Ukraine war have both negatively impacted the steel and CSWP market. Nova points out that Russia and Ukraine are major steel producers and the effects of the war between them will continue to be felt for some time. Supply chain disruptions, lower steel consumption in Russia, lower export prices, and new EU sanctions add to overall instability caused by the pandemic and makes the global steel market even more volatile.Footnote 20 Nova additionally adds that the ongoing Israel-Hamas war may also affect steel supply changes if prolonged.

[48] Nova adds that high inflation and interest rates in 2022 and 2023 have negatively effected steel demand. Nova corroborates this by stating that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have reported that the global market is cooling, while steel production in China has continued to increase.Footnote 21

[49] Nova submits that annual growth projections in the global construction industry are weak at 1.2% in 2024 and are projected to be 2.7% annually on average between 2025 and 2030. Similarly, Nova reports that the tightening of monetary policy globally (i.e. high interest rates) may lead to further contractions in the real-estate and construction sectors.Footnote 22 Nova provided that world residential and non-residential building projects are projected to decline by US$70 billion in 2024.

[50] Nova concludes that the factors discussed above will lead Chinese producers of CSWP to sell more products overseas at increasingly dumped prices.Footnote 23

Global excess capacity

[51] Nova reports that steel capacity expansions are continuing at a constant pace despite the weak outlook for steel demand. Global steelmaking capacity increased by 16.3 million metric tonnes (“MT”) to 2.442 billion MT in 2022 and was expected to increase by an additional 57.1 million MT in 2023 totalling 2.499 billion MT globally.Footnote 24

[52] According to the OECD, the gap between steelmaking capacity and production has been widening. The gap grew from 556.1 million MT in 2022 to 610.8 million MT in 2023.Footnote 25 The OECD further noted that the capacity growth is primarily driven by capacity expansion in the ASEAN region.Footnote 26

[53] Nova argues that the widening capacity-production gap will lead producers with low utilization to increase production volumes in an attempt to spread costs over a larger volume. This increase in production will cause Chinese exporters to sell these excess goods at dumped prices to attractive export markets such as Canada.

Global CSWP price volatility

[54] Nova submits that hot-rolled coil (“HRC”) is a reasonable proxy for CSWP price trends. HRC is the largest raw material component for CSWP and makes up 85% of the total cost of production.Footnote 27 Nova reported that the average price of HRC in the US Midwest, Germany, Italy, UK, India, and China increased in 2021, and dropped in both 2022 and 2023.Footnote 28

[55] Nova argues that in response to declining prices and global instability, CSWP producers in China will likely export CSWP at dumped prices to Canada if the CITT’s order expires because of the relatively higher prices in the North American market.Footnote 29

CSWP pricing in the Canadian market

Pricing of Chinese imports of CSWP in the Canadian market

[56] Nova provided analysis on the CBSA’s Import and Compliance Statistics (re: Exhibits 34 and 35). According to the CBSA’s own statistics, there were only 152 MT of imports from China in 2023. Nova further notes that these imports were priced very low at $1,259/MT, the third lowest (in terms of price per MT) out of all countries.Footnote 30

[57] Nova also notes, that the countries subject to the CSWP2 (Chinese Taipei, India, Oman, South Korea, Thailand, and United Arab Emirates) and CSWP3 (Pakistan, Philippines, Türkiye, and Vietnam) findings were the “low-price leaders” in 2023.Footnote 31 Nova argues that if the CITT’s order expires, producers from China would have to continue to sell CSWP at low prices in order to compete with the prevailing import competition (i.e. CSWP2 and CSWP3 countries).Footnote 32 Nova also included examples of undercutting from countries other than China to further support this claim, and surmised that subject goods from China would have to compete at or below these prices to remain competitive.Footnote 33

China’s economic conditions and the CSWP market

China’s economic conditions

[58] Nova reports that China’s economy is expected to slowdown and enter a potential deflationary crisis. After the COVID-19 lockdowns were lifted, China’s GDP growth in Q1 of 2023 reached 8.9% before subsequently falling to 5.2% for all of 2023. China’s GDP growth is expected to remain low at 4.6% in 2024 and 4.1% in 2025 following low consumer confidence and a struggling real estate market.Footnote 34

[59] Nova states that China’s property sector is ailing, resulting from the country’s two largest developers, Country Garden and Evergrande, defaulting on a significant amount of offshore debt.Footnote 35 Nova additionally cited that the struggling Chinese economy has lead to a significant reduction in both domestic and foreign confidence in China’s economic position. Foreign direct investment in China fell below zero for the first time in decades. At the same time, China’s consumer confidence index also declined by approximately 10%, further showing the fading trust in China’s economy.Footnote 36

Steel and CSWP production and overcapacity in China

[60] Nova submits that in its 94th session, the OECD Steel Committee expressed concern about the growing overcapacity, weakened demand for steel, and the distorting effects of government interventions in the global steel markets. Global steel capacity reached 2.5 billion MT in 2023 and is projected to increase significantly as result of investments in China, the ASEAN countries and surrounding regions.Footnote 37

[61] Nova submits that according to the OECD Steel Committee, the Government of China promotes and supports steel expansion investments through large subsidies, potentially worsening the issues related to the global steel excess capacity and trade distortions.Footnote 38

[62] Nova provided a table summarizing Mysteel’s Steel Pipe Market Review. The table provided by Nova shows significant excess capacity in China’s steel pipe market of 44.4 million MT in 2020, with an estimated increase to 56 million MT in 2024. Furthermore, the table displays a declining utilization rate of all welded pipe manufacturing in China, from 58% in 2020 to an estimated 53% in 2024.Footnote 39 Nova also states there is expected to be an additional 5.74 million MT in new production capacity of welded pipe in the upcoming years.Footnote 40

China’s steel and CSWP demand

[63] Nova indicates that according to the World Steel Association (WSA), steel demand in China for 2024 is uncertain, largely as a result of falling housing sales and new construction sales. In 2024, the WSA anticipates a possible contraction in demand for Chinese steel. The WSA estimated that steel demand would grow by only 2% in 2023 and remain flat (i.e. 0% growth) in 2024.Footnote 41 Nova further cites a report published by the China Metallurgical Industry Planning and Research Institute (MPI), which anticipates a contraction of 1.7% in steel demand, due to slowing construction sector.Footnote 42

[64] Citing a S&P Global Platts report, Nova submits that the weak steel demand in China is due to declining property construction and poor consumption in the real estate sector, both of which are direct downstream industries for steel pipes.Footnote 43 Moreover, Nova provided a table showing how Chinese demand for welded pipe has fluctuated since 2020, with declines in both 2021 and 2023.Footnote 44

China’s pipe and HRC prices

[65] Nova contends that the average prices of Chinese welded pipe experienced a significant drop in 2023, falling by approximately 15%. Nova further asserts that the average price will continue to decline in 2024, by Chinese Yuan of 100-200/MT (roughly US$ 14-28/MT).Footnote 45 Moreover, Nova ascertained that Chinese HRC prices also demonstrated a similar pricing trend – with prices in 2023 reaching it’s lowest level since 2020.Footnote 46 Finally, Nova notes that the difference in price between welded pipe and HRC is small. Nova posits that this is a strong indication that Chinese producers are likely selling CSWP below production costs and would therefore continue to sell to Canada at dumped prices if the order expires.Footnote 47

China’s propensity for dumping

[66] Nova points to the CBSA’s current Measures in Force to display China’s propensity to dump steel products. The CBSA currently has 11 anti-dumping findings in place for steel products (including CSWP) from China.Footnote 48 Nova also provided a list of jurisdictions, other than Canada, that have imposed trade restrictions on CSWP and other steel products from China. Nova states that there are over 300 anti-dumping and countervailing measures on steel products from China.Footnote 49 Additionally, Nova provided a list of “other trade restrictive measures” on CSWP and other steep pipe products, including four Safeguard measures from the European Union and six Section 232 measures from the United States.Footnote 50

[67] Nova argues that the numerous anti-dumping and other restrictive trade measures currently in place against Chinese steel products shows China’s propensity to dump. Nova contends that CSWP exporters would likely continue or resume dumping of subject goods into Canada if the CITT’s order expires.Footnote 51

China’s export orientation

[68] Nova posits that declining steel demand in China paired with production overcapacity will greatly increase the likelihood of continued of resumed dumping of CSWP to Canada, if the CITT’s order expires.Footnote 52

[69] Nova cited a UN Comtrade report, to show that exports of CSWP and other welded steel pipe from China have increased year-over-year since 2020. Chinese exports of CSWP increased 7% Y-o-Y between 2020 and 2021 and further increased 4% between 2021 and 2022.Footnote 53 Nova ascertains that the growth in exports is attributable to low prices in China and weak domestic demand, lead by the contracting real estate and construction sectors.Footnote 54

[70] Nova argues that external factors such as anti-dumping duties, import tariffs, and geopolitical challenges, are all likely to affect the trade flow and export destination of CSWP. Similarly, Nova surmises that the Red Sea shipping issue will divert goods away from the European Union and into other countries. Nova believes that if the CITT’s order expires, these factors will lead to the resumption of dumping of CSWP into Canada.Footnote 55

DFI

[71] DFI made representations through its case brief in support of its position that dumping from China is likely to continue or resume in the event the present order expires. Accordingly, DFI argues that the measures should remain in place.

[72] The main factors identified by DFI can be summarized as follows:

- Commodity nature of subject goods

- Demand in Canadian market

- Chinese exports have continued at dumped and subsidized prices

- Global steel over production and excess capacity

- Weak domestic market in China

- China’s propensity for dumping

- Continued availability of low-priced dumped and subsidized goods

Commodity nature of subject goods

[73] DFI notes that in the CITT’s 2008 Finding (NQ-2008-001), the Tribunal found that “CSWP is a commodity product and that price is usually the principal factor dictating purchasing decisions. In the Tribunal’s opinion, the evidence on the record supports this view.”Footnote 56 DFI also cited the CBSA’s Statement of Reasons (SOR) in the expiry review of CSWP from Chinese Taipei, India, Oman, South Korea, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates, issued on February 2, 2024, in which the CBSA highlighted the interchangeability of imported and domestic CSWP. DFI further references the same SOR, in which the CBSA established that CSWP in Canada has a “high degree of price sensitivity”.Footnote 57

[74] DFI posits that the commodity nature of CSWP leads to price pressures felt by Canadian producers. DFI argues that the prevailing price pressures would result in Canadian producers of CSWP being unable to compete with dumped and/or subsidized CSWP from foreign producers.Footnote 58

[75] DFI points out that in the Reasons for the 2019 CITT’s order in paragraphs 68 to 75, the CITT indicated several reasons that would lead to the “resumption of large volumes of subject goods being diverted to Canada, if the 2019 Order was expired.”Footnote 59 Furthermore, DFI submits that the conditions laid out by the CITT in paragraphs 68 to 75 remain relevant to this expiry review.Footnote 60

Demand in the Canadian market

[76] DFI asserts that demand for CSWP in Canada is less than at the time of the 2019 CITT’s order. DFI also asserts that the removal of dumped CSWP from Pakistan, Philippines, Türkiye, and Vietnam, following the CITT’s finding NQ-2018-003 have improved the prospects of domestic producers. Furthermore, new uses of CSWP have been introduced to the Canadian market, such as solar farm applications.Footnote 61

[77] DFI indicates that demand for CSWP fell during the COVID-19 Pandemic, but has since improved. This is primarily due to the diversification of CSWP usage, such as in solar farms. DFI contends that this increase in demand will pull in imports of dumped and subsidized Chinese exports, similar to piling pipes (like goods).Footnote 62

[78] Additionally, DFI notes that the Canadian carbon pricing (Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, SC 2018, c.12) imposed on Canadian steel producers also impacts price and therefore demand for domestically produced CSWP. DFI notes that there is no border control measures to compensate for the lack of carbon taxation on imported steel from outside of Canada.Footnote 63 DFI posits that producers in China are also “utilizing unfair tax practices to gain a cost advantage.”Footnote 64

[79] DFI argues that if the CITT’s order expires, the absence of carbon taxation on steel imports and the utilization of unfair tax practices, causes subject goods exporters to have an unfair pricing advantage which increases the likelihood of dumped and subsidized goods to enter Canada.Footnote 65

Chinese exports have continued at dumped and subsidized prices

[80] DFI notes that imports from China have been assessed SIMA duties in each year of the POR. DFI argues that this demonstrates China’s continued interest in exporting to Canada. DFI believes that if the CITT’s order expires, the resumption of dumped and subsidized CSWP into Canada is a guarantee.Footnote 66

Global steel over production and excess capacity

[81] DFI cited an OECD report which states, that despite the decline in steel demand and a weak outlook, increases in capacity expansion is expected to continue. The gap between global capacity and crude steel production reached 627.7 million MT in 2022, up from 512.6 million MT in 2021.Footnote 67

[82] In a WSA report cited by DFI, China was the world’s largest steel producer in 2022 at 1018 million MT. The WSA reported that in 2023, China’s steel making capacity was expected to increase to 1173 million MT. DFI further cites a Kallanish Market Report (dated April 5, 2024), in which global steel demand was expected to remain slow in 2024 through to 2025. In the same report, China’s exports of steel was estimated to increase by 40% in 2023.Footnote 68

[83] Furthermore, DFI references a Fastmarkets report, which explained the current “steelmaker’s dilemma” plaguing China. Steelmakers are encouraged to continue producing rather than cut production, as it makes more economical sense to do so.Footnote 69

[84] DFI also referenced an OECD report relating to global steelmaking capacity. The report expects the overcapacity problem to become more serious in the future. OECD further states that capacity growth in excess of demand, will lead to falling steel prices and weak profitability. DFI argues that Canada will become exposed to these falling market prices, if the CITT’s order expires.Footnote 70

[85] In addition, DFI cited the 95th session of the Steel Committee, where the Chair of the OECD Steel Committee stated that “The steel industry is facing unsustainable trends. Excess capacity is enormous and growing. In an environment of limited global steel demand growth, this situation is creating instability in global steel markets and will escalate trade actions.” The Chair also stated that the sudden surge in steel exports from China have the potential to cause more instability and trade actions. DFI contends that if the CITT’s order expires, the current environment will allow for a flood of exports from China.Footnote 71

Weak domestic market in China

[86] DFI points to a Kallanish Report which notes that China’s 2023 trade data shows that there was an increase in net steel exports, as a consequence of both weak domestic demand and the utilization of unfair tax practices. According to this report, steel exports from China increase 38% year-over-year.Footnote 72

[87] DFI submits that Chinese demand for steel accounted for 920.9 million MT of the 1018.0 million MT it produced in 2022. This created a 100 million MT gap between production and demand. DFI also noted that China was expected to add 23.4 million MT of capacity in 2023.Footnote 73

[88] The Kallanish Report indicated that steel demand in China had significantly decreased in 2023. DFI contended that this would lead to even more downward price pressures felt by steel producers. Additionally, the same report notes that the weak domestic demand for steel is lead by a struggling real estate and construction market.Footnote 74

[89] In conclusion, DFI cites a steel outlook report published by the WSA; which expects a slow recovery in steel demand for 2024. The WSA indicated that China’s primary steel using sectors have shown signs of weakening in 2023.Footnote 75

China’s propensity for dumping

[90] DFI argued that weak domestic demand and an increase in Chinese steel exports, show that China has a reliance on exports and a tendency to dump excess production.Footnote 76

[91] DFI points to a Kallanish Commodites March 2024 Market Report which highlights that Vietnam was now China’s top steel export destination. Furthermore, the Kallanish Report concludes that this increase in exports to Vietnam was driven by low prices rather than an increase in demand.Footnote 77

[92] DFI submits that if the CITT’s order expires, Canada will become a target destination for a large volume of subject goods similar to Vietnam. Canadian users of CSWP will seek to purchase pipes at the lowest possible price.Footnote 78

[93] DFI also notes that China’s tendency to export at any price, has lead a large number of nations to restrict exports of CSWP from China. Additionally, DFI points out that there are at least 20 measures in force in nine jurisdictions (other than Canada) on steel pipe products from China.Footnote 79

Continued availability of low-priced dumped and subsidized goods

[94] DFI submitted that it expects the CSWP market in 2024 to remain stable. DFI further submits that the current price compression experienced by Canadian CSWP producers would be exacerbated if the CITT’s order expires.Footnote 80 DFI states that the continued export of subject goods into Canada during the POR illustrates the intention of Chinese exporters to resume dumping and subsidizing.Footnote 81

[95] DFI cites the CITT’s Piling Pipe Reasons (RR-2022-005), in which the CITT determined piling pipe was likely to be available in the Canadian market at low prices in the absence of the order. The CITT also concluded that Chinese pipe producers were willing to undercut domestic pricing during the POR.Footnote 82 In the Piling Pipe Reasons, the Tribunal concluded that the prices of subject goods were likely to undercut the prices of like goods if the order expired.Footnote 83 DFI noted that CSWP is a like good to Piling Pipe, and therefore the Tribunal’s reasoning is directly applicable to this expiry review. Lastly, DFI quoted the CITT’s Reasons, where they found importers of Piling Pipe to be “willfully blind” to the current CITT order. DFI argued that this was an indication of what would happen, given the CITT’s order expires.Footnote 84

[96] DFI pointed to a Kallanish Report in which it discussed the unfair tax practices that Chinese producers were using. It noted that Chinese producers were “double counting VAT receipts on their exports” and passing these discounts onto customers.Footnote 85

[97] Moreover, DFI noted that the SIMA Import and Compliance Statistics for this expiry review show that imports of Chinese CSWP are significantly lower than domestically produced CSWP. DFI further submits that recent price quotes received from Chinese exporters indicate their willingness to offer significantly low prices.Footnote 86

[98] DFI asserts that the 2023 and 2024 Global Affairs Canada (“GAC”) Import Permit Data shows the continued interest of Chinese exporters of CSWP in the Canadian market. The GAC data shows that Chinese prices for “Welded Standard Pipe” are below the prices quoted by DFI.Footnote 87

[99] DFI posits that the CBSA’s Import and Compliance Data and the GAC Import Data indicate a continued presence of Chinese producers in the Canadian market. DFI further asserts that because distribution channels between importers and Chinese producers of CSWP are still in place, if the CITT’s order expired, subject goods would rapidly flood the Canadian market.Footnote 88

Parties contending that continued or resumed dumping is unlikely

[100] None of the parties contended that resumed or continued dumping of subject goods from China is unlikely if the order expires.

Consideration and analysis: Dumping

[101] In making a determination under paragraph 76.03(7)(a) of SIMA whether the expiry of the order is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of dumping of the goods, the CBSA may consider the factors identified in subsection 37.2(1) of the SIMR, as well as any other factors relevant under the circumstances.

[102] Guided by these aforementioned factors, the CBSA conducted its review based on the documentation submitted by the various participants and its own research, all of which can be found on the administrative record. The following list represents a summary of the CBSA’s analysis conducted in this expiry review investigation with respect to dumping:

- Commodity nature of CSWP

- Global steel and welded pipe market conditions

- Economic outlook in China

- Excess production capacity of steel and CSWP in China

- Attractive Canadian market

- Inability of Chinese exporters to sell to Canada at non-dumped prices while the CITT order was in effect

- Imposition of anti-dumping measures by authorities of jurisdictions other than Canada concerning welded pipe from China

- China’s proclivity to dump steel products

Commodity nature of CSWP

[103] Generally speaking, CSWP manufactured either by a Canadian producer or by a foreign producer is physically interchangeable. CSWP manufactured by foreign producers for sale to Canada is generally manufactured to meet Canadian requirements. As noted in the CITT’s original finding “The Tribunal is satisfied that, overall, while not identical in all respects to each other, all types of CSWP have similar physical and market characteristics.”Footnote 89

[104] In the most recent CSWP Expiry Review the CITT stated in its reasons that “CSWP is a commodity product and therefore price is a determinative factor in purchasing decisions.”Footnote 90 Further evidence supporting this point is found within the reasons in the CITT’s original finding where it agreed that CSWP was a commodity product and that price was one of the primary factors in the decision to purchase. Moreover, the Tribunal noted that 15 of the 19 respondents stated that they usually purchased the lowest-priced product.Footnote 91 This confirms the CBSA’s opinion that CSWP is a commodity product and thus, subject to price sensitivity.

[105] As confirmed by the CITT, the CSWP imported from overseas is physically interchangeable with the CSWP produced in Canada. Furthermore, the CITT affirmed that CSWP is a “commodity” and therefore buyers will seek purchase at the lowest price. The CITT’s original finding demonstrated this, by showing that importers were willing to switch to sources where lower prices were available.

[106] Due to the price sensitivity of CSWP and the fact that CSWP produced abroad versus domestic are virtually interchangeable, if the CITT’s order expires there is a likelihood of continued or resumed dumping of subject goods into Canada.

Global steel and welded pipe market conditions

[107] In January 2024, the IMF reported that the global economy was still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian-Ukraine conflict, and an inflationary crisis. Global GDP growth in 2023 was expected to hit 3.1% and remain constant into 2024. The tightening of central bank policy to combat inflation will result in higher mortgage costs and pose challenges to firms refinancing their debt. The IMF notes that increased interest rates will lead to weaker business and residential investment.Footnote 92

[108] Information on the record indicates that high inflation and the subsequent high interest rates have resulted in a decrease in steel demand in 2023. The WSA estimated that steel demand in 2023 would grow by 1.8%, after a contraction of 3.3% in 2022. Steel demand in 2024 would see further growth of 1.9%. Chairman of the Worldsteel Economics Committee commented that the slowing demand for steel is a result of the high interest rate environment, lead primarily by a slowdown in steel using sectors (i.e. construction).Footnote 93

[109] In addition, the precursor of steel demand – the real estate and construction sectors – are also feeling heavy pressure from the inflationary environment. A report published by Oxford Economics, highlights that global construction activity is anticipated to fall 0.3% in 2024 to US$9.6 trillion and rebound 2.4% in 2025 to US$9.8 trillion. The report further states that non-residential building activity is forecasted to fall 0.8% in 2024 to US$2.53 trillion and increase slightly by 0.5% in 2025 to US$2.54 trillion.

[110] Given the information on the record, it is clear that the global economy is still struggling to recover post-COVID-19. Other factors, such as the Russia-Ukraine War and high interest rates are putting strain on supply chains and consequently prices. Tightening global monetary policy, and a downstream slowdown in the construction sector is putting significant pressure on the global steel market. Thus, if the CITT’s order expires, the current volatility in the market represents an opportunity for Chinese exporters to dump excess goods into Canada. As a result, this increases the likelihood of continued or resumed dumping of subject goods into Canada.

Economic outlook in China

[111] The World Banks’s China Economic Update published on December 2023 reports that Real GDP growth for 2022 slowed to 3.0%. China’s economy is expected to pick up in 2023 with Real GDP hitting 5.2%, but overall recovery will remain fragile. The fragility in China’s economy is spearheaded by pressures following the COVID-19 reopening, weakness in China’s real estate sector, high levels of domestic debt, and poor consumer sentiment.Footnote 94

[112] China’s debt has increased significantly, lead by local government financing vehicles (“LGFVs”). LGFVs used for infrastructure development has skyrocketed China’s debt-to-GDP ratio, and as a consequence increased China’s overall debt ratio to levels beyond the average of other high-income countries. Government debt in China hit 50.5% in 2022 and is anticipated to rise in 2023 to 54.9% and 58.3% in 2024.Footnote 95 An S&P Commodity Insights report, stated the central government recently issued a directive to 12 of China’s debt-ridden provinces and municipalities instructing them to halt some state-funded projects starting early 2024. The instructions provided to local governments were to delay or halt construction of projects that had received less than 50% of the planned investment capital. The directive prohibits projects in the transport sector including expressways, airways, and railways. The indebtedness currently plaguing China’s local governments comes from slumping sales seen in the property sector (i.e. new home sales).Footnote 96 The infrastructure and property sectors are a large downstream user of CSWP.

[113] The ongoing debt crisis pressuring the real estate and construction sectors was further worsened by two of the countries largest property giants Evergrande and Country Garden defaulting on US$124.5 billion worth of bonds. This is putting additional pressures on the already struggling financial system in China.Footnote 97 As mentioned above, recent central government policy is halting new spending on infrastructure projects in an attempt to curb the growing debt.Footnote 98

[114] Furthermore, China is experiencing a youth unemployment issue. A release in January 2024 showed a jobless rate of 21.3% amongst youth in China. This suggests a difficult job market and could signal a significant slow down in future growth.Footnote 99

[115] The slow down in China’s economy, ongoing debt issues, and resulting slow down in the construction sector has lead to poor demand for steel in China. Following an S&P Commodity Insights report, “the property and infrastructure sectors combined still account for around 45%-50% of China’s total steel consumption in 2023.” Additionally, China’s steel demand is unlikely to improve in 2024 due to the property sector’s debt issues and local government deleveraging.Footnote 100 A similar report confirms this by noting that new home construction (the biggest steel demand driver in China) is expected to fall into 2024, unless the property sector stabilizes.Footnote 101

[116] Based on the information on the record, it is evident that China’s economy is currently slowing down. As a result of debt-laden local governments and curbed spending – tepid growth in the construction and infrastructure sectors is expected into the near future. Given the weak domestic demand for CSWP, Chinese producers may seek to find opportunities overseas to sell their goods. As such, if the CITT’s order expires there may be an increased likelihood of resumed or continued dumping of CSWP into Canada.

Excess production capacity of steel and CSWP in China

[117] It is evident that excess production capacity in the steel market is reaching an all-time high. In the OECD’s: Latest developments in steelmaking capacity, 2023 edition, it notes that “The ongoing excess capacity crisis is at risk of a significant escalation.” The report mentions that despite declining demand for steel and a weak market outlook, capacity expansions are continuing at a staggering pace. Moreover, it states that these capacity expansions are “often in pursuit of export markets.”Footnote 102

[118] The gap between global production capacity and crude steel production increased from 512.6 million MT in 2021 to 627.7 million MT in 2022 (an increase of 115.1 million MT in absolute terms). Global steelmaking capacity increased by 32.1 million MT in 2022, reaching a total of 2459.1 million MT – the highest global capacity in history.Footnote 103

[119] China and India currently account for 52% of the world’s steelmaking capacity. The same OECD report suggests that due to the China’s large size, even small rates of growth can lead to significant volume changes in steel production.Footnote 104 China will lead the global steelmaking capacity expansion over the next three years. The region is set to increase total steelmaking capacity by 25.0 million MT. By comparison, steelmaking capacity expansion in North America is estimated at 3.0 million MT.Footnote 105

[120] Steel producers in China are presently stuck in a “steelmaker’s dilemma”, according to a Fastmarkets report. Noting the report, “Steelmakers are stuck in a vicious trap where they stand to lose out more if they cut existing production. It makes more economical sense in both the medium and long term for mills to continue production than to scale back their output to recoup their losses.”Footnote 106 Instead of cutting production back, steel producers in China are keeping the mills going in an attempt to spread costs over a larger volume.

[121] The welded steel pipe industry, in particular, is also experiencing overcapacity issues. Welded steel pipe production capacity in China is expected to reach 115 million MT in 2023, with a total production output of 61.7 million MT. This results in a utilization rate of roughly 53%.Footnote 107

[122] CSWP is produced from hot-rolled sheet and strip and the excess capacity affecting the steel industry, including flat-rolled producers, has implications on global markets for CSWP. The CBSA is of the view that, in general, the excess capacity creates readily available feedstock and the wide-ranging trade remedies against hot-rolled sheet in countries around the world restrict market access for exporters of hot-rolled steel.

[123] With steel producers increasing capacity in the pursuit of export markets, it is clear that Canada may be on the radar as a potential market. An ever-increasing gap between steelmaking capacity and production will continue to make the “steelmaker’s dilemma” even more potent. With firms having a large amount of excess capacity, producers of steel will keep production numbers up to reduce fixed costs. This will result in a large amount of excess steel, well above demand, entering the market at very low prices. The CBSA believes that steel producers are encouraged to either convert their steel to CSWP or sell their excess of steel to CSWP producers at low prices. The CBSA also concludes that the “steelmaker’s dilemma” will also directly apply to CSWP producers in China. All of these factors taken in combination may increase the likelihood of continued or resumed dumping of subject goods into Canada, should the CITT’s order expire.

Attractive Canadian market

[124] Real GDP growth in Canada is expected to remain slow at 1.0% in 2024 and recover slightly to 2.0% in 2025. 2023 ended with Canadian Real GDP growth hitting 1.1%.Footnote 108 A report published by the Business Development Bank of Canada (“BDC”), notes that “despite […] high inflation and rising interest rates, the news was generally better than expected for the Canadian economy in 2023”. The report further posits, that inflation is currently having a big impact on company profitability and that Canadian firms are going to have to find strategies to manage rising costs.Footnote 109

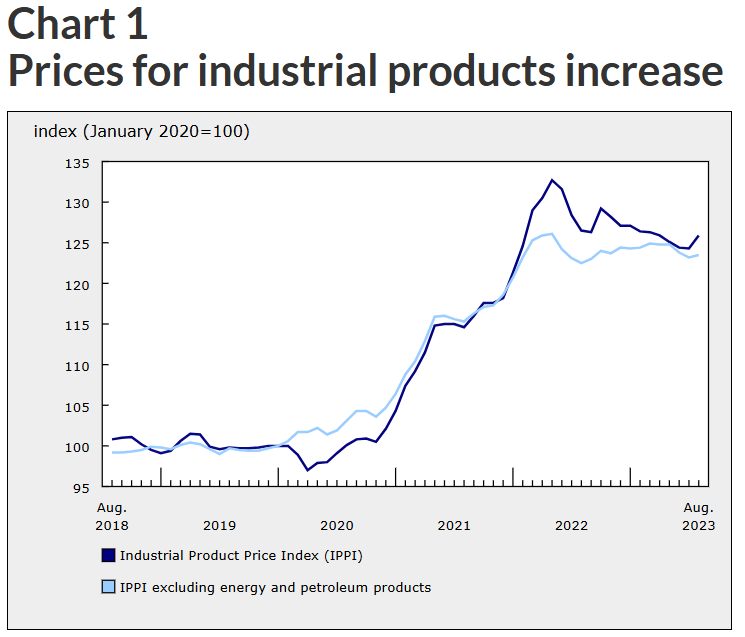

[125] It is known that Canada is currently going through an inflationary crisis. With inflation reaching 6.8% in 2022 before cooling slightly to 4.0% in 2023.Footnote 110 Inflation is expected to remain an issue post-COVID-19, stabling out to 2% in late 2024. Similarly, the industrial product price index (IPPI), which follows the price of products manufactured in Canada (incl. CSWP), also sharply rose during the COVID-19 pandemic. As seen in the chart below, comparing January 2020 (index: 100) to Q1 of 2022 shows an increase of roughly 25% in the price of goods produced in Canada. These high prices have remained high, only dropping slightly in late 2022.Footnote 111

Text description: Chart 1—Prices for industrial products increase

Prices for industrial products increase from August 2018 through August 2023.

Figure 1 - Source: 056 - Stats Can - Industrial Produce and Raw Material Price Index, August 2023

[126] Following high inflation, the Bank of Canada increased key interest rates to 5%. In the Bank of Canada’s – Business Outlook Survey Q4 2023, it reports that growth has been muted particularly in the construction and real estate sectors.Footnote 112 It should be noted that the market for CSWP is closely tied to the performance of the construction sector.Footnote 113 Moreover, firms in these sectors have put projects on hold over 2023 due to high interest rates; high construction costs; and general economic uncertainty.Footnote 114

[127] The Canadian market for CSWP will remain attractive for a few reasons. Growth in Canada’s economy is expected to increase over the near future. Current interest rates have reduced growth in the construction and real estate sectors. Interest rates in Canada are expected to gradually fall as inflation is curbed. The CBSA notes that as interest rates fall, the construction and real estate sectors will begin to recover, largely due to decreased borrowing costs. Consequently, demand for CSWP in Canada will begin to rise. Furthermore, the IPPI is continuing to remain high – with prices being 25% more than they were pre-COVID-19. Due to the commodity nature of CSWP, this increase in price will cause domestic producers to struggle when competing with (potentially) dumped goods from China. As a result of growing demand for CSWP and prevailing high prices of domestically produced goods – Canadian users of CSWP will continue to seek out the cheapest goods possible. Thus, if the CITT’s order expires there is an increased likelihood of the resumption or continuation of dumped subject goods into Canada.

Inability of Chinese exporters to sell to Canada at non-dumped prices while the CITT order was in effect

[128] Imports of subject good from China have declined substantially since anti-dumping duties were first imposed. Low volumes continued to be imported during the POR as seen in Table 1 and Table 2 above. During the POR, imports of CSWP from China accounted for approximately 0.09% in terms of volume and 0.07% in terms of value of the total imports of CSWP.

[129] Based on the Enforcement data section. A total of approximately 456 MT (value of $ 690,979) entered Canada during the POR. Subject imports of CSWP from China were assessed a total of $1.53 million in anti-dumping duties. This is in contrast to the approximately 483,040 MT imports from all sources.

[130] Volume and value has dropped significantly since the last Expiry Review in 2018. Over the previous POR (January 1, 2015 – March 31, 2018), imports totalled 11,194 MT in terms of volume and $15.33 million in terms of value. It is apparent that total imports of CSWP from China had decreased by over 95%.Footnote 115

[131] Imports from China have gone from roughly 1.6% of the total import market to near-zero. This demonstrates that Chinese CSWP exporters have an inability to compete in the Canadian market at non-dumped prices.

[132] In conclusion, if the CITT’s order expires, the apparent inability for Chinese CSWP exporters to compete in the Canadian market at non-dumped prices will be removed. This may lead to the continued or resumed exportation of CSWP at dumped prices into Canada.

Imposition of anti-dumping measures by authorities of jurisdictions other than Canada concerning welded pipe from China

[133] Based on the information on the record, 15 countries, other than Canada have imposed anti-dumping measures on welded pipe and pipe-like products. This information was gathered from the WTO’s Trade Remedies Portal. Countries include, United States, Australia, India and the European Union.Footnote 116

[134] The USDOC published their final decision with respect to circular welded carbon quality steel pipe (CWP) from China on June 22, 2008. This measure has continued to remain in place since then. The USDOC determined dumping margins ranging from 69.20% to 85.55%. In the USDOC’s most recent sunset review, it was found that the revocation of the order on CWP from China would likely lead to the continuation or resumption of dumping.Footnote 117

[135] Looking at Australia’s Anti-dumping Commission, in 2021 the Commission found that “precision pipe and tube steel” from China had been exported into Australia at an amount less than the normal value of the goods (i.e. dumping). Furthermore, the Commission determined dumping margins ranging from 2.9% to 19.7% for goods originating in or exported from China.Footnote 118

[136] Information on the record also indicates that Section 232 measures are in place in the US on standard pipe and tubes and piling pipe from China. Additionally, the European Union has various trade restrictive “safeguards” in place for pipes and other pipe-like products from China. This further limits China’s access to these two essential markets.Footnote 119

[137] The numerous trade measures imposed on welded pipe from China show three things. First, is that China is an export oriented country. When trade measures deny the opportunity to sell into one market, exporters of CSWP in China move onto the next (open) market. Second, is that exporters of CSWP in China have a propensity to dump into any market open to them. Not only are they oriented to sell to new and “open” markets, but they continue to do so at dumped prices. Lastly, given the number of trade measures currently in place globally, exporters of CSWP from China are already limited to what markets they can sell to. Given China’s export orientation, propensity to dump, and market limitation – if the CITT’s order expires, there is an increased likelihood that CSWP from China would continue or resumed to be sold into Canada at dumped prices.

China’s proclivity to dump steel products

[138] Currently, Canada has 11 measures in force against steel products from China. As of the date of this report, Canada has anti-dumping measures in force for the following steel products from China:

- Carbon steel welded pipe

- Steel piling pipe

- Line pipe

- Large line pipe

- Oil country tubular goods

- Seamless casing

- Steel plate

- Corrosion-resistant steel sheet

- Cold-rolled steel

- Reinforcing bar

- Hot-rolled sheet and strip

[139] Based on the fact that the CBSA has current measures in place against like-good to CSWP – piling pipe, feedstock for CSWP – hot-rolled sheet and strip, and multiple other steel products from China, it shows China’s propensity to dump pipe and other steel goods into Canada. As such, the expiry of the CITT’s order would result in an increased likelihood of the continued or resumed dumping of CSWP into Canada.

Determination regarding likelihood of continued or resumed dumping

[140] Based on the information on the record with respect to: commodity nature of CSWP; global steel & welded pipe market conditions; economic outlook in China; excess production capacity of steel and CSWP in China; attractive Canadian market; inability of Chinese exporters to sell to Canada at non-dumped prices while the CITT order was in effect; imposition of anti-dumping measures by authorities of jurisdictions other than Canada concerning welded pipe from China; and China’s proclivity to dump steel products, the CBSA has determined that the expiry of the order is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of dumping of CSWP from China.

Position of the parties: Subsidizing

Parties contending that continued or resumed subsidizing is likely

Nova

[141] Nova made representations through its case brief in support of its position that subsidizing from China is likely to continue or resume should the order expire. Accordingly, Nova argues that the measure should remain in place.

[142] The main factors identified by Nova can be summarized as follows:

- Imposition of countervailing measures on other pipe and tube products from China by Canada

- Imposition of countervailing measures on other pipe and tube products from China by authorities in other countries

- The GOC is very involved in the steel industry

- China’s notification to the WTO

Imposition of countervailing measures on other pipe and tube products from China by Canada

[143] Nova submits that the CBSA has made numerous recent determinations involving pipe and other steel products for goods originating in or exported from China.Footnote 120

[144] In August 2023, the CBSA concluded an expiry review regarding Piling Pipe from China and determined that there was a likelihood of continued or resumed subsidization.Footnote 121 Piling pipe is a type of CSWP and is considered to be a like-good. Nova further submits that CSWP and piling pipe use the same production process, which also suggests that CSWP producers are receiving the same countervailable subsidies.Footnote 122

[145] Nova contends that the CBSA also determined the likelihood of resumed or continued subsidization with regards to four other pipe products from China – seamless casing, large line pipe, line pipe, and oil country tubular goods.Footnote 123

[146] Lastly, Nova submits that Canada has other steel products from China that are subject to countervailing duties. These products include cold-rolled steel, rebar, corrosion-resistant steel sheet, sucker rods, and wind towers. Nova argues that this further indicates that there is a likelihood of resumed or continued subsidization from China if the Order expires.Footnote 124

Imposition of countervailing measures on other pipe and tube products from China by authorities in other countries

[147] Nova contends that many countries, other than Canada, have imposed countervailing measures on pipe, tube, and other steel products from China.Footnote 125

[148] Nova cited the USDOC’s 2019 Second Sunset Review concerning “Circular Welded Carbon Quality Steel Pipe” from China. The USDOC concluded that the revocation of the order would likely lead to a continuation or recurrence of countervailable subsidy ranging between 39.01% and 620.08%.Footnote 126

[149] Moreover, Nova cited the Australian Anti-dumping Commission’s “Hollow structural sections” (HSS) inquiry from 2019. The Commission found net countervailable subsidy rates on HSS from China ranging from 3.3% to 51.0%. Australian authorities have also identified a total of 60 countervailable subsidies programs applicable to exporters of HSS from China.Footnote 127

[150] Nova concludes that the existence of multiple countervailing measures imposed by countries other than Canada, indicates that the GOC is continuing to provide countervailable subsidies to CSWP exporters.Footnote 128

The GOC is very involved in the steel industry

[151] Nova asserts that the GOC has been very involved in the domestic steel industry for a considerable period of time. The GOC has implemented a production capacity replacement policy, an environment protection transformation policy and a technological innovation policy, all of which directly affect the steel industry. All three policies provide subsidies or government programs to producers of steel in China.Footnote 129

[152] Nova also asserts that local governments also provide significant subsidies to the domestic steel industry. Nova notes that certain provinces provide preferential “land use, electricity, and water” rates to assist in reducing operating costs.Footnote 130

[153] Nova posits that national and regional authorities have been promoting new controls in the recent years, such as the “Five-Year Plans for the Development of the Steel Industry.” Nova notes that these measures have been implemented to “stabilise international market share and to expand domestic demand and consumption of steel”.Footnote 131

[154] Nova provided evidence of the “Steel Industry Stable Growth Work Plan”, released in 2023 by a joint effort of seven governmental departments. The plan aims to smooth steel industry operations and accelerate high-quality development. Steel mills are encouraged to install electric furnaces and will be able to receive loan subsidies to do so.Footnote 132

[155] Similarly, the GOC’s “14th Five-Year Plan” has arranged for RMB3.8 trillion in local government special bonds to help encourage more private capital to assist in the construction of major national projects. Provinces have also followed suit, promising subsidies to companies to help with “investing in industrialisation and technological transformation projects.”Footnote 133

[156] Nova argues that the GOC, on both a nation and regional level, is a key supporter of the domestic steel industry. Providing financial and legislative support to the domestic steel industry is likely to also benefit CSWP producers by providing similar benefits.Footnote 134

China’s notification to the WTO

[157] Nova submits that according to China’s most recent notification to the WTO regarding subsidy programs, there are potentially 152 countervailable subsidy programs available to producers and exporters of CSWP.Footnote 135

DFI

[158] DFI made representations through its case brief in support of its position that subsidizing from China is likely to continue or resume should the order expire. Accordingly, DFI argues that the measures should remain in place. The representations DFI made with respect to subsidy were identical to the arguments summarized above in the paragraphs 71 through 99.

Parties contending that continued or resumed subsidizing is unlikely

[159] None of the parties contended that resumed or continued subsidizing of subject goods from China is unlikely if the order expires.

Consideration and analysis: Subsidizing

[160] In making a determination under paragraph 76.03(7)(a) of SIMA as to whether the expiry of the order is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of subsidizing of the goods, the CBSA may consider the factors identified in subsection 37.2(1) of the SIMR, as well as any other factors relevant under the circumstances.

[161] Guided by these aforementioned factors, the CBSA conducted its review based on the documentation submitted by the various participants and its own research, all of which can be found on the administrative record. The following list represents a summary of the CBSA’s analysis conducted in this expiry review investigation with respect to expiry:

- Imposition of countervailing measures on other pipe, tube and steel products from China by Canada

- Imposition of countervailing measures concerning CSWP from jurisdictions other than Canada

- Continued availability of subsidy programs for CSWP producers/exporters in China

Imposition of countervailing measures on other pipe, tube and steel products from China by Canada

[162] Currently, Canada has eight countervailing measures in force against steel products from China. As of the date of this report, Canada has countervailing measures in force for the following steel products originating in or exported from China:

- Carbon steel welded pipe

- Steel piling pipe

- Line pipe

- Large line pipe

- Oil country tubular goods

- Seamless casing

- Cold-rolled steel

- Reinforcing bar

[163] Based on the fact that the CBSA has current measures in place against piling pipe (like-goods to CSWP) and multiple other steel products from China – shows that the GOC continues to subsidize it’s steel industry. As such, it is likely that exporters from China will benefit from continued or resumed subsidizing if the order expires.

Imposition of countervailing measures concerning CSWP from jurisdictions other than Canada

[164] Based on the information on the record, three countries, other than Canada have imposed countervailing measures on welded pipe and pipe-like products. This information was gathered from the WTO’s Trade Remedies Portal. Countries include, United States, Australia, and India.Footnote 136

[165] The USDOC published their final decision with respect to “circular welded carbon quality steel pipe” (CWP) from China on June 5, 2008. This measure has continued to remain in place since then. The USDOC determined ad valorem countervailable subsidy rates ranging from 29.62% to 616.83%. In the original investigation, the USDOC found 23 countervailable subsidies that were provided to CWP producers in China. In the USDOC’s most recent sunset review, it found that the revocation of the order on CWP from China would likely lead to the continuation or recurrence of countervailable subsidization.Footnote 137

[166] Looking at Australia’s Anti-dumping Commission, in 2021 the Commission found that “precision pipe and tube steel” from China had received countervailable subsidies. Furthermore, the Commission determined a subsidy margins ranging of 42.7% for goods originating in or exported from China.Footnote 138

[167] The numerous countervailing measures imposed on welded pipe from China shows that the GOC has a continued interest in the domestic pipe, tube, and steel market. Government agencies in China are continuing to provide countervailable subsidies to pipe and tube producers in China. These same pipe and tube producers have the ability to easily export into Canada. Thus, if the CITT’s order expires, there is an increased likelihood that subject goods from China will resume or continue to be subsidized.

Continued availability of subsidy programs for CSWP producers/exporters in China

[168] The results of the CBSA’s 2008 subsidy investigation of CSWP from China represents the best information available with respect to which subsidy programs continue to be available to CSWP exporters in China. In the CBSA’s most recent re-investigation, which concluded in 2011, there was no cooperation from the GOC or any exporters of CSWP. Consequently, the CBSA is continuing to use the ministerial specification subsidy rate of 5,280 RMB per MT, which was determined in the 2008 investigation.Footnote 139

[169] Moreover, China’s most recent notification to the WTO regarding its subsidy programs, shows that there are potentially 152 countervailable subsidies available to producers and exporters of CSWP.Footnote 140

[170] In the present expiry review investigation, neither the GOC nor exporters in China provided any information regarding updates to subsidy programs available to CSWP exporters in China. Based on this fact and the other information on the record, if the CITT’s order expires, there is an increased likelihood that subject goods from China will resume or continue to be subsidized.

Determination regarding likelihood of continued or resumed subsidizing

[171] Based on the information on the record with respect to: imposition of countervailing measures on other pipe, tube and steel products from china by Canada, imposition of countervailing measures concerning CSWP from jurisdictions other than Canada and continued availability of subsidy programs for CSWP producers/exporters in China, the CBSA has determined that the expiry of the order is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of subsidization of CSWP from China.

Conclusion

[172] For the purpose of making a determination in this expiry review investigation, the CBSA conducted its analysis within the scope of the factors found under subsection 37.2(1) of the SIMR and considered any other factors relevant in the circumstances. Based on the foregoing analysis of pertinent factors and consideration of information on the record, on July 18, 2024, the CBSA made a determination pursuant to paragraph 76.03(7)(a) of SIMA that the expiry of the order made by the CITT on March 28, 2019, in Expiry Review No. RR-2018-001 in respect of CSWP originating in or exported from China:

- is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of dumping of the goods from China and

- in is likely to result in the continuation or resumption of subsidizing of the goods from China

Future action

[173] The CITT has now initiated its expiry review to determine whether the continued or resumed dumping and subsidizing are likely to result in injury. The CITT’s expiry review schedule indicates that it will make its decision by December 24, 2024.

[174] If the CITT determines that the expiry of the order with respect to the goods is likely to result in injury, the order will be continued in respect of those goods, with or without amendment. If this is the case, the CBSA will continue to levy anti-dumping and/or countervailing duties on dumped and/or subsidized importations of the subject goods.

[175] If the CITT determines that the expiry of the order with respect to the goods is not likely to result in injury, the order will expire in respect of those goods. Anti-dumping and/or countervailing duties would then no longer be levied on importations of the subject goods, and any anti-dumping and/or countervailing duties paid in respect of goods that were released after the date that the order was scheduled to expire will be returned to the importer.

Contact us

[176] For further information, please contact the officer listed below:

- Telephone:

- Alexander Ferracuti: 343-553-1890

Doug Band

Director General

Trade and Anti-dumping Programs Directorate

Page details

- Date modified: