Integrated Cargo Security Strategy

Integrated Cargo Security Strategy Pilots Assessment

This report is a summative assessment of the Integrated Cargo Security Strategy (ICSS), which was developed by Canada and the United States (US) as part of the Beyond the Border Action Plan.

Introduction

On December 7, 2011, Prime Minister Stephen Harper and President Barack Obama released the Beyond the Border Action Plan, which outlined a mutual vision to strengthen the security of the Canada-United States (US) perimeter and promote economic competitiveness. The Action Plan established a new long-term partnership between Canada and the US, aimed at facilitating the legitimate flow of people and goods between both countries while strengthening security and promoting economic competitiveness.

As part of the Action Plan, Canada and the US agreed to develop a harmonized approach to screening inbound cargo arriving from offshore, with the expectation that this would result in increased security and the expedited movement of secure cargo across the Canada-US border. In support of this commitment, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Transport Canada (TC) jointly developed the Integrated Cargo Security Strategy (ICSS) to address risks associated with shipments arriving from offshore based on informed risk management. A series of pilots were subsequently launched to test, validate and shape the implementation of the ICSS, namely:

- The Prince Rupert pilot;

- The Montreal pilot;

- The Tamper Evident Technology pilot; and

- The Pre-load Air Cargo Targeting (PACT) pilot.

In addition, Canada and the US agreed to undertake a study to assess the feasibility of conducting Wood Packaging Material (WPM) inspections at the First Point of Arrival (FPOA), utilizing a harmonized perimeter approach.

The following report summarizes and analyzes the results of the ICSS pilots. This report specifically focuses on the Prince Rupert, Montreal and Tamper Evident Technology pilots. The assessment of the PACT pilot has been identified as a Canadian undertaking and is being led by the CBSA and TC.

Integrated Cargo Security Strategy

The ICSS was jointly developed by the CBSA, TC and CBP to identify and resolve security and contraband concerns as early as possible in the supply chain or at the perimeter, with the expectation that this would reduce the duplication of efforts and processes at the Canada-US land border. The ICSS promotes two strategic objectives:

- Identifying and mitigating risks early; and

- Facilitating the flow of legitimate cargo.

To fulfill these strategic objectives, Canada and the US committed to developing and initiating a series of pilots that were expected to test, validate and shape the implementation of the ICSS. Each pilot was intended to run for a period of approximately 18 months, including a six-month assessment period. Based on the results of the pilots’ assessment, recommendations for next steps would be formulated. The pilots’ success would ultimately be measured by achieving a clear reduction in the number of shipments subjected to re-inspection at the Canada-US border on an annual basis, using 2011 as a baseline year.

Integrated Cargo Security Strategy Pilots

Under the ICSS, Canada and the US agreed to launch the following pilots:

- The Prince Rupert pilot;

- The Montreal pilot;

- The Tamper Evident Technology pilot;

- The Newark pilot; and

- The In-transit/In-bond pilot.

Prince Rupert pilot

Launched on October 1, 2012, in collaboration with the Canadian National Railway (CN), the Prince Rupert pilot was designed to facilitate the flow of cargo arriving at the Port of Prince Rupert and transiting to the US by rail. Under the pilot, CBP targeted US-bound cargo for security concerns before arrival at the Port of Prince Rupert, allowing the CBSA to conduct examinations at the perimeter before the cargo moved by rail to the US at International Falls, Minnesota.

Montreal Pilot

Launched on January 7, 2013, the Montreal pilot was designed to facilitate the flow of cargo arriving at the Port of Montreal and transiting to the US by highway. Under the pilot, CBP targeted US-bound cargo for security concerns before arrival at the Port of Montreal, allowing the CBSA to conduct examinations at the perimeter before the cargo moved by truck to various US land border crossings.

Tamper Evident Technology Pilot

The Tamper Evident Technology pilot was launched on October 1, 2012 in Prince Rupert and on January 7, 2013 in Montreal. The pilot was designed to assess the integrity of tamper evident technology by securing cargo transiting through Canada and destined to the US. Under the pilot, containers examined and released by the CBSA in Prince Rupert and Montreal were secured with high security bolt seals, thereby ensuring the contents were not subjected to unauthorized access while traveling to the US.

Newark Pilot

Led by CBP, the Newark pilot was intended to facilitate the flow of cargo arriving at the Port of Newark and transiting to Canada by highway. The pilot was projected to be launched in conjunction with the Prince Rupert and Montreal pilots, allowing Canada to test and validate the ICSS from a northbound perspective.

In-transit/In-bond Pilot

Led by CBP, the in-transit/in-bond pilot was designed to test a new module for the processing of in-transit and in-bond cargo travelling by truck.

Additional Action Plan Commitments

Wood Packaging Material Feasibility Study

Under the Action Plan, Canada and the US agreed to conduct a study to assess the feasibility of conducting WPM inspections at the FPOA, using a harmonized perimeter approach. A working group was subsequently created with representatives from the CBSA, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), CBP and the US Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). The group was tasked with comparing Canadian and US legislation and operational realities to determine whether a harmonized perimeter approach to the collaborative inspection of WPM at the FPOA would be feasible.

The working group determined that sharing of WPM inspection information aimed at identifying high-risk shipments is a realistic approach to facilitating cooperation between Canada and the US’ enforcement of the International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures 15 (ISPM 15) requirements under the Beyond the Border Action Plan.

The working group also concluded, after a thorough review of each country’s respective systems, that there is still essential work needed to ensure parity between the US and Canadian WPM inspection regimes and prepare for implementation of a WPM information sharing inspection approach in the marine mode. As these efforts progress, the US and Canadian teams should consult with their respective stakeholders on the way forward.

A formal exchange of letters between the CBSA, CFIA, APHIS, and CBP outlines commitments to align, or work towards aligning, certain WPM policies, and to consult with stakeholders prior to initiating WPM inspections at the perimeter.

Lessons Learned

Canada and the US have strived to fulfill the strategic objectives of the ICSS through the pilots. The ICSS pilots have generated notable successes; however, they have also faced challenges which have enabled both countries to draw valuable lessons.

1. Information Sharing

Under the ICSS, the CBSA and CBP utilized a system, which allowed both agencies to share information for security concerns, including examination results and images, as well as mitigate risks for containers arriving at the ports of Prince Rupert or Montreal and transiting to a US land border.

Although this tool was deemed successful it was exceptionally used for the ICSS pilots. Both the CBSA and CBP recognize that there are information sharing limitations and agreed that going forward a system which would allow for additional functionality may be required.

2. Risk Mitigation and Trade Facilitation

As outlined in the Action Plan, the ICSS was designed to mitigate risks early and facilitate the flow of legitimate cargo between Canada and the US. The ICSS pilots were specifically intended to address national security and contraband concerns; however, the Prince Rupert pilot also elevated awareness of a high level of agricultural risks which equally pose a potential threat to Canada and the US.

a) National security

Through the Prince Rupert pilot, Canada and the US succeeded in testing the concept of mitigating risks at the perimeter for national security purposes. In fact, the pilot demonstrated that in-transit containers presenting national security concerns could be targeted, examined and risk-mitigated at the perimeter. Nonetheless, in the absence of the Newark pilot, this concept has not been tested from a northbound perspective.

Under the Prince Rupert and Montreal pilots, the CBSA and CBP worked together to risk assess and mitigate national security risks at the earliest point possible.

Figure 1 – Statistics as of January 31, 2015

| Prince Rupert Pilot | Montreal Pilot | |

|---|---|---|

| Containers targeted by CBP for national security | 115 | 50 |

| Containers examined by the CBSA for national security | 51 | 16 |

| Containers re-examined by CBP for national security | 0 | 0 |

| Containers re-examined by CBP for other reasons | 2 | 2 (out of scope*) |

| *2 containers were re-examined by CBP under the Montreal pilot, but were out of scope as they left the Port of Montreal by rail | ||

As indicated in Figure 1, under the pilots, no containers examined by the CBSA for national security purposes were subsequently re-examined by CBP for the same concerns. A marginal number of containers were re-examined upon arrival in the US, but for reasons that could not have been mitigated under the pilots (e.g., agricultural concerns).

b) Contraband

As part of the ICSS, Canada and the US agreed to work together to identify and resolve contraband concerns as early as possible in the supply chain or at the perimeter. Although national security risks were successfully mitigated at the perimeter, unanticipated circumstances hindered both countries’ ability to mitigate contraband concerns under the ICSS.

Due to differences between the Canadian and American targeting models, including differences in legislative authorities (e.g., both countries do not regulate the same commodities), as well as different operational processes (e.g., where examinations occur within the supply chain), the CBSA and CBP have been unable to jointly address contraband concerns under the ICSS pilots.

Should the mitigation of contraband concerns be pursued in the future, both countries recognize that changes, including possible legislative and regulatory changes, may be required to reconcile existing differences and establish common grounds for contraband targeting.

c) Wood packaging material and agricultural risks

Although the ICSS pilots were initially intended to address national security and contraband concerns, greater awareness of agricultural risks emerged as a consequence of the Prince Rupert pilot. Since the launch of the pilot, CBP has enhanced its targeting efficiencies to identify pest risks associated with cargo entering North America through Prince Rupert. This has resulted in an increase in emergency action notifications for non-compliant shipments, the majority of which are due to contaminants (i.e., soil, seeds, snails, hitchhiking pests and noxious weeds).

The CBSA and CBP recognize the impact of agricultural risks and are committed to supporting the CFIA and APHIS to address agricultural examinations outside the confines of the Prince Rupert pilot.

3. Technology

As outlined in the ICSS, Canada and the US agreed to work together to improve verification and detection capabilities through technology. This would ultimately result in the interdiction of illicit cargo through the use of innovative technology and countermeasures. This concept has been tested through the Tamper Evident Technology pilot and helped validate the effectiveness of tamper evident seals.

Under the Tamper Evident Technology pilot, the CBSA was able to test tamper evident seals, thereby ensuring the integrity of containers transiting through Canada to the US. The pilot allowed the CBSA to achieve a better understanding of different types of tamper evident technology and their capabilities. In addition, the pilot demonstrated that the use of tamper evident technology provides an added layer of security which helps safeguard the integrity of these containers. Nevertheless, existing measures (e.g., Large Scale Imaging (LSI) and de-stuff examinations) have proven to be sufficient to identify risk mitigated containers. Both Canada and the US agree that the use of tamper evident technology served to provide an additional layer of security.

4. Cost and Time Savings

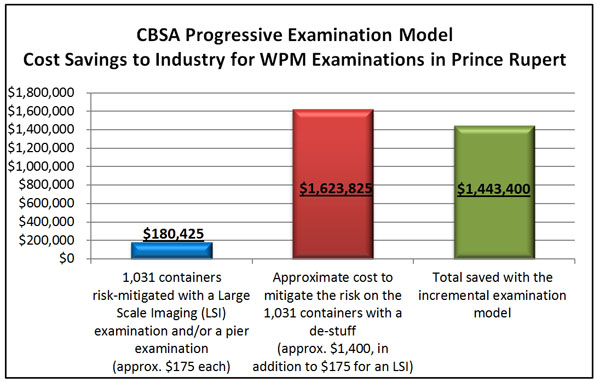

Under the Prince Rupert and Montreal pilots, the CBSA tested a progressive examination model for containers transiting through Canada and destined to the US, similar to the three-tiered process used by CBP. This model allows for an examination to gradually progress, as warranted, from the least intrusive measure (i.e., an LSI examination) to the most intrusive measure (i.e., a de-stuff examination). The progressive examination model has resulted in cost savings for industry, notably for containers examined by the CBSA.

Figure 2 – Statistics as of January 31, 2015

As illustrated in Figure 2, the CBSA’s use of the progressive examination model for containers examined in Prince Rupert has resulted in significant cost savings for industry. Likewise, this model has been successful in Montreal and could potentially be implemented throughout Canada. The cost savings illustrated within Figure 2 do not reflect costs associated with examinations conducted by CBP.

In addition to generating cost savings, the Prince Rupert pilot has resulted in time savings for industry. In fact, the pilot has led to a decrease in train dwell times at the Canada - US land border. Prior to the launch of the pilot, CN reported an average train dwell time of approximately two hours. Following the pilot’s launch, CN started designating specific trains, known as pilot trains, which exclusively transported containers that were risk assessed and examined by the CBSA on behalf of CBP prior to arrival at the US land border. Since the pilot’s launch, the dwell times of pilot trains have been reduced to an average of 22 minutes, thus facilitating the flow of legitimate cargo. In spite of the decrease in the average dwell time of pilot trains, as of September 2013, CN stopped designating pilot trains as the process was not operationally feasible for CN.

Pilot Results

Prince Rupert Pilot

Through the Prince Rupert pilot, Canada and the US have been able to test the strategic objectives of the ICSS and identify best practices.

A distinguishing characteristic of the pilot is its location which, from the onset, was determined to be ideal. Unlike other locations, which often include multiple rail lines and various land border crossings, Prince Rupert consists of one dedicated rail line to one land border crossing. As such, Canada and the US agreed that it would be an optimal location to track and facilitate the accelerated movement of secure containers transiting through Canada and destined to the US at International Falls, Minnesota.

The pilot has yielded successful results that can be leveraged:

- Under the pilot, the CBSA and CBP have successfully been able to jointly risk assess in-transit containers for national security concerns. As noted above, during the course of the pilot, no in-transit containers examined by the CBSA at the perimeter were subsequently re-examined by CBP for national security upon arrival at the US land border.

- The CBSA and CBP have been able to share information, including examination results and images, through an information sharing system.

- Prior to the launch of the pilot, CN made system changes which provided CBP with the ability to link a marine manifest to a rail manifest prior to a vessel’s arrival at the FPOA. During the pilot, CBP was able to target for agriculture risks and maintain examination rates below 0.50% although the total number of shipments increased exponentially.

- Under the pilot, the CBSA tested a progressive examination model for in-transit containers which has resulted in cost savings and time savings for industry.

In spite of the above-noted successes, the following challenges emerged throughout the pilot’s life cycle:

- Due to differences between the Canadian and American targeting models, including differences in legislative authorities (e.g., both countries do not regulate the same commodities), as well as different operational processes (e.g., where examinations occur within the supply chain), the CBSA and CBP have been unable to address contraband concerns under the pilot.

- The pilot elevated awareness of the high level of agricultural risk in cargo entering North America through Prince Rupert. However, CBP’s agricultural examination rate has remained under 0.50%, while the non-compliance rate (targeting efficiency rate) has increased from 2.5% to 45.9%. Most of the agricultural examinations have been tailgates as opposed to more intrusive full container examinations.

Given the challenges that emerged under the Prince Rupert pilot, including the number of shipments found non-compliant for agricultural concerns, Canada and the US recognize that additional work is required to fully achieve the strategic objectives of the ICSS.

Montreal Pilot

Like the Prince Rupert pilot, the Montreal pilot has generated positive results that can be leveraged:

- Under the pilot, the CBSA and CBP have been able to share information through a system.

- The CBSA also tested a progressive examination model for containers arriving at the Port of Montreal transiting to the US which has resulted in cost savings and time savings for industry.

While there have been some achievements under the pilot, various challenges have hindered its overall success:

- The CBSA and CBP have been unable to address contraband concerns under the Montreal pilot due to differences between the Canadian and American targeting models, including differences in legislative authorities and operational processes.

- Canada and the US do not have system capabilities to track the movement of multi-modal shipments from a marine port to a land border crossing. Currently, there are no linkages between the marine and highway data transmitted by carriers. Although multi-modal tracking constituted a technical challenge during the course of the Montreal pilot, it did not impact the CBSA and CBP’s ability to target in-transit containers and/or conduct examinations.

- None of the containers targeted by CBP as part of the Montreal pilot have been identified as having crossed the US by truck. All targeted containers departed by rail and were consequently outside the scope of the pilot.

Overall, the Montreal pilot has faced substantial challenges which have hampered its ability to meet the commitments of the Action Plan.

Tamper Evident Technology Pilot

The pilot has demonstrated that the use of tamper evident technology is an effective means of securing cargo. Moreover, the pilot validated the security of the Asia – Pacific rail corridor for containers examined after arrival in Canada. In fact, since the launch of the pilot, no seals were identified as being broken or tampered with upon arrival into the US.

A secondary component of the Tamper Evident Technology pilot was to test reusable electronic seals. To fulfil this objective, the CBSA tested electronic seals within Canada at the ports of Prince Rupert and Montreal, and subsequently in Vancouver. Electronic seals were utilized to secure containers from the marine terminals to the marine container examination facilities, allowing the CBSA to test their effectiveness domestically.

Although Canada and the US were unable to test electronic seals bi-nationally, both Canada and the US agree that the use of tamper evident technology served to identify risk mitigated containers and provided an additional layer of security.

Newark Pilot & In-Transit / In-Bond Pilot

Due to extenuating circumstances, including US budgetary constraints, both the Newark and In-transit / In-bond pilots could not be launched.

Stakeholder Engagement

Stakeholders from various facets of the Canadian and American trade industry have played an integral role in the development and execution of the ICSS. The CBSA, CBP and TC have been in regular consultations with stakeholders and ensured their views and perspectives were considered throughout the evolution of the ICSS.

Partners and Stakeholders

- Border Agencies

- Transportation Agencies

- International Maritime Organization

- Industry & Supply Chain Stakeholders

Throughout the course of the ICSS, stakeholders, including members of the Canadian Border Commercial Consultative Committee and the US Advisory Committee on Commercial Operations were apprised of the ICSS pilots.

In general, stakeholders are supportive of the pilots and acknowledge the benefits of the progressive examination model. In the case of the Montreal pilot, some stakeholders are of the view that the pilot could have been more fruitful if the scope was changed to marine-to-rail. Nonetheless, they are cognizant that through the pilot, Canada and the US have been able to share information for in-transit containers that arrived at the Port of Montreal.

As a key stakeholder for the Prince Rupert pilot, CN has been actively involved. CN invested in system changes prior to the launch of the pilot to allow the linkage of marine and rail manifests. CN, the Canada and US Customs agencies believe that the pilot’s expressed objective of increasing the focus on North American security to the perimeter, and thereby reducing national security inspections at the Canada-US border, was achieved.

Agriculture examinations were not within the scope of the Prince Rupert pilot. The linkage of the marine and rail manifests originally intended to facilitate security screening at the North American perimeter also provided an opportunity for enhanced agricultural screening. Due to a variety of factors, including an increased volume of rail shipments and higher incidence of shipments found to be non-compliant for agricultural concerns due to improved CBP targeting capabilities, CN has reported an increase in cargo delays and additional trade chain costs for shipments at this border crossing point. CN has taken action to mitigate these concerns at International Falls, but CN notes that its competitors are not subject to a comparable level of inspections at other border ports of entry. CBP maintains, however, that the Prince Rupert pilot has placed CN at a competitive advantage as the advance data often helps mitigate agricultural issues (such as document review) in advance, thus reducing the need to put containers on hold for agricultural purposes.

Subsequent to the commencement of the pilot, CN invested in a fumigation facility at International Falls to allow for the treatment of certain agricultural risks to address logistical challenges presented by infested shipments. The new facility is anticipated to reduce significantly the number of refused containers that are returned through Canada for offshore export, as well as to facilitate the return of any such containers that are transported through Canada. Additionally, CBP recently developed a Carrier Conveyance Contaminants Trade Outreach document, which has been shared with partners and stakeholders, including the CBSA and CN. This new document is part of a series of trade outreach material that currently includes WPM intended to educate trade stakeholders about agriculture risk.

All participants agree that valuable lessons have been learned with respect to security exams and agricultural risks in the nearly 29 months that the Prince Rupert pilot has been undertaken. The greater time period provided to Customs agencies to review cargo data by linking the marine and rail manifests facilitates these agencies’ targeting processes, thereby strengthening national security as well as reducing the risk of potential infestation from harmful pests. As the formal pilot comes to a conclusion, all parties seek to apply these lessons expeditiously on a broader scale for cross-border cargo transported by all carriers at all Canada-US border ports of entry.

Another stakeholder, Maher Terminals, were very receptive of the Prince Rupert pilot and were pleased to learn that 100% of the security-related issues that emerged during the course of the pilot had been mitigated at or prior to arrival at the perimeter. In addition, they were pleased to know that none of the risk assessed containers examined in Canada were re-examined in the US and that no pilot seals had been tampered with while transiting to the US.

Likewise, the Prince Rupert Port Authority (PRPA) was satisfied with the positive exposure that Prince Rupert received as a result of the pilot. Representatives from the PRPA admitted that they had a minimal role in the pilot, but noted that they were pleased with the progress made under the pilot.

Conclusion

The ICSS was developed in view of mitigating risks early and facilitating the flow of legitimate cargo between Canada and the US. The ICSS pilots have led to several successes; however, various challenges have also been encountered. Both countries agree that additional work is required to address the challenges that arose under the pilots, make necessary amendments and potentially fully implement the ICSS.

Considerations for Next Steps

Based on successes and lessons learned from the ICSS pilots, the following are considerations for next steps which may enable both countries to fully achieve the intended efficiencies at the Canada–US land border:

- Canada and the US formally conclude the Prince Rupert pilot and work together to implement the mitigation of national security risks at the perimeter under existing Canada – US agreements;

- Formally conclude the Montreal pilot;

- Support the CFIA and APHIS in implementing the WPM Feasibility Study recommendations;

- Continue to work together to identify an information sharing system which will include additional functionalities;

- Implement the Canadian progressive examination model as a standard national CBSA practice, thereby harmonizing the CBSA’s examination processes with those of CBP; and

- Explore bi-national options to mitigate contraband concerns (i.e., narcotics) at the perimeter.

- Date modified: