Common menu bar links

ARCHIVED - Anti-dumping and Countervailing Program

This page has been archived.

This page has been archived.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

OTTAWA, March 03, 2009

4214-22 AD/1379

4218-26 CV/124

STATEMENT OF REASONS

Concerning the making of final determinations with respect to the dumping and subsidizing of

CERTAIN ALUMINUM EXTRUSIONS ORIGINATING IN OR EXPORTED FROM THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

DECISION

On February 16,2009, pursuant to paragraph 41(1)(a) ofthe Special Import Measures Act, the President of the Canada Border Services Agency made final determinations of dumping and subsidizing respecting aluminum extrusions produced via an extrusion process, of alloys having metallic elements falling within the alloy designations published by The Aluminum Association commencing with 1,2,3,5,6 or 7 (or proprietary or other certifying body equivalents), with the finish being as extruded (mill), mechanical, anodized or painted or otherwise coated, whether or not worked, having a wall thickness greater than 0.5 mm, with a maximum weight per meter of 22 kilograms and a profile or cross-section which fits within a circle having a diameter of 254 mm, originating in or exported from the People's Republic of China.

For a PDF version of the Statement of Reasons, please click on the following link.

Cet Énoncé des motifs est également disponible en français. Veuillez consulter la section "Information".

This Statement of Reasons is also available in French. Please refer to the "Information" section.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- SUMMARY OF EVENTS

- PERIOD OF INVESTIGATION

- INTERESTED PARTIES

- PRODUCT DEFINITION

- CANADIAN INDUSTRY

- IMPORTS INTO CANADA

- INVESTIGATION PROCESS

- DUMPING INVESTIGATION

- SUMMARY OF RESULTS - DUMPING

- REPRESENTATIONS CONCERNING THE DUMPING INVESTIGATION

- SUBSIDY INVESTIGATION

- SUMMARY OF RESULTS - SUBSIDY

- REPRESENTATIONS CONCERNING THE SUBSIDY INVESTIGATION

- DECISION

- FUTURE ACTION

- RETROACTIVE DUTY ON MASSIVE IMPORTATIONS

- PUBLICATION

- INFORMATION

- APPENDIX 1 - SUMMARY OF MARGINS OF DUMPING AND AMOUNTS OF SUBSIDY

- APPENDIX 2 - SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR NAMED SUBSIDY PROGRAMS

- SUBSIDY PROGRAMS USED BY COOPERATIVE EXPORTERS

- SUBSIDY PROGRAMS NOT USED BY COOPERATIVE EXPORTERS

- APPENDIX 3 - SUMMARY OF FINDINGS - SECTION 20

- APPENDIX 4 - GOC POLICIES AFFECTING THE CHINESE ALUMINUM AND ALUMINUM EXTRUSIONS INDUSTRIES

SUMMARY OF EVENTS

On July 4, 2008, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) received a complaint from Almag Aluminum Inc. of Brampton, Ontario, Apel Extrusions Limited of Calgary, Alberta, Can Art Aluminum Extrusion Inc. of Brampton, Ontario, Metra Aluminum Inc. of Laval, Quebec, Signature Aluminum Canada Inc. (formerly Bon L Canada Inc.) of Richmond Hill, Ontario, Spectra Aluminum Products Ltd. of Bradford, Ontario and Spectra Anodizing Inc. of Woodbridge, Ontario (Complainants) alleging that imports of certain aluminum extrusions originating in or exported from the People's Republic of China (China) are being dumped and subsidized and causing injury to the Canadian industry.

On July 18, 2008, pursuant to subsection 32(1) of the Special Import Measures Act (SIMA), the CBSA informed the Complainants that the complaint was properly documented. The CBSA also notified the government of China (GOC) that a properly documented complaint had been received and provided the GOC with the non-confidential version of the subsidy complaint.

The Complainants provided evidence to support the allegations that aluminum extrusions from China have been dumped and subsidized. The evidence also discloses a reasonable indication that the dumping and subsidizing has caused injury or is threatening to cause injury to the Canadian industry producing these goods.

On August 13, 2008, the CBSA received written preliminary comments from the GOC concerning the evidence presented in the non-confidential version of the subsidy complaint and comments concerning the CBSA's practices in previous subsidy investigations involving China. The GOC claimed that the complaint lacks sufficient evidence to initiate a subsidy investigation on aluminum extrusions. The GOC also claimed that the complaint fails to provide supporting evidence to show that subsidies applied to the aluminum extrusions sector in China. The CBSA considered the representations made by the GOC in its analysis of whether there was sufficient evidence of subsidizing to warrant an investigation.

On August 14, 2008 consultations were held with the GOC pursuant to Article 13.1 of the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. During these consultations, the GOC made representations with respect to its views on the evidence presented in the non-confidential version of the subsidy complaint.

On August 18, 2008, pursuant to subsection 31(1) of SIMA, the President of the CBSA (President) initiated investigations respecting the dumping and subsidizing of certain aluminum extrusions from China. On the basis of the available information, the CBSA concluded that there was sufficient evidence to initiate a section 20 inquiry concurrently with the dumping and subsidy investigations to examine the degree of GOC involvement in the aluminum extrusions sector and the related impact on pricing.

Upon receiving notice of the initiation of the investigations, the Canadian International Trade Tribunal (Tribunal) started a preliminary injury inquiry into whether the evidence discloses a reasonable indication that the alleged dumping and subsidizing of certain aluminum extrusions from China have caused injury or retardation or are threatening to cause injury to the Canadian industry producing the goods. On October 17, 2008, the Tribunal determined that there is evidence that discloses a reasonable indication that the dumping and subsidizing of certain aluminum extrusions have caused injury.

On November 17, 2008, as a result of the CBSA's preliminary investigations and pursuant to subsection 38(1) of SIMA, the President made preliminary determinations of dumping and subsidizing with respect to certain aluminum extrusions originating in or exported from China.

The CBSA continued its investigations and, on the basis of the results, the President is satisfied that certain aluminum extrusions originating in or exported from China have been dumped and subsidized and that the margins of dumping and the amounts of subsidy are not insignificant. Consequently, on February 16, 2009, the President made final determinations of dumping and subsidizing pursuant to paragraph 41(1)(a) of SIMA.

The Tribunal's inquiry into the question of injury to the Canadian industry is continuing. Provisional duties will continue to be imposed on the subject goods until the Tribunal renders its decision. The Tribunal will issue its finding by March 17, 2009.

PERIOD OF INVESTIGATION

The period of investigation, with respect to dumping (Dumping POI), covered all subject goods released into Canada from July 1, 2007 to June 30, 2008.

The period of investigation, with respect to subsidizing (Subsidy POI), covered all subject goods released into Canada from January 1, 2007 to June 30, 2008.

INTERESTED PARTIES

Complainants

The Complainants are major producers of aluminum extrusions in Canada, accounting for a major proportion ofthe domestic industry for like goods.

The name and address of the Complainants are:

Almag Aluminum Inc.

22 Finley Road

Brampton, ON

L6T 1A9Apel Extrusions Limited

7929-30 Street S.E.

Calgary, AB

T4C 1R7CanArt Aluminum Extrusion Inc.

85 Parkshore Drive

Brampton, ON

L6T 5M1Metra Aluminum Inc.

2000 Fortin Boulevard

Laval, QC

R7S 1P3Signature Aluminum Canada Inc.

500 Edward Avenue

Richmond Hill, ON

L4C4Y9Spectra Aluminum Products Ltd.

95 Reagens Industrial Parkway

Bradford, ON

L3Z2A4Spectra Anodizing Inc.

201 Hanlan Rd

Woodbridge, ON

L4L 3R7Three other producers of the like goods, Extrudex Aluminum, Daymond Aluminum and Kaiser Aluminum Canada Ltd. provided letters supporting the complaint.

Exporters

At the initiation of the investigations, the CBSA had identified 261 potential exporters of subject goods from customs import documentation and from the complaint.

The CBSA sent a Dumping Request for Information (RFI) and Subsidy RFI to each of the identified potential exporters of the goods

As part of the CBSA's section 20 inquiry, the CBSA also sent section 20 RFIs to each of the identified potential exporters and producers of the goods located in China.

While many of the export sales from China appear to involve international vendors and trading companies, in most instances the goods are shipped directly to Canada from China and the Chinese manufacturer is considered to be the exporter of the goods. However, some goods originating from China may be shipped to an intermediary country, such as the United States of America (USA) and subsequently exported to Canada. In these situations, the exporter of the goods is generally located in the intermediary country.

Complete and timely responses to the CBSA's dumping RFI were received from seven exporters, including six exporters located in China as well as one exporter located in the USA which is exporting goods originating from China to Canada. The six exporters located in China also provided complete and timely responses to the section 20 inquiry RFI and the subsidy RFI.

After the dumping and subsidy preliminary determinations on November 17, 2008, the CBSA conducted on-site verifications at the end of November and early December 2008 with these six exporters, as follows:

Kam Kiu Aluminum Extrusion Co., Ltd.

Press Metal International Ltd. (China)

Panasia Aluminum (China) Limited

Pingguo Asia Aluminum Co., Ltd.

Guangdong Weiye Aluminum Factory Co Ltd.

Guangdong Jianmei Aluminum Profile Factory Co., Ltd.

During the course of the on-site verification with one of the Chinese exporters, Pingguo Asia Aluminum Co., Ltd. (Pingguo), there were issues with respect to the accuracy and reliability of their information. As a result, this exporter was considered non-cooperative for purposes of the final determinations.

Another Chinese exporter, Press Metal International Ltd. (China) (PMI), cooperated in the dumping verification but failed to provide requested information and documentation relating to the subsidy verification. For purposes of the subsidy final determination, this exporter was considered non-cooperative.

The other four Chinese exporters fully cooperated during the on-site dumping and subsidy verifications.

In addition, during the course of the investigation, desk audits were performed by the CBSA on a number of exporter RFI submissions, including late exporter submissions received after the deadline date. Three Chinese exporters provided complete dumping and subsidy RFI responses and fully cooperated during these desk audits for purposes of the final determinations. A desk audit was also performed by the CBSA on one exporter located in the USA, which was exporting goods originating from China to Canada through two subsidiaries. This exporter also provided complete dumping RFI responses and fully cooperated for purposes of the investigation. These additional cooperating exporters are:

China Square Industrial Limited (China)

Guangya Group - Foshan Guangcheng Aluminum Co. Ltd. (China)

Guangya Group - Guang Ya Aluminum Industries Co. Ltd. (China)

Hunter Douglas Designer Shades (USA)

Hunter Douglas Window Fashions (USA)

Several other exporters and trading companies provided incomplete responses to the CBSA's dumping, subsidy, or section 20 RFIs, and their information will not be taken into consideration for purposes of the investigations.

Importers

At the initiation of the investigations, the CBSA identified 535 potential importers of subject goods based on a review of customs import documentation and information provided in the complaint.

The CBSA sent an RFI to all potential importers of the goods. Responses to the CBSA's importer RFI were received from 43 importers.

There may be instances where the importer in Canada for SIMA purposes may be a different party than the importer of record. For certain transactions involving non-resident importers, the CBSA examined available information concerning the importations for purposes of identifying the importer in Canada.

Government of China

For the purposes of these investigations "Government of China" refers to all levels of government, i.e. federal, central, provincial/state, regional, municipal, city, township, village, local, legislative, administrative or judicial, singular, collective, elected or appointed. It also includes any person, agency, enterprise, or institution acting for, on behalf of, or under the authority of any law passed by, the government of that country or that provincial, state or municipal or other local or regional government.

At the initiation of the investigations, the CBSA sent a subsidy and a section 20 RFI to the GOC. While the GOC provided a substantially complete response to the section 20 RFI, the GOC's subsidy response was found to be incomplete and was not used for the preliminary determination.

During the final stage of the investigation, after being advised by the CBSA that its original subsidy RFI response was incomplete, the GOC provided additional subsidy information. However, this additional information was filed very late in the investigation, which left the CBSA insufficient time to analyze and verify the information before the legislated final determination date. The GOC was advised that the information was not submitted in a timely fashion and that its subsidy information would not be used for purposes of the investigation. Additional details on this matter are provided subsequently in this report under "Subsidy Investigation".

Surrogate Countries

As part of the CBSA's section 20 inquiry, an RFI was also sent to producers in India, Malaysia, Mexico and Chinese Taipei, which are not subject to the present dumping investigation. No responses to these RFIs were received.

PRODUCT DEFINITION

For the purpose of these investigations, the subject goods are defined as:

"Aluminum extrusions produced via an extrusion process, of alloys having metallic elements falling within the alloy designations published by The Aluminum Association commencing with 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 or 7 (or proprietary or other certifying body equivalents), with the finish being as extruded (mill), mechanical, anodized or painted or otherwise coated, whether or not worked, having a wall thickness greater than 0.5 mm, with a maximum weight per meter of 22 kilograms and a profile or cross-section which fits within a circle having a diameter of 254 mm, originating in or exported from the People's Republic of China."

Additional Product Information 1

Extrusion is the process of shaping heated material by forcing it through a shaped opening in a die with the material emerging as an elongated piece with the same profile as the die cavity. For greater clarity, the subject goods do not include goods made by the process of impact extrusion or cold extrusion. Impact (or cold) extrusion is commonly used to make collapsible tubes such as toothpaste tubes or cans usually using soft materials such as aluminum, lead and tin. Usually a small shot of solid material is placed in the die and is impacted by a ram, which causes cold flow in the material. Impact (or cold) extrusion is not performed by the same machinery or using the same inputs as the extrusion operations of the Complainants.

Alloys are metals composed of more than one metallic element. Alloys used in aluminum extrusions contain small amounts (usually less than five percent) of elements such as copper, manganese, silicon, magnesium, or zinc which enable characteristics such as corrosion resistance, increased strength or improved formability to be imparted to the major metallic element, aluminum. Aluminum alloys are produced to specifications in "International Alloy Designations and Chemical Composition Limits for Wrought Aluminum and Wrought Aluminum Alloys" published by The Aluminum Association. These specifications have equivalent designations issued by other certifying bodies such as the International Standards Organization (ISO).

All aluminum extrusions are produced as either hollow or solid profiles. Hollow profile extrusions generally cost more to produce and obtain higher prices than solid profile extrusions. Extrusions are often produced in standard shapes such as bars, rods, pipes and tubes, angles, channels and tees but they are also produced in customized shapes.

In addition to 'as extruded' or mill finish, extrusions can be finished mechanically by polishing, buffing or tumbling. Extrusions can have anodized finishes applied by means of an electro-chemical process that forms a durable, porous oxide film on the surface of the aluminum. Also, they can be finished with liquid or powder paint coatings utilizing an electrostatic application process.

The ability to produce the full range of profiles is determined by the extrusion and ancillary equipment. The Complainants cannot produce extrusions having a wall thickness less than 0.5 mm or a weight greater than 22 kg per meter or a cross-section larger than would be enclosed within a 254 mm diameter circle.

Working or fabricating extrusions includes any operation performed other than mechanical, anodized, painted or other finishing, prior to utilization of the extrusion in a finished product. These can include precision cutting, machining, punching and drilling.

Aluminum extrusions are widely used in many end-use applications that span numerous market sectors. The main end-use sectors for aluminum extrusions are building and construction, transportation, and engineered products. Uses for aluminum extrusions in the building and construction industry cover a wide range of products, including windows, doors, railings, bridges, light poles, high-rise curtainwalls, framing members, and other various structures. Uses for aluminum extrusions in the transportation industry include parts for automobiles, buses, trucks, trailers, rail cars, mass transit vehicles, recreational vehicles, aircraft, and aerospace. Aluminum extrusions are also used in many consumer and commercial products, including, air conditioners, appliances, furniture, lighting, sports equipment, electrical power units, heat sinks, machinery and equipment, food displays, refrigeration, medical equipment, and laboratory equipment.2

Production Process 3

While details may vary from producer to producer, the process by which extrusions are produced is essentially the same for all.

The intended use of the product in which the aluminum extrusion will be applied determines the specifications for the extrusion. Machinability, finish and environment of use will determine the alloy to be extruded. The function of the profile will determine its design and that of the die that shapes it.

The extrusion process begins with an aluminum billet. The billet must be softened by heat prior to extrusion. The heated billet is placed into the extrusion press, a powerful hydraulic device wherein a ram pushes a dummy block that forces the softened metal through a precision opening known as a die, to produce the desired shape. This simplified description of the process is known as direct extrusion, which is the most common method in use today. Indirect extrusion is a similar process. In the direct extrusion process, the die is stationary and the ram forces the alloy through the opening in the die. In the indirect process, the die is contained within the hollow ram, which moves into the stationary billet from one end, forcing the metal to flow into the ram, acquiring the shape of the die as it does so.

The aluminum billet may be a solid or hollow form, commonly cylindrical, and is the length charged into the extrusion press container. It is usually a cast product but may be a wrought product or powder compact. Often it is cut from a longer length of alloyed aluminum known as a log.

The billet and extrusion tools are preheated (softened) in a heating furnace. The melting point of aluminum varies with the purity of the metal but is approximately 1,220 Fahrenheit (660° Centigrade). Extrusion operations typically take place with billet heated to temperatures in excess of 700° F (375° C), and depending upon the alloy being extruded, as high as 930°F (500° C).

The actual extrusion process begins when the ram starts applying pressure to the billet within the container. Various hydraulic press designs are capable of exerting anywhere from 100 tons to 15,000 tons of pressure. This pressure capacity of a press determines how large an extrusion it can produce. The extrusion size is measured by its largest cross-sectional dimension, sometimes referred to as its fit within a circumscribing circle diameter.

As pressure is first applied, the billet is crushed against the die, becoming shorter and wider until its expansion is restricted by full contact with the container walls. Then, as the pressure increases, the soft (but still solid) metal has no place else to go and begins to squeeze through the shaped orifice of the die to emerge on the other side as a fully formed extrusion or profile.

About 10 percent of the billet, including its outer skin, is left behind in the container. The completed extrusion is cut off at the die and the remainder of the metal is removed to be recycled. After it leaves the die, the still-hot extrusion may be quenched, mechanically treated and aged.

Classification of Imports

The aluminum extrusions subject to this complaint are normally imported into Canada under the following 34 Harmonized System (HS) classification numbers:

- 7604.10.11.10

- 7604.10.11.90

- 7604.10.12.11

- 7604.10.12.19

- 7604.10.12.21

- 7604.10.12.22

- 7604.10.12.23

- 7604.10.12.24

- 7604.10.12.29

- 7604.10.20.11

- 7604.10.20.19

- 7604.10.20.21

- 7604.10.20.29

- 7604.10.20.30

- 7604.21.00.10

- 7604.21.00.20

- 7604.29.11.10

- 7604.29.11.90

- 7604.29.12.11

- 7604.29.12.19

- 7604.29.12.21

- 7604.29.12.22

- 7604.29.12.23

- 7604.29.12.24

- 7604.29.12.29

- 7604.29.20.11

- 7604.29.20.19

- 7604.29.20.21

- 7604.29.20.29

- 7604.29.20.30

- 7608.10.00.10

- 7608.10.00.90

- 7608.20.00.10

- 7608.20.00.90

This listing of HS codes is for convenience of reference only. Refer to the product definition for authoritative details regarding the subject goods.

CANADIAN INDUSTRY

The Canadian industry for aluminum extrusions is comprised of the following companies:

Almag Aluminum Inc. of Brampton, Ontario,

Apel Extrusions Limited of Calgary, Alberta,

Can Art Aluminum Extrusion Inc. of Brampton, Ontario,

Daymond Aluminum of Chatham, Ontario,

Extrudex Aluminum of Woodbridge, Ontario,

Indalex Aluminum Solutions Group of Mississauga, Ontario,

Kaiser Aluminum Canada Ltd of London, Ontario,

Kawneer Company Canada Ltd of Scarborough, Ontario,

Kromet International Inc. of Cambridge, Ontario,

Metra Aluminum Inc. of Laval, Quebec,

Signature Aluminum Canada Inc. (formerly Bon L Canada Inc.) of Richmond Hill, Ontario,

Spectra Aluminum Products Ltd. of Bradford, Ontario,

Spectra Anodizing Inc. of Woodbridge, Ontario.

IMPORTS INTO CANADA

During the final phase of the investigations, the CBSA refined the estimated volume of imports based on information from its internal Customs Commercial Systems, Customs import entry documentation and other information received from exporters, importers and other parties.

The following table presents the CBSA's estimates of imports of certain aluminum extrusions for purposes of the final determinations:

Imports of Certain Aluminum Extrusions (July 1, 2007 - June 30, 2008)

Imports into Canada % of Total Imports China 44% U.S.A. 48% All Other Countries 8% Total Imports 100%

INVESTIGATION PROCESS

Regarding the dumping investigation, information was requested from known and possible exporters, vendors and importers, concerning shipments of certain aluminum extrusions released into Canada during the Dumping POI of July 1, 2007 to June 30, 2008. Information related to potential actionable subsidies was requested from known and possible exporters and the GOC concerning financial contributions made to producers or exporters of aluminum extrusions of Chinese origin released into Canada during the Subsidy POI of January 1, 2007 to June 30, 2008.

In addition, known and possible exporters and producers of the goods along with the GOC were requested to respond to the section 20 RFI for the purposes of the section 20 inquiry. Aside from the aforementioned exporters which provided complete information and fully cooperated for purposes of the final determinations, several exporters and trading companies provided incomplete or deficient RFI replies. Information from these companies has not been taken into consideration for purposes of the final determinations.

The GOC provided a substantially complete response to the section 20 RFI by the extended due date. As explained previously, after being advised by the CBSA that its original subsidy response was incomplete and would not be used for purposes of the preliminary determination, the GOC provided additional supplementary subsidy information. However, this additional information was filed very late in the investigation, which left the CBSA insufficient time to analyze and verify the information before the legislated final determination date.

The GOC was advised that the information was not submitted in a timely fashion and that its subsidy information would not be used for purposes of the investigation. Notwithstanding that the GOC's subsidy information was not used, the CBSA has established individual amounts of subsidy for the cooperative Chinese exporters under a ministerial specification.

In summary, 56 potential subsidy programs were investigated and the CBSA determined that 15 of the potential subsidy programs were conferring benefits to the seven cooperative Chinese exporters during the Subsidy POI.

As part of the final stage of the investigations, case briefs and reply submissions were provided by the legal representatives of the GOC, the Complainants, three Chinese exporters and one U.S. exporter of Chinese origin goods.

DUMPING INVESTIGATION

Section 20 Inquiry

Section 20 of SIMA may be applied to determine the normal value of goods in a dumping investigation where certain conditions prevail in the domestic market of the exporting country. In the case of a prescribed country under paragraph 20(1)(a) of SIMA4, it is applied where, in the opinion of the President, domestic prices are substantially determined by the government of that country and there is sufficient reason to believe that they are not substantially the same as they would be if they were determined in a competitive market. Where section 20 is applicable, the normal value of goods is not determined based on domestic prices or costs in that country.

For purposes of a dumping investigation, the CBSA proceeds on the presumption that section 20 of SIMA is not applicable to the sector under investigation unless there is evidence to suggest otherwise. The President may form an opinion where there is sufficient information that the conditions set forth in paragraph 20(1)(a) of SIMA exist in the sector under investigation.

The mere existence of substantial domestic price determination by the government would be insufficient to apply section 20 of SIMA. The CBSA is also required to examine the price effect resulting from substantial government determination of domestic prices and whether there is sufficient information on the record for the President to have a reason to believe that the resulting domestic prices are not substantially the same as they would be in a competitive market.

The Complainants requested that section 20 be applied in the determination of normal values due to the alleged existence of the conditions set forth in paragraph 20(1)(a) of SIMA. The Complainants provided information to support these allegations concerning the aluminum extrusions sector in China.

At the initiation of the investigation, the CBSA had sufficient evidence, supplied by the Complainants, and from its own research, to support the initiation of a section 20 inquiry. The information indicated that the prices of aluminum extrusions in China have been substantially determined, indirectly, by various GOC industrial policies regarding the aluminum and aluminum extrusions industries and by export restrictions and tax changes for aluminum and aluminum extrusions.

Accordingly, the CBSA, at the initiation of the dumping investigation, sent section 20 RFIs to 160 known exporters of aluminum extrusions in China, as well as to the GOC requesting detailed information related to the aluminum extrusions sector. In response to the section 20 inquiry and the relevant questionnaires, the CBSA received substantially complete and verifiable responses from eight Chinese exporters and from the GOC.

The eight cooperative exporters represent approximately 41% of the total exports to Canada of subject goods, by volume during the Dumping POI. These companies represent a far smaller proportion of the Chinese domestic aluminum extrusions industry, which the GOC has indicated is comprised of over 460 producers5. A section 20 inquiry assesses the domestic industry sector as a whole. As such, the review of the aluminum extrusions sector is not limited to an examination of the information provided by the cooperative exporters.

In addition, the CBSA has obtained information from other sources such as previous CBSA reports, market intelligence reports, public industry reports, newspaper and internet articles as well as other government documents.

For purposes of the preliminary determination, the President considered the cumulative effect that the GOC's measures have exerted on the aluminum extrusions sector in China. The information indicated that the wide range and material nature of the GOC measures have resulted in significant influences on the aluminum industry, including the aluminum extrusions sector, through means other than competitive market forces.

Accordingly, the President formed the opinion that domestic prices in the aluminum extrusions sector in China are substantially determined by the GOC and there is sufficient reason to believe that the domestic prices are not substantially the same as they would be in a competitive market.

The CBSA continued with the section 20 inquiry during the final stage of the investigation.

Taking together all the information obtained during the course of the section 20 inquiry, the President has affirmed the opinion made at the preliminary determination that domestic prices in the aluminum extrusions sector in China are substantially determined by the GOC and there is sufficient reason to believe that the domestic prices are not substantially the same as they would be in a competitive market.

Appendix 3 provides a summary of the findings considered by the President in affirming this section 20 opinion.

Normal Value

Normal values are generally based on the domestic selling prices of the goods in the country of export, or on the full cost of the goods including administrative, selling and all other costs plus a reasonable amount for profit.

For purposes of the final determination, the CBSA has concluded that normal values could not be determined on the basis of domestic selling prices in China or on the full cost of goods plus profit, as the CBSA has affirmed the opinion made at the preliminary determination that the conditions of section 20 exist in the aluminum extrusions sector in China.

Where section 20 conditions exist, the CBSA will establish whether normal values can be determined using the selling price, or the total cost and profit, of like goods sold by producers in a surrogate country designated by the President pursuant to paragraph 20(1)(c) of SIMA. However, no surrogate country producers provided the information necessary to determine normal values in accordance with this provision.

Alternatively, normal values may be determined on a deductive basis starting with an examination of the prices of imported goods sold in Canada, from a surrogate country designated by the President, pursuant to paragraph 20(1)(d) of SIMA. However, sufficient information was not submitted by importers in response to the importer RFI to allow for the application of paragraph 20(1)(d).

Accordingly, the CBSA has used an alternate method to determine normal values for cooperative exporters for purposes of the final determination, pursuant to a ministerial specification under subsection 29(1) of SIMA.

In the complaint, the Complainants submitted that India is an appropriate surrogate country to be used for the calculation of normal values, since it is a major producer of aluminum extrusions and has comparable wage rates. Additionally, the cost of the aluminum raw material input to extruders in India should reflect international, market economy prices.

The CBSA finds that the Complainants' selection of India for purposes of establishing costs for use in determining normal values is reasonable since both India and China are developing countries and the President has designated India as the surrogate country for China previously.

As the cost of aluminum accounts for such a significant portion of the costs of producing aluminum extrusions, the CBSA's starting point for determining normal values is based on the monthly average settlement price of aluminum as reported on the London Metal Exchange (LME). The LME is the largest futures and contract market for various metals including aluminum and is a global reference pricing source for purchases and sales of such goods.

Amounts have been added to the LME prices for the cost to convert the aluminum into a finished aluminum extrusion product, using information provided by the Complainants, adjusted to reflect costs in India as a surrogate. Separate conversion costs have been established to account for cost differences relating to product that is "mill finished" and product that undergoes additional finishing, such as anodizing or painting. An amount for administrative, selling and all other costs has also been added using information provided by the Complainants, again adjusted to reflect costs in India.

Lastly, an amount for profit has been added to these costs based on the profit earned by the Complainants on domestic and export sales of the like goods for the 2007 calendar year in order to determine normal values for the cooperative exporters.

Export Price

The export price of goods sold to importers in Canada is generally calculated pursuant to section 24 of SIMA based on the lesser of the adjusted exporter's sale price for the goods or the adjusted importer's purchase price. These prices are adjusted where necessary by deducting the costs, charges, expenses, duties and taxes resulting from the exportation of the goods as provided for in subparagraphs 24(a)(i) to 24(a)(iii) of SIMA.

In the case of sales to related importers in Canada, the CBSA performs a reliability test of the export price under section 24 of SIMA. If the export price under section 24 of SIMA is found not to be reliable, then section 25 of SIMA would be used to determine export prices.

For purposes of the final determination, export prices for the cooperative exporters were determined using reported export pricing data provided by the exporters and importers of the goods. For non-cooperative exporters, the export price was determined based on the import pricing data available from customs' information.

Export sales to Canada involving third parties (i.e. intermediaries) which are related to the exporter

For goods shipped directly to Canada from China, the exporter for SIMA purposes is usually the Chinese producer of the goods (i.e. it is usually the producer which knowingly releases the goods for direct shipment to Canada). However, there are situations where the Chinese producer has a related trading company/sales office (i.e., an intermediary) located elsewhere in China or in other jurisdictions which is involved in the export sale of goods to Canada. While the goods are shipped directly to Canada from the producer's facilities, frequently, there is an internal sale/transfer price between the Chinese producer and the related intermediary.

Under section 24 of SIMA, export price is generally based on the lesser of the exporter's selling price and the importer's purchase price. For certain cooperating exporters, the sale/transfer price between the producer and the related intermediary was used for purposes of estimating export price at the time of the preliminary determination.

This issue was reconsidered as part of the final stage of the investigation. This included an examination of the relationship between the producer and related intermediary and the manner in which the sales to Canada were made during the POI. The investigation revealed that the producer and intermediary are part of the same corporate group and meet the definition of "associated persons" in SIMA. It was found that the intermediary and producer did not deal with each other at arm's length, and in fact were operating as a single business entity on sales of subject goods to Canada during the POI. That is, the related intermediary was acting to facilitate the producer's sale of goods to the Canadian market and was not acting in its own commercial interest or assuming the commercial risk associated with such sales.

Therefore, for purposes of the final determination, where the cooperating Chinese producers were selling to Canada through a related intermediary and the above-noted conditions were met, the sale/transfer price between the producer and related intermediary was not taken into consideration. Rather, the selling price from the related intermediary to the importer in Canada was used as the exporter's selling price under section 24 of SIMA.

Results of Dumping Investigation

The CBSA determined margins of dumping for each of the cooperative exporters by comparing normal values with the export prices. When the export price is less than the normal value, the difference is the margin of dumping.

For the exporters that did not respond to the RFI, or provided an incomplete or deficient submission, the normal values were determined under a ministerial specification pursuant to section 29 of SIMA based on the export price as determined under section 24, 25 or 29 of SIMA, plus an amount equal to 101% of that export price, which represents the highest margin of dumping found for a cooperative exporter during the investigation, excluding anomalies.

The determination of the volume of dumped goods was calculated by taking into consideration each exporter's net aggregate dumping results. Where a given exporter has been determined to be dumping on an overall or net basis, the total quantity of exports attributable to that exporter (i.e. 100%) is considered dumped. Similarly, where a given exporter's net aggregate dumping results are zero, then the total quantity of exports deemed to be dumped by that exporter is zero.

In calculating the weighted average margin of dumping, the overall margins of dumping found in respect of each exporter were weighted according to each exporter's volume of certain aluminum extrusions exported to Canada during the Dumping POI.

Based on the preceding, 99.8% of the subject aluminum extrusions from China were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 72.6%, as a percentage of export price.

Under Article 15 of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Anti-dumping Agreement, developed countries are to give regard to the special situation of developing country members when considering the application of anti-dumping measures under the Agreement. Possible constructive remedies provided for under the Agreement are to be explored before applying anti-dumping duty where they would affect the essential interests of developing country members. As China is listed on the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) List of Official Development Assistance (ODA) Aid Recipients 6 maintained by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the President recognizes China as a developing country for purposes of actions taken pursuant to SIMA.

Accordingly, the obligation under Article 15 of the WTO Anti-dumping Agreement was met by providing the opportunity for exporters to submit price undertakings. In this particular investigation, the CBSA did not receive any proposals for undertakings from any of the identified exporters.

Dumping Results by Exporter

Specific margin of dumping details relating to each of the exporters that cooperated in the CBSA's dumping investigation are as follows:

Taishan City Kam Kiu Aluminum Extrusion Co., Ltd. (China)

Taishan City Kam Kiu Aluminum Extrusion Co., Ltd. (Kam Kiu) is a 100% foreign owned, limited liability company incorporated in Hong Kong. Kam Kiu uses primary aluminum to cast its own billets and the special tooled precision dies are made by Kam Kiu to produce aluminum extrusions according to customer requirements. The CBSA conducted on-site verification of Kam Kiu's RFI responses from December 4 to December 12, 2008.

Exports to Canada are sold via Kam Kiu's related trader and are shipped from China to customers in Canada. For the final determination, export prices were determined pursuant to section 24 of SIMA, on the basis of the exporter's selling price from Kam Kiu's related trader, adjusted to take into account all costs, charges and expenses incurred in preparing the goods for shipment to Canada and resulting from the exportation and shipment of the goods.

Margin of Dumping

The total normal value was compared with the total export price for all subject aluminum extrusions imported into Canada during the Dumping POI. It was found that the goods exported by Kam Kiu were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 27.8%, expressed as a percentage of export price.

Press Metal International Ltd. (China)

Press Metal International Ltd. (PMI) is a 100% foreign owned company with the parent company located in Malaysia. PMI is an aluminum extruder and has a related raw material supplier of aluminum ingots. The CBSA conducted on-site verification of PMI's RFI responses, from November 24 to November 28, 2008, and its related raw material supplier's responses from December 8 to December 9, 2008.

Exports to Canada are sold and shipped directly to several unrelated importers in Canada. For the final determination, export prices were determined pursuant to section 24 of SIMA, based on the exporter's selling price, adjusted to take into account all costs, charges and expenses incurred in preparing the goods for shipment to Canada and resulting from the exportation and shipment of the goods.

Margin of Dumping

The total normal value was compared with the total export price for all subject aluminum extrusions imported into Canada during the Dumping POI. It was found that the goods exported by PMI were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 35.2%, expressed as a percentage of export price.

PanAsia Aluminum (China) Limited

PanAsia Aluminum (China) Limited (PanAsia) is a Foreign-Invested Enterprise (FIE) and manufacturer of the subject goods exported to Canada. It produces aluminum extrusions for the domestic and various export markets at its production facility located in Zengcheng City in the Chinese province of Guangdong. The CBSA conducted on-site verification of PanAsia's RFI responses from November 24 to November 28, 2008.

Exports to Canada are sold through an affiliated trading company located in Macau and are shipped directly from China to related subsidiaries and unrelated companies in Canada.

In the case of sales to related importers in Canada, the CBSA performs a reliability test of the export price under section 24 of SIMA. If the export price under section 24 of SIMA is found not to be reliable, then section 25 of SIMA would be used to determine export prices. The results of the reliability test for sales made by PanAsia's affiliated trading company to a related subsidiary in Canada revealed that the section 24 export prices to this related subsidiary were unreliable for SIMA purposes. As a result, for all sales to this related subsidiary, the export prices were determined in accordance with section 25 of SIMA, based on the importer's resale prices in Canada less all costs incurred in importing and selling the goods, and an amount for profit based on the profit earned by vendors of like goods in Canada.

-

Export prices for all other sales to Canada were determined pursuant to section 24 of SIMA, on the basis of the exporter's selling price from PanAsia's affiliated trading company, adjusted to take into account all costs, charges and expenses incurred in preparing the goods for shipment to Canada and resulting from the exportation and shipment of the goods.

Margin of Dumping

The total normal value was compared with the total export price for all subject aluminum extrusions imported into Canada during the Dumping POI. It was found that the goods exported by PanAsia were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 31.4%, expressed as a percentage of export price.

Guangdong Weiye Aluminum Factory Co., Ltd. (China)

Guangdong Weiye Aluminum Factory Co., Ltd. (Weiye) is a privately owned company and is a manufacturer of aluminum extrusions and stainless steel products. Weiye develops and manufactures a wide range of aluminum extrusions for various industries (such as construction, electronic, IT, sporting goods). The company purchases 100% of its raw materials from several domestic suppliers. The CBSA conducted on-site verification of Weiye's RFI responses from December 1 to December 5, 2008.

Exports to Canada are sold and shipped directly to multiple unrelated companies in Canada. For the final determination, export prices were determined pursuant to section 24 of SIMA, based on the exporter's selling price, adjusted to take into account all costs, charges and expenses incurred in preparing the goods for shipment to Canada and resulting from the exportation and shipment of the goods.

Margin of Dumping

The total normal value was compared with the total export price for all subject aluminum extrusions imported into Canada during the Dumping POI. It was found that the goods exported by Weiye were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 42.4%, expressed as a percentage of export price.

Guangdong Jianmei Aluminum Profile Factory Co., Ltd. (China)

Guangdong Jianmei Aluminum Profile Factory Co., Ltd. (Jianmei) is a privately-owned limited liability company. Jianmei has two production plants that produce different types of aluminum profiles, including thermal break series, curtain wall series, doors and windows series and other profiles. Jianmei purchases aluminum ingots and melts them into aluminum billets. The CBSA conducted on-site verification of Jianmei's RFI responses from December 1 to December 5, 2008.

Exports to Canada are sold by JMA (Hong Kong) Company Limited (JMA(HK)), an associated trading company, and are shipped directly from China to multiple unrelated companies in Canada. For the final determination, export prices were determined pursuant to section 24 of SIMA, based on the exporter's selling price from Jianmei's associated trading company, JMA (HK), adjusted to take into account all costs, charges and expenses incurred in preparing the goods for shipment to Canada and resulting from the exportation and shipment of the goods.

Margin of Dumping

The total normal value was compared with the total export price for all subject aluminum extrusions imported into Canada during the Dumping POI. It was found that the goods exported by Jianmei were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 28.5%, expressed as a percentage of export price.

China Square Industrial Limited (China)

China Square Industrial Limited (China Square) is a limited liability company, and includes a Hong Kong based parent company responsible for export sales, and production facilities in China (Zhaoqing). The company produces a range of aluminum extrusion products.

Exports to Canada of subject goods are shipped directly from China to two unrelated companies in Canada. For the final determination, export prices were determined pursuant to section 24 of SIMA, based on the exporter's selling price, adjusted to take into account all costs, charges and expenses incurred in preparing the goods for shipment to Canada and resulting from the exportation and shipment of the goods.

Margin of Dumping

The total normal value was compared with the total export price for all subject aluminum extrusions imported into Canada during the Dumping POI. The subject goods exported by China Square were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 1.7%, expressed as a percentage of export price.

Guangya Group (China)

The CBSA received dumping and subsidy RFI responses from the Guangya Group, which is comprised of Guangya Aluminum Industries Co., Ltd. (Guangya), Foshan Guangcheng Aluminum Co., Ltd. (Guangcheng), Guangya Aluminum Industries (Hong Kong) Ltd. (Guangya HK) and Guangcheng Aluminum Industries (U.S.A.) Inc. (Guangcheng US). The Group produces and sells a wide range of aluminum products for architecture and industrial markets in China as well as for export.

-

During the POI, exports to Canada were produced and shipped from China by Guangya and Guangcheng, and sold through one of the four Guangya Group companies (i.e. Guangya, Guangcheng, Guangya HK, or Guangcheng US) to multiple unrelated companies in Canada.

As such, for the final determination, export prices were determined pursuant to section 24 of SIMA, based on the exporter's selling price, adjusted to take into account all costs, charges and expenses incurred in preparing the goods for shipment to Canada and resulting from the exportation and shipment of the goods.

Margin of Dumping

The total normal value was compared with the total export price for all subject aluminum extrusions imported into Canada during the dumping POI, separately for Guangcheng and Guangya. The results reveal that the subject goods exported to Canada by Guangcheng were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 33.8%, expressed as a percentage of export price. The subject goods exported to Canada by Guangya were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 40.4%, expressed as a percentage of export price.

Hunter Douglas (United States)

The Hunter Douglas group of companies is privately owned, and part of a wider corporate group, Hunter Douglas NV, located in the Netherlands.

The Hunter Douglas group includes three USA subsidiaries, two of which are distributors and exporters of Chinese origin aluminum extrusions to Canada - Hunter Douglas Window Fashions (HDWF) and Hunter Douglas Designer Shades (HDDS).

Hunter Douglas Window Coverings Inc (HDWC), the third party in this Hunter Douglas group, sources subject goods from Chinese manufacturers and paints them. Both HDWF and HDDS then purchase the painted subject goods from HDWC and sell them to USA and Canadian fabricators. The fabricators then use the subject goods in the manufacture of window shades and treatments based on the specifications of their dealer customers.

Both HDDS and HDWF make export sales directly from the USA to two related Canadian importers.

In the case of sales to related importers in Canada, the CBSA performs a reliability test of the export price under section 24 of SIMA. If the export price under section 24 of SIMA is found not to be reliable, then section 25 of SIMA would be used to determine export prices. The results of the reliability test for such sales made by HDDS and HDWF indicate that the section 24 export price was reliable.

Accordingly, for the final determination, export prices were determined pursuant to section 24 of SIMA, based on the exporter's selling price, adjusted to take into account all costs, charges and expenses incurred in preparing the goods for shipment to Canada and resulting from the exportation and shipment of the goods.

Margin of Dumping

The total normal value was compared with the total export price for all subject aluminum extrusions imported into Canada during the Dumping POI. The subject goods exported by HDDS were found not to be dumped. The subject goods exported by HDWF were dumped by a weighted average margin of dumping of 2.9%, expressed as a percentage of export price.

Non-Cooperative Exporters - Margin of Dumping

For non-cooperative exporters, import pricing information available from the CBSA's internal Customs Commercial Systems was used for purposes of determining export price. The normal value was determined under a ministerial specification pursuant to section 29 of SIMA, based on the export price as determined under section 24, 25 or 29 of SIMA, plus an amount equal to 101% of that export price, which represents the highest margin of dumping found for a cooperative exporter during the investigation, excluding anomalies.

SUMMARY OF RESULTS - DUMPING

Period of Investigation - July 1, 2007 to June 30, 2008

| Country | Dumped Goods as Percentage of Country Imports | Weighted Average Margin of Dumping | Country Imports as Percentage of Total Imports | Dumped Goods as Percentage of Total Imports |

| China | 99.8% | 72.6% | 43% | 43% |

REPRESENTATIONS CONCERNING THE DUMPING INVESTIGATION

Listed below are details of representations made to the CBSA with respect to the dumping investigation, including case arguments and reply submissions, from exporters, importers, the GOC and the Complainants. Following the representations on each issue is a response explaining the position of the CBSA. Since there were a number of common positions from multiple parties, the CBSA may make specific reference to only one or two parties when documenting the issue raised.

1. Grounds for Initiation and Burden of Proof

The GOC submitted that the complaint fell short of establishing a "reasonable indication" of sufficient evidence of dumping or any causal link to any injury as required under Article 5.2 of the WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement.7

Furthermore, the GOC submitted that the relevant provisions of SIMA must be construed strictly and that their application should be limited to the terms of the applicable provisions.8 As such, the GOC argued that the CBSA must interpret and apply the provisions in section 20 of SIMA in a strict manner, as this section provides an exceptional method for determining normal values.9

Chinese exporter PanAsia claimed that the CBSA's interpretation of section 20 was inconsistent with SIMA.

Another Chinese exporter, Kam Kiu, also submitted that the use of section 20 or invocation of Article 15 of China's WTO Accession Protocol does not eliminate the need for a fair comparison, and the CBSA has failed to properly interpret and apply Article 15.10 The company stated that since section 20 is an exception to the general rules, the burden of proof for invoking the exception is on those parties requesting that section 20 be applied and that the evidence provided in the complaint was not sufficient to meet this burden of proof.11

Chinese exporter Pingguo submitted that under section 20, the CBSA is required to adhere to a two-fold test: first, that domestic prices are substantially determined by the government of that country and second, that there is sufficient reason to believe that domestic prices are not substantially the same as they would be if they were determined in a competitive market.12

Furthermore, Pingguo stated that at the preliminary determination, the CBSA conclusions referred to indirect price effects by GOC industrial policies and export restrictions, whereas Pingguo proposed that more substantive analysis is necessary.

The GOC submitted that in order to demonstrate that domestic prices are substantially determined by the GOC, the evidence on the record must establish that the GOC has actively taken steps to determine prices. Consequently, the CBSA's list of indirect factors that are considered as methods a government may determine prices, cannot justify a section 20 finding. The GOC asserted that while certain measures may influence or affect prices, this is not sufficient to meet the "determine" threshold of section 20 of SIMA.13

Kam Kiu added that the CBSA cannot properly determine that SIMA section 20 conditions exist on the basis of indirect factors and general government policies.14

The GOC argued that the ordinary meaning of the words "substantially" and "determine" provide that the CBSA must establish that the GOC "determines or decides to a large extent or to a large degree" the domestic prices of aluminum extrusions in China to meet this threshold under section 20.15

The GOC also submitted that, in assessing whether or not the domestic prices are not substantially the same as they would be if they were determined in a competitive market, that the CBSA must assess all of the factors that determine prices and "net out" other causal factors that may be driving prices. The GOC submitted that the CBSA did not conduct such an analysis at the preliminary determination and simply noted that prices in China appeared lower than prevailing world prices.15

The GOC further argued that the CBSA is bound by the fundamental principles of interpretation applicable to taxation laws in Canada to the effect that "any reasonable uncertainty or factual ambiguity resulting from a lack of explicitness in the statute should be resolved in favour of the taxpayer". The GOC submitted that in the event that there is any ambiguity in section 20 of SIMA, that the interpretation that favours the GOC and the exporters should be adopted.17

The Complainants contended that section 20 of SIMA is applicable on the facts of the present investigation, indicating that the GOC policies exert sufficient influence on the aluminum extrusion industry, in China, so as to substantially determine prices of like goods and prices are not the same as they would be in a competitive market.18 The Complainants contended that:

- The GOC manipulates aluminum billet cost, the largest material cost in the production of like goods, by providing access to low cost billets;

- The GOC manipulates domestic prices by changing export taxes and rebates; and

- The GOC controls production inputs and finished like goods through its laws, guidelines and through the influence of industry groups controlled by the GOC.19

Furthermore, the Complainants responded to the issue of the various interpretations of section 20 of SIMA and cited illustrations of why the Chinese aluminum extrusion industry is not a competitive market.20

In response to definitions proposed by the GOC for section 20 terms such as "substantially" and "determines", the Complainants contended that the GOC's own definition of these words, "support the interpretation of section 20 which contemplates that indirect government actions can substantially determine (non-market) pricing".21

Regarding the GOC's suggestion that the CBSA's interpretation of SIMA relies on presumptions that "favour the taxpayer", the Complainants argued that such interpretations are based on a false premise and that SIMA's purpose is to protect the domestic industry.22 The Complainants asserted that SIMA is "economic legislation" aimed to protect Canadian industry and is thus, not a taxation statute.

CBSA Response

Absent sufficient information to the contrary, the CBSA proceeds in an anti-dumping investigation on the presumption that section 20 of SIMA does not apply to the sector under investigation. This approach follows the CBSA's section 20 policy.

The information before the CBSA at the initiation of the investigation included information contained in the complaint from Canadian industry as well as information obtained through the CBSA's own research. The CBSA's analysis of this evidence and justification for initiating a section 20 inquiry is contained in the Complaint Analysis, which was placed on the CBSA's listing of exhibits for this investigation.23

At the time of initiation, all known exporters, producers and the GOC were informed of the section 20 inquiry, requested to respond to a Request for Information and invited to provide any relevant information, evidence and arguments.

Once a section 20 inquiry is undertaken, the President may, having regard to the information obtained from the complainant, the government of the country of export, producers, exporters or any other sources of relevant information, form an opinion on the basis of fact and positive evidence that the conditions described under section 20 exist in the sector under investigation.

Regarding the sufficiency of information in the complaint to meet the threshold to initiate a section 20 inquiry, the CBSA notes that its policy with respect to the application of section 20 requires complainants to provide sufficient evidence that the conditions of section 20 exist in the relevant industry sector if they wish to base their price and cost estimates on third country information. In their complaint, the Complainants provided evidence that the section 20 conditions were met. The Complainants further provided normal values estimated on surrogate country costs and estimated costs in China.

In short, the arguments regarding the alleged insufficiency of evidence to initiate a section 20 inquiry do not specifically address or refute any of the CBSA evidence or analysis contained in its Complaint Analysis.

As in previous section 20 inquiries, the CBSA references a list of direct and indirect factors that governments may use to substantially determine prices. The CBSA's use of indirect factors is well established and the CBSA is of the opinion that such factors can result in a government's substantial determination of prices. The CBSA considered the cumulative effect that the GOC's regulatory, tax and other measures have exerted on the Chinese aluminum extrusions sector.

The information on the record discloses both the scope and nature of the GOC measures in the aluminum extrusion sector and the related impact of these measures on pricing. The CBSA is satisfied that the evidence on the administrative record for this investigation is reliable and credible. The evidence is sufficient for the President to form the opinion that the GOC is substantially determining domestic prices of aluminum extrusions in China and that there is sufficient reason to believe that these prices are not the same as they would be if they were determined in a competitive market.

2. Prices for Aluminum Extrusions

The GOC submitted that the CBSA failed to accord proper weight to the "ferociously competitive and fragmented nature of the Chinese aluminum extrusions industry and instead misdirected its analysis mainly to the state of the upstream aluminum industry in general." The GOC submitted that the primary focus of the section 20 inquiry must be specific to the aluminum extrusions industry, not generalized to the raw material production industry.24

PanAsia also submitted that the CBSA should restrict its sector review to the manufacture, production and sale of "like products." PanAsia further contended that the process used to determine whether Chinese industry sectors are non-market violates the procedure for determining market economy status agreed upon among WTO members in China's WTO Accession Protocol.25 PanAsia claimed that by relying on this flawed application, the Government of Canada is acting in violation of its WTO obligation.26

The GOC submitted that the CBSA failed to conduct a "pass-through" analysis in assessing whether or not the alleged price effects on aluminum have indeed passed-through to any downstream users of the raw materials.

The GOC argued that the same fundamental principles for determining whether or not an upstream subsidy is passed-through must be applied. In this regard, the GOC noted that the CBSA has failed to conduct any analysis to show that any benefit from any program in China relating to aluminum has contributed to or benefited producers of aluminum extrusions or had a material impact on aluminum prices paid by aluminum extrusions producers.27

The GOC further stated that the CBSA completely failed to note that approximately half of the aluminum consumed by the aluminum extrusions sector is imported and not produced in China and that imports of aluminum into China rose during the POI, which would not be possible if market prices were artificially suppressed by government interference.28

CBSA Response

Given that the cost of raw aluminum constitutes a high percentage of the cost of aluminum extrusions, the CBSA's section 20 analysis appropriately considered the impact of the GOC's involvement in the upstream industry. The evidence on the record and the CBSA's analysis demonstrates that GOC actions led to the price of aluminum in China being substantially lower than the prices found in the rest of the world during the POI, for what is essentially a commodity product. In both the preliminary and final determinations, the CBSA has demonstrated that the prices paid by cooperative exporters for aluminum (i.e. downstream users) are consistent with this conclusion.

-

Regarding the GOC's assertion that "half of the aluminum consumed by the aluminum extrusions sector is imported and not produced in China," the CBSA notes that amongst the eight cooperative Chinese exporters, only one exporter imported marginal amounts of aluminum during the entire dumping POI; the rest relied entirely upon domestically produced aluminum. The CBSA further notes that the GOC's support for their assertion refers to the fact that aluminum producers in China import half of their alumina requirements, not that aluminum extruders import half of their aluminum.

However, evidence on the record regarding alumina in China indicates that imports of alumina have been decreasing and amounted to approximately 20% of Chinese consumption in 2007.29 The CBSA did not analyze the impact GOC measures would have on the price of alumina in China since alumina is not a direct raw material for aluminum extrusions and, to the extent that the price of alumina is affected by GOC policies, this effect would be reflected in the price of aluminum in China which was already included in the analysis.

Furthermore, the CBSA does not disagree with the GOC's statement that extensive import penetration and rising import penetration for aluminum would not be possible in the POI if the Chinese market prices were artificially suppressed by government influence. Indeed, the evidence on the record demonstrates that imports of aluminum shrank over 60% from 2006 to 2007, and further demonstrates that imports of aluminum comprised less than 1% of China's domestic consumption of primary aluminum in 2007.30 These facts demonstrate that aluminum import penetration was not possible, and was even significantly eroding during the POI, given the artificially suppressed government price of aluminum in China. These facts also support the analysis that the low price of aluminum in China has "passed through" to aluminum extruders in that virtually no imported aluminum was available in China during the POI.

The CBSA's policy regarding the application of section 20 provides that the President may, having regards to the evidence on the record, form an opinion that the conditions described under section 20 exist in the sector under investigation and reflects Canada's implementation of its rights and obligations under the WTO.

3. Assessment of GOC Policies

-

The GOC submitted that the CBSA has misconstrued the nature of the GOC "policies" it has examined, and reiterated its position that the Industrial Development Policy for the Aluminum Industry and the Special development Plan for Aluminum Industry Development have not been formally promulgated by the State Council and are not in effect.

The GOC further argued that, even if these policies had been formally adopted, they are at most "aspirational expressions of the GOC's hopes for an industry".31 The GOC further argued that the CBSA failed to properly consider the stated objective and intent of these industrial policies, in that they are directed towards concerns such as the environmental impact of inefficient aluminum smelters in China.

In response to the GOC, the Complainants contended that China remains a country where the central government is an authority whose mere "aspirations" have more effect than actively enforced laws in other countries.

The GOC also contested the CBSA's listed restrictions, minimum standards and thresholds for the aluminum industry, which the CBSA noted as being derived from GOC laws and policies. The GOC argued that these standards are not legally mandated and enforceable, and further noted that they all relate to the aluminum smelting industry and that the CBSA has not shown any causal link to any measurable price effects in the aluminum extrusions industry.

The GOC further argued that policies that restrict investment and new production capacities should serve to limit supply and have a price increasing effect, if any. The GOC also noted that their industrial policies are "market neutral" (i.e. they will not have any impact on market prices)32 and that they had "allowed increases in costs in the aluminum industry. The intended effect was to slow down overproduction". They further noted that these measures would result in higher costs of production, which would counterbalance the effect of restricting exports.33

CBSA Response

In making its preliminary determination, the CBSA presented the facts surrounding its request for the Industrial Development Policy for the Aluminum Industry and the Special Development Plan for Aluminum Industry Development. The CBSA also presented the GOC's explanations for refusing to provide these two documents. At that time, the CBSA explained that it believed the documents existed and further explained why the documents were requested. The CBSA did not attempt to speculate as to the contents of these two documents that were never provided, nor did the CBSA ever infer that such documents resulted in enforceable measures. 34

For the purposes of the preliminary determination, the CBSA did rely upon numerous GOC circulars, regulations and other measures, provided by the GOC in its section 20 RFI responses, that demonstrate the restrictions, minimum standards and thresholds for the aluminum and aluminum extrusions industries. However, those items did not include the Industrial Development Policy for the Aluminum Industry and the Special Development Plan for Aluminum Industry Development. 35

Regarding the GOC's statement that its industrial policies are "at most aspirational expressions of the GOC's hopes for an industry", the CBSA notes that many of the GOC documents obtained by the CBSA contain very strict wording, including harsh penalties for companies that fail to conform to the written objectives.

-

For example, in the Emergent Circular on Curbing Rebound Investment in the Aluminum Industry, which respects aluminum enterprises that have been using "backward production technology" or are considered "illegal" production facilities according to the industry policy and related regulations, it states rather directly that the government will get the companies "out of the market through stopping supplying power and water." 36 The CBSA is of the opinion that this type of language clearly establishes that the GOC's industrial policies and regulations are much more than aspirational expressions of hope for an industry.

Regarding the market neutrality of GOC industrial policies, the GOC themselves noted that: "macro-economic adjustment policies have also had some influence on the general level of prices"37. As previously noted, they further stated that they have "allowed" cost increases within the industry and, without providing any analysis, stated that these cost increases would fully offset the effect of export restrictions. The GOC, in their own statements and arguments, are therefore acknowledging the effects that their industrial policies and export restrictions can have on determining prices.

The CBSA has considered the cumulative effect that the GOC's measures have exerted on the aluminum extrusions sector in China as part of its "Summary of Findings - Section 20" analysis in Appendix 3 to this Statement of Reasons.

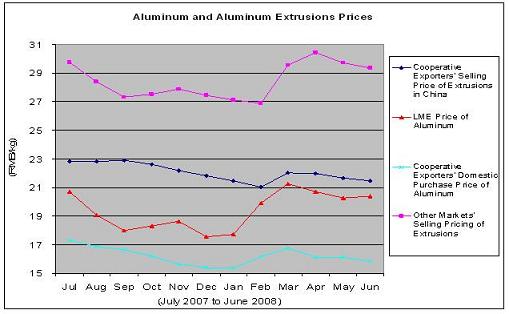

4. Prices of Aluminum in China and on the London Metal Exchange (LME)

The GOC noted that in its preliminary section 20 determination, the CBSA has assumed a 75% aluminum raw material cost on the overall cost of producing aluminum extrusions. The GOC contended this is a "significant overstatement" of the actual proportion, which the GOC understands is closer to 67%. The GOC noted that certain responding producers will be making detailed arguments in this regard and that the CBSA must fully consider this evidence and related arguments in making its final determination. 38

The GOC submitted that the CBSA's section 20 determination based on the factual assumption that prevailing aluminum prices in China are consistently lower than LME prices is wrong and not supported by the evidence on the record. The GOC states that a comparison between the historical data for the monthly prices of aluminum on the Shanghai Nonferrous Metals Market and the LME during 2007 and the first half of 2008 shows that there is an insignificant price divergence of 3.67% on average. The same comparison with historical spot price information from the Ling Tong Metal (LTM) shows an average price divergence of 2.6%. The GOC argued that these figures demonstrate that the spot prices for aluminum in the Chinese markets closely follow LME and world prices. 39

The GOC argued that, in comparing the LME and Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE) prices of aluminum, the CBSA only took into account the alleged price differences without considering the similarities in fluctuations, the influence of the LME over the SHFE, and the difference in the size of both markets. These factors should have been examined and considered before concluding that there is a substantial price difference between aluminum in the "world market" and the SHFE. 40

Pingguo stated that it does not purchase aluminum ingots but molten aluminum, and that the SHFE price for aluminum is sometimes higher than the LME. Pingguo further added that it quotes the LTM price, which is a regional metal market exchange and is generally higher than the Shanghai Futures Exchange price. 41

Pingguo contended that China's pricing in the aluminum sector is a function of supply and demand forces and China's aluminum ingot market prices were actually higher than the LME for half of the POI. Pingguo also submitted that global competition necessarily entails there be variations from one market to the other.

The GOC further submitted that the CBSA failed to consider any local premiums for delivery, or the effects of long term supply contracts for aluminum extrusion producers, both of which the CBSA has information on the record to consider. 42

The GOC argued that even if prices in China were materially lower, that the CBSA cannot simply assume that it is a result of government intervention. The GOC noted that the CBSA must take into consideration all relevant factors that may drive prices in the Chinese market, but the preliminary determination does not disclose "even a perfunctory attempt at such rigour." 43

In its reply submissions, PanAsia stated that there is absolutely no evidence of GOC involvement in any raw material pricing in the aluminum sector. Furthermore, PanAsia, like many other Chinese extruders, does not buy billets but ingots, which it melts into billets. PanAsia also submitted that the CBSA should acknowledge the difference in the methods of production to establish a fair comparison.

With respect to the Complainants' arguments that there is manipulation of prices through taxation policies, Pingguo submitted that this was no different than from taxation policies in Canada. 44 Pingguo submitted that the reasoning in support of the President opinion established at the preliminary determination is weak.

As for difference betweens prices on the LME, the SHFE and the LTM, the Complainants reiterated that the central fact is that the GOC substantially determined pricing of aluminum extrusions in the POI. To this end, the largest part of the reference price (the SHFE price of the ingot), is not the same as in a competitive market (i.e. the LME).

The Complainants alleged that purchasing on the exchange where materials are artificially cheaper, due to the GOC's residency constraints on the SHFE, which is enjoyed exclusively by Chinese producers, allows them to sell goods at below fair market prices. The Complainants indicated that this very fact proves that the SHFE prices are artificially and substantially determined by the GOC and are not the same as in a competitive market. 45

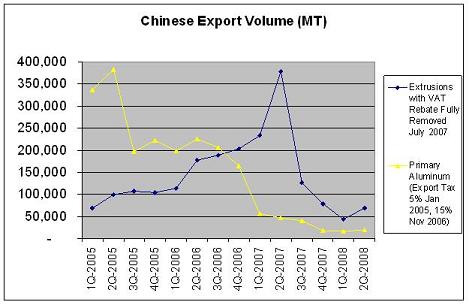

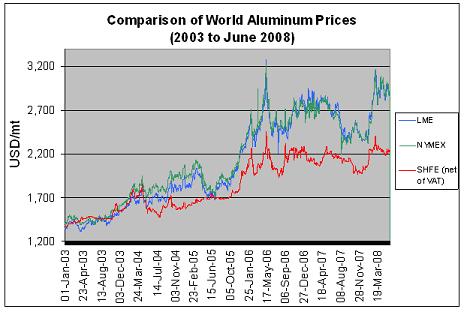

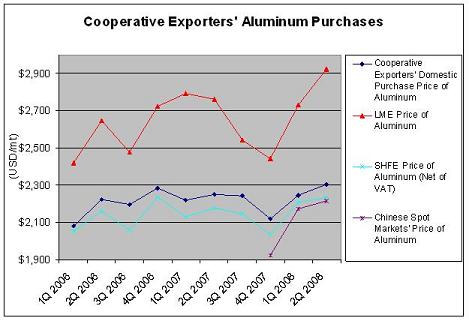

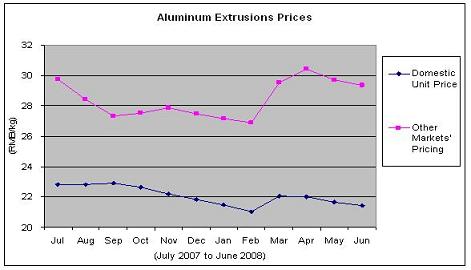

CBSA Response